Lionel Falchero, Florian Guisier, Marie Darrason, Arnaud Boyer, Charles Dayen Sophie Cousin, Patrick Merle, Régine Lamy, Anne Madroszyk, Josiane Otto, Pascale Tomasini, Sandra Assoun, Anthony Canellas, Radj Gervais, José Hureaux, Jacques Le Treut, Olivier Leleu, Charles Naltet, Marie Tiercin, Sylvie Van Hulst, Pascale Missy, Franck Morin, Virginie Westeel, Nicolas Girard

Corresponding author. Nicolas Girard

Institut du Thorax Curie Montsouris, Institut Curie, Paris, France, Paris Saclay University, University Versailles Saint Quentin, Versailles, France.

Highlights

• Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is a highly aggressive type of lung cancer.

•Atezolizumab plus chemotherapy improves overall survival in 1st-line treatment of extensive SCLC.

• IFCT-1905 CLINATEZO studied consecutive patients receiving this regimen in France.

• Our study reproduced in a real-life setting the key survival outcomes of the landmark trial.

Abstract

Background

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) has a tendency towards recurrence and limited survival. Standard-of-care in 1st-line is platinum-etoposide chemotherapy plus atezolizumab or durvalumab, based on landmark clinical trials.

Methods

IFCT-1905 CLINATEZO is a nationwide, non-interventional, retrospective study of patients with extensive SCLC receiving atezolizumab plus chemotherapy as part of the French Early Access Program. The objectives were to analyse effectiveness, safety and subsequent treatments.

Results

The population analyzed included 518 patients who received atezolizumab in 65 participating centers. There were 66.2% male, the mean age was 65.7 years; 89.1% had a performance status (PS) 0/1 and 26.6% had brain metastases. Almost all (95.9%) were smokers. Fifty-five (10.6%) received at least 1 previous treatment. Median number of atezolizumab injections was 7.0 (range [1.0–48.0]) for a median duration of 4.9 months (95% CI 4.5–5.1). Atezolizumab was continued beyond progression in 122 patients (23.6%) for a median duration of 1.9 months (95% CI: [1.4–2.3]). The best objective response was complete and partial in 19 (3.9%) and 378 (77.1%) patients. Stable disease was observed in 50 patients (10.2%). Median follow-up was 30.8 months (95% CI: [29.9 –31.5]). Median overall survival (OS), 12-, 24-month OS rates were 11.3 months (95% CI: [10.1–12.4]), 46.7% (95% CI [42.3–50.9]) and 21.2% (95% CI [17.7–24.8]). Median real-world progression-free survival, 6-, and 12-month rates were 5.2 months (95% CI [5.0 –5.4]), 37.5% (95% CI [33.3–41.7]) and 15.2% (95% CI [12.2–18.6]). For patients with PS 0/1, the median OS was 12.2 months (95% CI [11.0– 13.5]). For patients with previous treatment, the median OS was 14.9 months (95% CI [10.1–21.5]). Three-hundred-and-twenty-six patients (66.4%) received subsequent treatment and 27 (5.2%) were still under atezolizumab at the date of last news.

Conclusions

IFCT-1905 CLINATEZO shows reproductibility, in real-life, of IMpower-133 survival outcomes, possibly attributed to the selection of patients fit for this regimen, adoption of pragmatic approaches, including concurrent radiotherapy and treatment beyond progression.

Keywords

Small cell lung cancer, Chemotherapy, Targeted therapy, Immunotherapy

1. Introduction

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is a highly aggressive type of lung cancer with rapid tumour growth and a tendency toward early recurrence after first-line treatment 1. SCLC accounts for 10– 15% of all newly diagnosed lung cancer cases, and most patients are diagnosed with metastatic, so-called extensive-stage (ES) disease 2,3. While the historical 5-year survival rate for ES-SCLC has been estimated to be <5% with first-line platinum-etoposide chemotherapy 1,2,4, landmark clinical trials recently reported a survival benefit with the addition of anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), including atezolizumab or durvalumab 5,6,7. Especially, the IMpower-133 double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial demonstrated the benefit atezolizumab vs. placebo in combination with carboplatin and etoposide for 4 cycles, followed by a maintenance phase with atezolizumab vs. placebo alone, as first-line therapy in 403 patients with ES-SCLC 5,7. After a median follow-up of 22.9 months, median overall survival (OS) was 12.3 months in the atezolizumab group and 10.3 months in the placebo group (hazard ratio (HR) 0.76; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.60–0.95; p = 0.0154); median progression-free survival (PFS) was 5.2 months and 4.3 months, respectively (HR 0.77; 95% CI 0.63–0.95; p = 0.02). The safety profile of this regimen was consistent with the previously reported safety profile of the individual agents, with no new findings observed. Based on these data, ICIs plus platinum and etoposide regimens are now standard-of-care in ES-SCLC 3,8.

Besides randomized clinical trials in which ES-SCLC patient population may be highly selected, real-world data represent a major piece of knowledge in the clinical decision-making for treatment in SCLC, aiming at providing clinicians with data from special populations not enrolled or analyzed in randomized trials, such as patients with poor general condition or brain metastases that were expected to be treated in the routine practice setting, capturing the actual treatment sequences after immunotherapy, and ultimately assessing the reproducibility of results in patients, especially in the long-term setting. Here we report the results of IFCT-1905 CLINATEZO, a nationwide, non-interventional, retrospective chart review of consecutive patients with ES-SCLC who received atezolizumab plus chemotherapy as part of the French Early Access Program (EAP), that were provided with a unique opportunity to address those objectives.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Study design

IFCT-1905 CLINATEZO is a nationwide, non-interventional, retrospective chart review study of patients with ES-SCLC who received atezolizumab plus chemotherapy as part of the French EAP that ran from May 2019 to March 2020 (1402 patients concerned). Inclusions were exhaustive per participating centers (65 out of the 307). Based on on-site visits, the data collection period ran from March to December 2022 (main data collection plus survival update), by trained French Cooperative Thoracic Intergroup (IFCT) clinical research associates. Atezolizumab (1200 mg flat dosing) was available upon physician request for treatment-naïve patients with ES-SCLC, in combination with carboplatin and etoposide chemotherapy, every 3 weeks. A total of 1402 patients received atezolizumab through this program; requests had to be done through a web platform, and the median time from request to first treatment dose in patients who were treated was 6.3 days. As part of the secondary data use, the present protocol has been made by the compliance commitment to reference method MR-004 submitted to the CNIL (French National Commission for the Protection of Private Data and Rights). This research was registered in the Health Data Hub (HDH) public directory (https://www. health-data-hub.fr/projets) and clinicaltrials.gov database under the ID NCT04920981. The search for the patient’s non-opposition had to be conducted, verbally and in writing (providing the information leaflet), by the physician who followed up with the patient during a consultation. This had to be written in the patient’s medical record. Information about deceased patients may be subject to data processing, except if the concerned patient voiced his refusal while still alive.

2.2 Eligibility criteria

French EAP required patients to fulfil the main inclusion criteria of the landmark IMpower-133 trial 5,7: 1/ pathological or cytological diagnosis of SCLC, 2/extensive stage, i.e. stage IIIB or IV, 3/age of 18 years or older, 4/ life expectancy of at least 3 months, 5/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) of 0 or 1, 6/adequate hematologic, hepatic, and renal function. Exclusion criteria included: 1/treatment with steroids ≥ 10 mg equivalent prednisone in the last 14 days before the initiation of atezolizumab, 2/human immunodeficiency virus infection or known autoimmune disease, except for residual hypothyroidism due to an autoimmune condition, type 1 diabetes mellitus, or psoriasis not requiring systemic treatment, 3/symptomatic or active central nervous system (CNS) metastasis, 4/previous treatment with any immune checkpoint inhibitor, 5/absence of eligibility for an ongoing, recruiting clinical trial. Eligibility was centrally reviewed within the program.

For IFCT-1905 CLINATEZO, selection criteria included: 1/ administration of at least one dose of treatment with atezolizumab and chemotherapy as part of the EAP, 2/ information about the study and acceptance of patients for their data to be collected, 3/ selection period from May 6th 2019 until January 31st 2020 for initiation of treatment with atezolizumab plus chemotherapy to have sufficient follow-up time.

2.3 Study endpoints

Key objectives were to assess the effectiveness and safety of atezolizumab; and analyze subsequent treatment sequences; we also aimed at defining a subset of patients with characteristics similar to that of the IMpower-133 trial, the so-called IMpower-133-like population; outcomes were to be described in special population including patients with brain metastases and PS ≥ 2. Pre-specified endpoints were the following: 1/ Overall Survival (OS), defined as the time from the first dose of treatment with atezolizumab and chemotherapy to death from any cause; 2/ real-world progressi on-free survival (rw-PFS), defined as the time from first dose of treatment with atezolizumab and chemotherapy to first occurrence of disease progression or death from any cause during the study – in this real-life data study, disease progression was assessed by the treating physician, and PFS will be indicative given possible hetero- geneity in the time interval between patients visits at the hospital and tumor radiological assessments, even if imaging assessment using brain, thorax, abdomen computed tomography (CT) scan had – as part of the EAP- to be performed every 6 weeks, and reports sent centrally before continuation of atezolizumab was allowed; these reports were reviewed for this study; 3/ best objective response, recorded from the start of treatment with atezolizumab and chemotherapy until disease progression or start of further anti-cancer treatment; 4/ duration of treatment, defined as the time from first dose of treatment to discontinuation (interruption of more than 2 months) – this included duration of treatment with atezolizumab beyond progression; 5/ pattern of disease progression; 6/ time to subsequent treatment initiation, and information about the type and the duration (time between first dose of treatment and its discontinuation) of systemic therapies administered immediately after atezolizumab and chemotherapy – local treatment during or immediately after treatment with atezolizumab and chemotherapy was also recorded; 7/ safety profile adverse events (AEs) were collected from medical record of the patient after onsite review by research study assistants from IFCT. With this methodology, maximal grade 3-4-5 treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) were systematically recorded, and graded according to National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0.

2.4 Collection of data

Clinical data from 518 patients enrolled in the EAP were collected from medical records at 65 investigator sites, by research study assistants working at the IFCT, using a dedicated case report form. The expected precision according to the sample size of this data-driven analysis is based on the results of IMpower-133 5,7, to obtain an acceptable precision for 6-month OS; with the above information, the inclusion of at least 500 patients was allowing a precision of<5% in the 6 months OS. The data collection period ranges from March to December 2022. Besides study endpoints, a total of 206 variables were collected, including the above-mentioned eligibility criteria, patients’ characteristics – performance status, auto-immune and paraneoplastic disorders, smoking history -, sites of metastases at baseline and disease progression, and reason for discontinuation of treatments.

2.5 Statistical analyses

Database lock was done on July 25th 2022. The cut-off date (i.e. date beyond which events were no longer taken into account in the survival analysis) was set on June 1st, 2022.

Quantitative variables were described by the number of values entered, the number of missing data, the mean, the standard deviation, the median, the 1st and the 3rd quartile. Qualitative variables were described by the number of values entered, the number of missing values, the frequency and the percentage per category. If relevant, the 95% confidence interval was calculated. The alpha risk was fixed at 5%, two-sided. OS and rw-PFS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test was used for survival comparisons. A univariate proportional hazards regression model was used to test the association of each factor with rw-PFS and OS (the proportional hazards assumption was tested), and then a multivariate model with a stepwise selection including all factors was applied to identify the independent prognostic roles of patient characteristics. Statistical analyses were computed with SAS 9.4 software.

3. Results

3.1 Patient population and characteristics

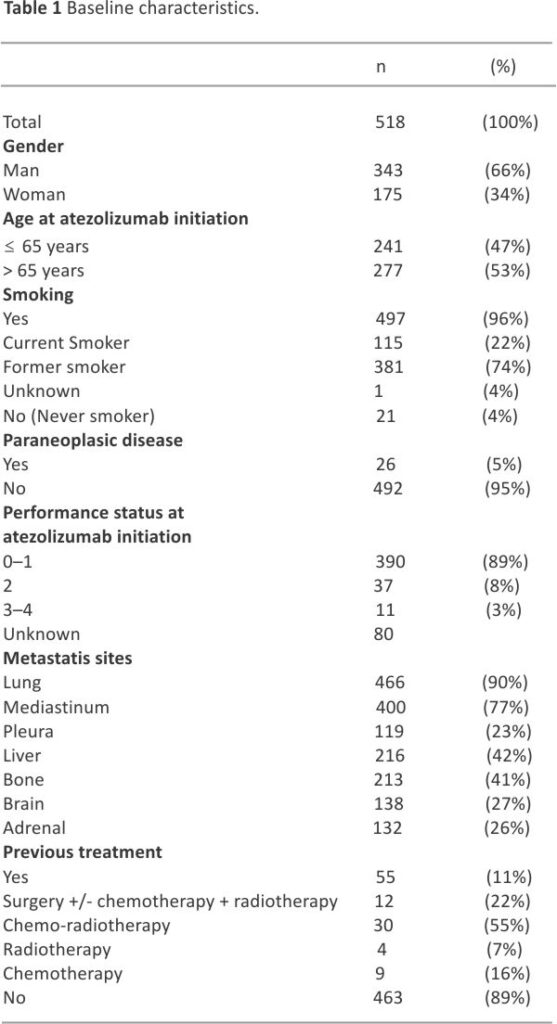

ITT population included a total of 518 patients, of which 491 had discontinued atezolizumab at the cut-off date and for whom 326 (66.4%) did receive subsequent treatment. As shown in Table 1, a majority of patients were male (66.2%) and more than half were above 65 years of age (53.5%); the mean age was 65.7 years (range: 36.7–88.0). A total of 55 (10.6%) patients had received previous therapy for limited-stage SCLC (n = 46) or ES-SCLC (n = 9). Almost all (95.9%) patients had a tobacco-smoking history, with current and former smokers at 22.2% and 73.7% respectively. The median number of pack years was 40.0 (range: 5.0–150). Most patients (89.1%) had a performance status (PS) of 0–1, and 26.6% had baseline brain metastases.

3.2 Atezolizumab treatment

All but 2 patients received carboplatin and etoposide regimens in combination with atezolizumab; the 2 other patients received cisplatin and paclitaxel respectively. Median number of chemotherapy cycles was 4.0 (range:1.0–9.0). Median number of atezolizumab injections was 7.0 (range:1.0–48.0), for a median time of 4.9 (95% CI 4.5–5.1) months. Concurrent radiotherapy was administered on brain metastases in 28 (5.4%) patients, on other sites in 101 (19.5%) patients – lung in 25 (4.8%) patients, mediastinum in 23 (4.4%) patients, bone metastases in 28 (5.4%) patients; 9 (1.7%) patients had surgery of bone, brain, or digestive tract metastases. In addition, 67 (12.9%) patients had prophylactic brain irradiation.

Atezolizumab was continued beyond disease progression in 122 (23.6%), for a median duration of 1.9 (95% CI 1.4–2.3) months; 42 (8%) of these patients had radiotherapy on progressive lesions. At data cut-off, 491 (95.0%) patients had discontinued atezolizumab, because of disease progression in 385 (78.4%), toxicity in 34 (6.9%) patients, death in 29 (5.9%) patients, and patient refusal, intercurrent event, second cancer, loss of follow-up and other reason – in 43 (8.3%).

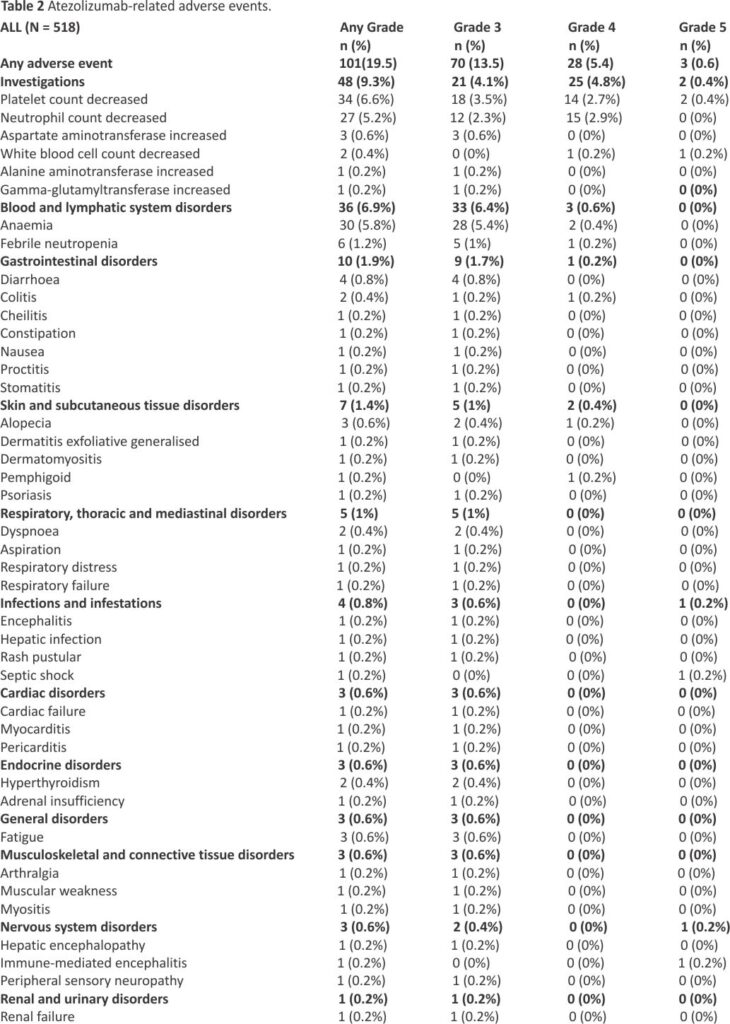

Atezolizumab-related adverse events are presented in Table 2; grade ≥ 3 events were reported in 101 (19.5%) patients. Grade ≥ 3 events were not higher in patients who received radiotherapy during treatment with atezolizumab.

3.3 Response and Progression

The best objective response was reported as a complete response in 19 (3.9%) patients, partial response in 378 (77.1%) patients, and stable disease in 50 (10.2%) patients; progressive disease was observed in 43 (8.8%) patients. Disease control was observed in 447 (91.2%) patients.

Ultimately, at the data cut-off, 430 (83.0%) patients had shown disease progression. Sites included the brain in 149 (34.6%) patients, the mediastinum in 147 (34.2%) patients, the liver in 97 (22.6%) patients, and the bone in 64 (14.9%) patients.

3.4 Outcomes

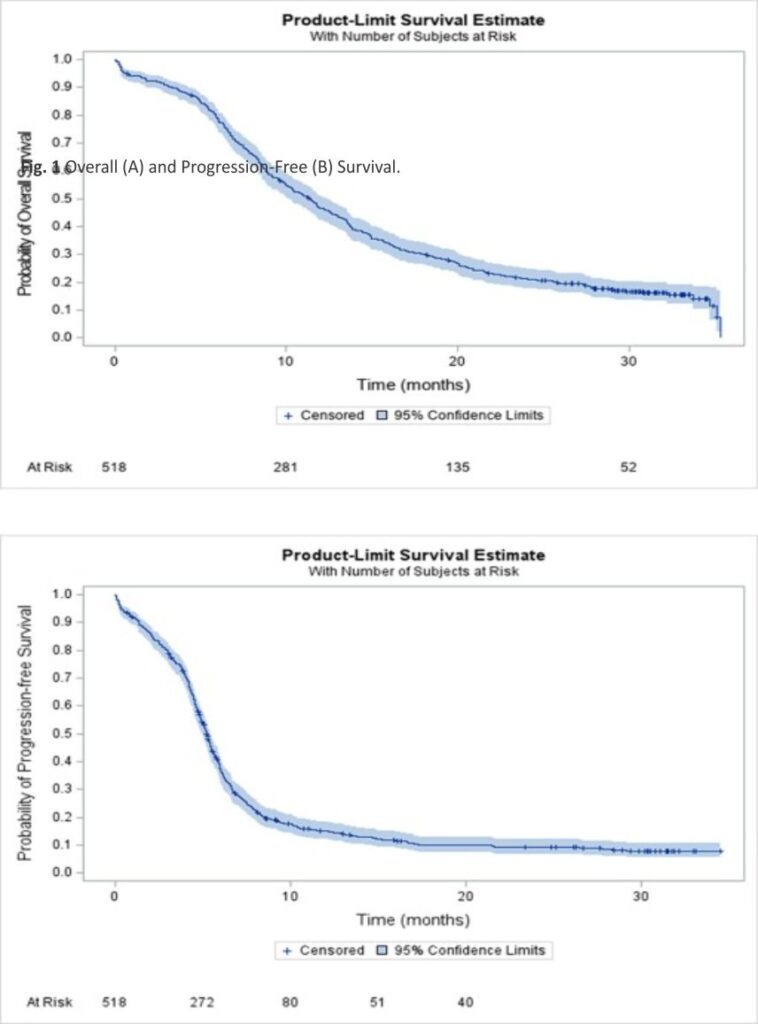

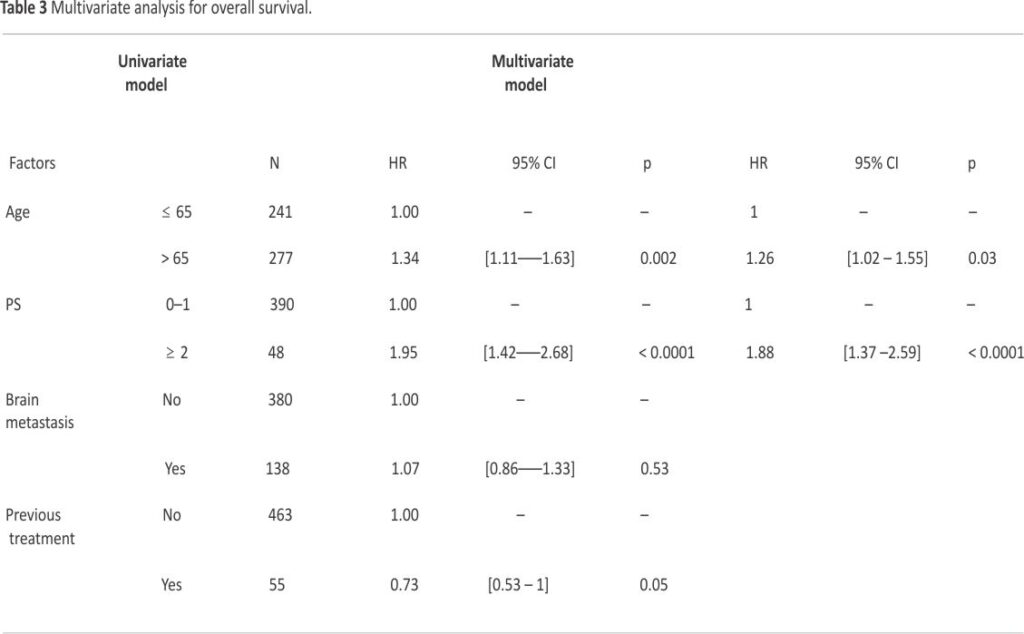

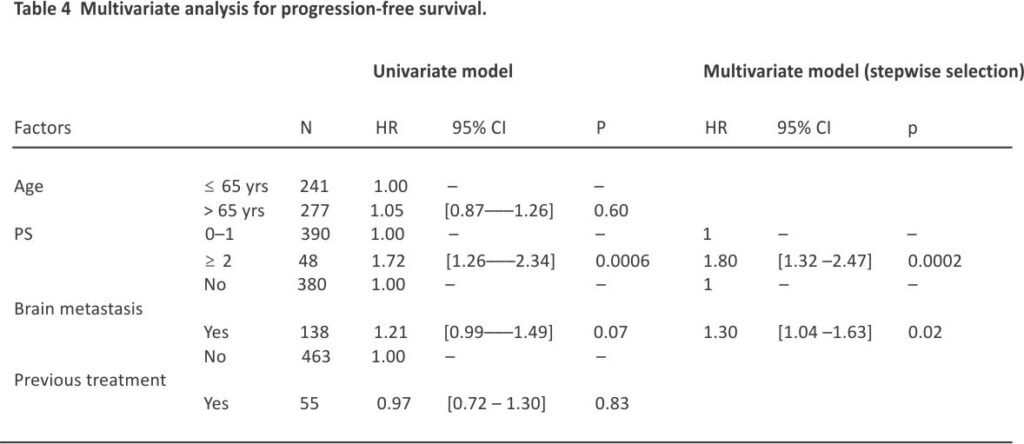

After a median follow-up of 30.8 (95% CI 29.9–31.5) months, median, 12- and 24-month OS rate in the ITT population were 11.3 (95% CI 10.1–12.4) months, 46.7% (95% CI 42.3–50.9), and 21.2% (95% CI 17.7–24.8), respectively (Fig. 1A). Median, 6- and 12-month rw-PFS rate was 5.2 (95% CI 5.0–5.4) months, 37.5% (95% CI 33.3–41.7) and 15.2% (95% CI 12.2–18.6), respectively (Fig. 1B). In the IMpower-133-like patient population with PS 0–1, median OS and rw-PFS were 11.9 (95% CI 10.7–13.5) and 5.3 (95% CI 5.1–5.7) months, respectively (Supplemental Table 1). At multivariate analysis, OS was not different in patients with or without baseline brain metastases (median of 9.9 (95% CI 8.0–12.5) and 11.6 (95% CI 10.4–13.0) months, respectively (p = NS). Age was a prognostic factor with median OS in patients ≤ 65 years and greater than 65 years corresponding to 13.2 (95% CI 11.4–14.4) and 9.8 (95% CI 8.8–11.3) months respectively (HR = 1.26 (95% CI 1.02–1.55, p = 0.03) (Table 3). The performance status was also a prognostic factor with median OS in patients with PS 0–1 and PS ≥ 2 corresponding to 12.2 (95% CI 11.0–13.5) and 6.3 (95% CI 4.5– 9.2) months respectively (HR = 1.88 (95% CI 1.4–2.6) p < 0.001). For PFS, the performance status and brain metastasis were prognostic factors with HR = 1.80 (95% CI 1.3–2.5) p = 0.0002 and HR = 1.30 (95% CI 1.0 –1.6) p = 0.02 respectively (Table 4).

3.5 Subsequent therapies

A total of 326 patients, among the 491 who discontinued the treatment, received subsequent therapy after atezolizumab (66.4%), consisting of chemotherapy in 235 (72.1%) patients, chemo-radiotherapy in 69 (21.2%) patients, and radiotherapy alone in 22 (6.7%) patients- in the setting of oligoprogressive disease. Chemotherapy regimens included carboplatin and etoposide for 98 (32.2%) patients – combined with atezolizumab in 4 (1.3%) patients, carboplatin and paclitaxel in 32 (10.5%) patients, topotecan in 72 (23.7%) patients, or other single-agent cytotoxic agents in 81 (27%). Two patients received EGFR inhibitors combined with chemotherapy. The objective response rate was 41.6%, and stable disease rate was 25.8%. The response rate was significantly higher in patients who received platinum and etoposide vs. other second-line therapies (62.6% vs. 30.7%, p < 0.001). The median duration of the first subsequent therapy was 2.1 (95% CI 1.8–2.3) months.

4. Discussion

IFCT-1905 CLINATEZO is, to our knowledge, one of the largest cohorts of patients with ES-SCLC who received atezolizumab plus chemotherapy in first-line treatment. Taken together, our results indicate 1/ the reproducibility in a real-life setting, of the key survival outcomes of the landmark IMpower-133 trial, which may be related to a selection of patients fit for this regimen, 2/ the adoption of pragmatic approaches for the management of patients receiving atezolizumab, that includes concurrent radiotherapy and treatment beyond progression, and 3/ the high access to second-line therapies, mostly based on chemotherapy.

IFCT 1905-CLINATEZO demonstrates the reproducibility of the landmark effectiveness outcomes of atezolizumab combined with chemotherapy in first-line treatment of ES-SCLC, as demonstrated in the landmark IMpower-133 randomized trial, with median rw-PFS and OS of 5.2 and 11.3 months, vs. 5.3 and 12.3 months, respectively 5,7, and 12-month OS of 51.7% and 46.7%, respectively (Supplemental Table 1) 7. In the IFCT-1905 CLINATEZO versus IMpower-133 trial, there were more patients with poor PS (11% versus none) and more cerebral metastases (27% versus 8%). In other, more limited real-world cohorts, similar outcomes were reported. The Italian MAURIS study enrolled 155 patients, with similar baseline characteristics to IFCT-1905 CLINATEZO, and median rw-PFS and OS of 5.5 (95 %CI 5.3–5.8) months and 10.7 (95% CI 9.9–13.7) months 9. IMfirst is a phase IIIb prospective, open-label trial of 155 patients who received atezolizumab combined with platinum and etoposide combination, with the possible enrolment of patients with PS 2, and/or untreated, stable brain metastases, and/or autoimmune disorders; PFS and OS were 6.2 (95 %CI 5.8–6.4) and 10.0 (95 %CI 8.6–11,9) months 10. Other cohorts 11, as well as some with durvalumab immunotherapy 12, based on the CASPIAN regimen 6, reported similar results.

Meanwhile, the significant heterogeneity of patient baseline characteristics in those studies may question the value of such comparisons; indeed, several real-world studies in ES-SCLC reported similar OS – ranging from 7.0 to 14.0 months – without the addition of immunotherapy to platinum and etoposide chemotherapy 13, 14,15. Meanwhile, results from a French cohort of patients who did not receive immunotherapy recently reported median rw-PFS of 6.2 and 6.1 months, and OS of 13.2 months and 11.8 months for cisplatin/ etoposide and carboplatin/ etoposide doublet regimens, respectively 16.

Interestingly, in IFCT-1905 CLINATEZO, the majority of patients had a PS 0–1 and nearly half were < 65 years old; in real-world cohorts, a higher proportion of patients were elderly, or had co-morbidities and poorer general conditions 13,14,15. It has been estimated that only one-third of patients are eligible for immunotherapy 17. Still, an unmet need remains the identification of patients benefiting, in terms of long-term outcomes, from this regimen; in that matter, molecular signatures have shown some promise, with a correlation between the so-called SCLC-I subtype and survival 5.

IFCT-1905 CLINATEZO provides unique insight into the practical management of immunotherapy with atezolizumab in the first-line treatment of ES-SCLC. Our study shows that this IMpower-133 regimen has been used for 55 (11%) patients in the setting of platinum and etoposide rechallenge in ES-SCLC platinum-sensitive cases or after recurrence after definitive chemo-radiotherapy for limited-stage disease; OS, not rw-PFS, was numerically higher – the median of 14.9 months (95% CI 10.1–21.5) – in this setting. While it is standard to rechallenge patients with chemo-therapy 18, the benefit of immuno-therapy in such a situation was not formally assessed; only 4% of such patients were not enrolled in the IMpower-133 trial 5. Second, many patients did receive radiotherapy concurrently with atezolizumab (19.5%), including brain radiotherapy in 5% of patients. Interestingly, baseline brain metastases did not significantly impact outcomes in our cohort, which may be related to a selection of asymptomatic, stable cases, as well as to the delivery of radiotherapy, that was previously reported to be safe 19. Third, while radiotherapy may have been administered upfront, IFCT-1905 CLINATEZO shows that a high proportion −24%- of patients were treated with atezolizumab beyond progression, for a median duration of 1.9 (95% CI [1.4–2.3]) months, possibly in the setting of focal treatment of oligoprogressive disease, found in 42 (8%) patients who continued atezolizumab post-progression, and 22 (4%) patients who discontinued atezolizumab, a strategy adopted in clinical practice in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), treated with immunotherapy or targeted agents 20,21.

In IFCT-1905 CLINATEZO, sites of disease progression after atezolizumab included the brain and/or the mediastinum in more than one-third of patients. This raises the question of the administration of prophylactic brain irradiation (PCI) in the 4% of patients achieving a complete response, as reported previously 22, and/or consolidation radiotherapy on mediastinal oligo residual disease, such as in the randomized, phase III CREST trial 23, that both demonstrated some benefit. Thoracic radiotherapy, as well as prophylactic brain radiotherapy, is considered optional in the most recent current guidelines for the treatment of ES-SCLC, for patients not receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors 8; indeed, thoracic radiotherapy was not part of landmark clinical trials with immunotherapy, as sequencing with maintenance remains complex; PCI was authorized in the CASPIAN trial, with no reported data so far.

Ultimately, IFCT-1905 CLINATEZO shows that a majority of patients – 326 cases (63%) – were eligible for second-line therapy after atezolizumab; a total of 98 (32%) patients did receive platinum and etoposide regimens as second-line, suggesting these were platinum-sensitive cases. Interestingly, atezolizumab was discontinued in all these patients, which may be questioned as the mechanism of resistance is historically understood as being related to a reduction of the cytotoxic effect of chemotherapy, not a truly acquired resistance to immunotherapy; continuation of immunotherapy in the setting of initiation of second-line chemotherapy was shown to produce significant response rates, PFS and OS in NSCLC 24. Our study indicates, beyond platinum-sensitive cases, the major unmet need for active options after the failure of atezolizumab plus chemotherapy, as the median duration of the first subsequent therapy was 2.1 (95% CI [1.8–2.3]) months.

In conclusion, IFCT-1905 CLINATEZO shows the reproductibility in a real-life setting, of the key survival outcomes of IMpower-133, which may be related to a selection of patients fit for this regimen, the adoption of pragmatic approaches for the management of patients receiving atezolizumab, that includes concurrent radiotherapy and treatment beyond progression, and the high access to second-line therapies, mostly based on chemotherapy, with limited outcomes.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank the CLINATEZO contributors, listed here who collaborated on this project and provided data for 1 patient or more, (not included in the list of authors):

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04920981.

Funding.

This work was supported by an unrestricted grant from Hoffmann-LaRoche. The funding source had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or preparation of this manuscript.

References

1. Gazdar A.F., Bunn P.A., Minna J.D. Small-cell lung cancer: what we know, what we need to know and the path forward. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2017; 17: 725-737

2. Nicholson A.G., Chansky K., Crowley J., Beyruti R., Kubota K., Turrisi A., Eberhardt W.E.E., van Meerbeeck J., Rami-Porta R., Goldstraw P., Rami-Porta R., Asamura H., Ball D., Beer D.G., Beyruti R., Bolejack V., Chansky K., Crowley J., Detterbeck F., Erich Eberhardt W.E., Edwards J., Galateau-Sallé F., Giroux D., Gleeson F., Groome P., Huang J., Kennedy C., Kim J., Kim Y.T., Kingsbury L., Kondo H., Krasnik M., Kubota K., Lerut T., Lyons G., Marino M., Marom E.M., van Meerbeeck J., Mitchell A., Nakano T., Nicholson A.G., Nowak A., Peake M., Rice T., Rosenzweig K., Ruffini E., Rusch V., Saijo N., Van Schil P., Sculier J.-P., Shemanski L., Stratton K., Suzuki K., Tachimori Y., Thomas C.F., Travis W., Tsao M.S., Turrisi A., Vansteenkiste J., Watanabe H., Wu Y.-L., Baas P., Erasmus J., Hasegawa S., Inai K., Kernstine K., Kindler H., Krug L., Nackaerts K., Pass H., Rice D., Falkson C., Filosso P.L., Giaccone G., Kondo K., Lucchi M., Okumura M., Blackstone E., Cavaco F.A., Barrera E.A., Arca J.A., Lamelas I.P., Obrer A.A., Jorge R.G., Ball D., Bascom G.K., Blanco Orozco A.I., González Castro M.A., Blum M.G., Chimondeguy D., Cvijanovic V., Defranchi S., de Olaiz Navarro B., Escobar Campuzano I., Vidueira I.M., Araujo E.F., García F.A., Fong K.M., Corral G.F., González S.C., Gilart J.F., Arangüena L.G., Barajas S.G., Girard P., Goksel T., González Budiño M.T., González Casaurrán G., Gullón Blanco J.A., Hernández Hernández J., Rodríguez H.H., Collantes J.H., Heras M.I., Izquierdo Elena J.M., Jakobsen E., Kostas S., Atance P.L., Ares A.N., Liao M., Losanovscky M., Lyons G., Magaroles R., De Esteban Júlvez L., Gorospe M.M., McCaughan B., Kennedy C., Melchor Íñiguez R., Miravet Sorribes L., Naranjo Gozalo S., de Arriba C.Á., Núñez Delgado M., Alarcón J.P., Peñalver Cuesta J.C., Park J.S., Pass H., Pavón Fernández M.J., Rosenberg M., Rusch V., de Cos Escuín J.S., Vinuesa A.S., Serra Mitjans M., Strand T.E., Subotic D., Swisher S., Terra R., Thomas C., Tournoy K., Van Schil P., Velasquez M., Wu Y.L., Yokoi K. The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for the Revision of the Clinical and Pathologic Staging of Small Cell Lung Cancer in the Forthcoming Eighth Edition of the TNM Classification for Lung Cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2016; 11: 300-311

3. Dingemans A.-M.-C., Früh M., Ardizzoni A., Besse B., Faivre-Finn C., Hendriks L.E., Lantuejoul S., Peters S., Reguart N., Rudin C.M., De Ruysscher D., Van Schil P.E., Vansteenkiste J., Reck M. ESMO Guidelines Committee. Small-cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2021; 32: 839-853

4. Wang S., Tang J., Sun T., Zheng X., Li J., Sun H., Zhou X., Zhou C., Zhang H., Cheng Z., Ma H., Sun H. Survival changes in patients with small cell lung cancer and disparities between different sexes, socioeconomic statuses and ages.

5. Horn L., Mansfield A.S., Szczęsna A., Havel L., Krzakowski M., Hochmair M.J., Huemer F., Losonczy G., Johnson M.L., Nishio M., Reck M., Mok T., Lam S., Shames D.S., Liu J., Ding B., Lopez-Chavez A., Kabbinavar F., Lin W., Sandler A., Liu S.V. First-line Atezolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Extensive-Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018; 379: 2220-2229

6. Goldman J.W., Dvorkin M.,Chen Y., Reinmuth N., Hotta K., Trukhin D., Statsenko G., Hochmair M.J., Özgüroğlu M., Ji J.H., Garassino M.C., Voitko O., Poltoratskiy A., Ponce S., Verderame F., Havel L., Bondarenko I., Każarnowicz A., Losonczy G., Conev N.V., Armstrong J., Byrne N., Thiyagarajah P., Jiang H., Paz-Ares L., Dvorkin M., Trukhin D., Statsenko G., Voitko N., Poltoratskiy A., Bondarenko I., Chen Y., Kazarnowicz A., Paz-Ares L., Özgüroglu M., Conev N., Hochmair M., Burghuber O., Havel L., Çiçin I., Losonczy G., Moiseenko V., Erman M., Kowalski D., Wojtukiewicz M., Adamchuk H., Vasilyev A., Shevnia S., Valev S., Reinmuth N., Ji J.H., Insa Molla M.A., Ursol G., Chiang A., Hartl S., Horváth Z., Pajkos G., Verderame F., Hotta K., Kim S.-W., Smolin A., Göksel T., Dakhil S., Roubec J., Bogos K., Garassino M.C., Cornelissen R., Lee J.-S., Garcia Campelo M.R., Lopez Brea M., Alacacioglu A., Casarini I., Ilieva R., Tonev I., Somfay A., Bar J., Zer Kuch A., Minelli M., Bartolucci R., Roila F., Saito H., Azuma K., Lee G.-W., Luft A., Urda M., Delgado Mingorance J.I., Majem Tarruella M., Spigel D., Koynov K., Zemanova M., Panse J., Schulz C., Pápai Székely Z., Sárosi V., Delmonte A., Bettini A.C., Nishio M., Okamoto I., Hendriks L., Mandziuk S., Lee Y.G., Vladimirova L., Isla Casado D., Domine Gomez M., Navarro Mendivil A., Morán Bueno T., Wu S.-Y., Knoble J., Skrickova J., Venkova V., Hilgers W., Laack E., Bischoff H., Fülöp A., Laczó I., Kósa J., Telekes A., Yoshida T., Kanda S., Hida T., Hayashi H., Maeda T., Kawamura T., Nakahara Y., Claessens N., Lee K.H., Chiu C.-H., Lin S.-H., Li C.-T., Demirkazik A., Schaefer E., Nikolinakos P., Schneider J., Babu S., Lamprecht B., Studnicka M., Fausto Nino Gorini C., Kultan J., Kolek V., Souquet P.-J., Moro-Sibilot D., Gottfried M., Smit E., Lee K.H., Kasan P., Chovanec J., Goloborodko O., Kolesnik O., Ostapenko Y., Lakhanpal S., Haque B., Chua W., Stilwill J., Sena S.N., Girotto G.C., De Marchi P.R.M., Martinelli de Oliveira F.A., Dos Reis P., Krasteva R., Zhao Y., Chen C., Koubkova L., Robinet G., Chouaid C., Grohe C., Alt J., Csánky E., Somogyiné Ezer É., Heching N.I., Kim Y.H., Aatagi S., Kuyama S., Harada D., Nogami N., Nokihara H. Goto H., Staal van den Brekel A., Cho E.K., Kim J.-H., Ganea D., Ciuleanu T., Popova E., Sakaeva D., Stresko M., Demo P., Godal R., Wei Y.-F., Chen Y.-H., Hsia T.-C., Lee K.-Y., Chang H.-C., Wang C.-C., Dowlati A., Sumey C., Powell S., Goldman J., Zarba J.J., Batagelj E., Pastor A.V., Zukin M., Baldotto C.S.d.R., Schlittler L.A., Calabrich A., Sette C., Dudov A., Zhou C., Lena H., Lang S., Pápai Z., Goto K., Umemura S., Kanazawa K., Hara Y.u., Shinoda M., Morise M., Hiltermann J., Mróz R., Ungureanu A., Andrasina I., Chang G.-C., Vynnychenko I., Shparyk Y., Kryzhanivska A.,Ross H., Mi K., Jamil R., Williamson M., Spahr J., Han Z., Wang M., Yang Z., Hu J., Li W., Zhao J., Feng J., Ma S., Zhou X., Liang Z., Hu Y.i., Chen Y., Bi M., Shu Y., Nan K., Zhou J., Zhang W., Ma R., Yang N., Lin Z., Wu G., Fang J., Zhang H., Wang K., Chen Z. Durvalumab, with or without tremelimumab, plus platinum-etoposide versus platinum-etoposide alone in first-line treatment of extensive stage small-cell lung cancer (CASPIAN): updated results from a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021; 22: 51-65

7. Liu S.V., Reck M., Mansfield A.S., Mok T., Scherpereel A., Reinmuth N., Garassino M.C., De Castro Carpeno J., Califano R., Nishio M., Orlandi F., Alatorre-Alexander J., Leal T., Cheng Y., Lee J.-S., Lam S., McCleland M., Deng Y.u., Phan S., Horn L. Updated Overall Survival and PD-L1 Subgroup Analysis of Patients With Extensive-Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer Treated With Atezolizumab, Carboplatin, and Etoposide (IMpower-133). J. Clin. Oncol. 2021; 39: 619-630

8. https://www.nccn.org/prof essionals/physician_gls/pdf/ sclc.pdf.

9. Bria E., Garassino M.C., Del Signore E., Morgillo F., Spinnato F., Morabito A., Iero M., Ardizzoni A. 1533P – Atezolizumab (ATZ) plus carboplatin (Cb) and etoposide (eto) in patients with untreated extensive-stage small cell lung cancer (ES-SCLC): Results from the interim analysis of MAURIS trial. Ann. Oncol. 2022; 33: S1248

10. Isla D., Arriola E., Garcia Campelo M.R., Diz Tain P., Marti Blanco C., Lopez-Brea Piqueras M.M., Moreno Vega A.L., Leon Mateos L.A., Oramas Rodriguez J.M., Gutierrez Calderon V., Majem Tarruella M., Sanchez Hernandez A., Aguado de la Rosa C., Alvarez Cabellos R., Marti Ciriquian J.L., Moreno Paul A., Firvida Perez J.L., Callejo Mellén Á., Baez L., Paz-Ares L., 1532P – Phase IIIb study of durvalumab plus platinum-etoposide in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small cell lung cancer (CANTABRICO): Preliminary efficacy results. Ann. Oncol. 2022; 33: S1247-S1248

11. Estrin A., Wang X., Boccuti A., Prince P., Gautam N., Rengarajan B., Li W., Lu T., Cao Y., Naveh N., D’Agostino R., Ben-Joseph R., Ganti A.K. 1539P – Real world (RW) outcomes of second-line (2L) small cell lung cancer (SCLC) patients treated with lurbinectedin. Ann. Oncol. 2022; 33: S1250

12. Chen H., Ma X., Liu J., Yang Y.u., Fang Y., Wang L., Fang J., Zhao J., Zhuo M. Clinical outcomes of atezolizumab in combination with etoposide/platinum for treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: A real-world, multicenter, retrospective, controlled study in China. Chin. J. Cancer Res. 2022; 34: 353-364

13. Hermes A., Waschki B., Gatzemeier U., Reck M. Characteristics, treatment patterns and outcomes of patients with small cell lung cancer–a retrospective single institution analysis. Lung Cancer. 2011; 71: 363-366

14. Huang L.L., Hu X.S., Wang Y., Li J.L., Wang H.Y., Liu P. et al. Survival and pretreatment prognostic factors for extensive-stage small cell lung cancer: A comprehensive analysis of 358 patients. Thorac Cancer. 2021; 12: 1943-1951

15. Tendler S., Zhan Y., Pettersson A., Lewensohn R., Viktorsson K., Fang F., De Petris L. Treatment patterns and survival outcomes for small-cell lung cancer patients – a Swedish single-centre cohort study. Acta Oncol. 2020; 59: 388-394

16. Valette C.A., Filleron T., Debieuvre D., Lena H., Pérol M., Chouaid C., Simon G., Quantin X., Girard N. Treatment patterns and clinical outcomes of extensive stage small cell lung cancer (SCLC) in the real-world evidence ESME cohort before the era of immunotherapy. Respir Med Res. 2023; 84: 101012

17. Rittberg R., Leung B., Al-Hashami Z., Ho C. Real-world eligibility for platinum doublet plus immune checkpoint inhibitors in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer. Front. Oncol. 2022; 12: 1002385

18. Baize N., Monnet I., Greillier L., Geier M., Lena H., Janicot H., Vergnenegre A., Crequit J., Lamy R., Auliac J.-B., Letreut J., Le Caer H., Gervais R., Dansin E., Madroszyk A., Renault P.-A., Le Garff G., Falchero L., Berard H., Schott R., Saulnier P., Chouaid C. Carboplatin plus etoposide versus topotecan as second-line treatment for patients with sensitive relapsed small-cell lung cancer: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020; 21: 1224-1233

19. Ma J.i., Tian Y., Hao S., Zheng L., Hu W., Zhai X., Meng D., Zhu H. Outcomes of first-line anti-PD-L1 blockades combined with brain radiotherapy for extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer with brain metastasis. J. Neurooncol. 2022; 159: 685-693

20. Molinier O., Besse B., Barlesi F., Audigier-Valette C., Friard S., Monnet I., Jeannin G., Mazières J., Cadranel J., Hureaux J., Hilgers W., Quoix E., Coudert B., Moro-Sibilot D.,Fauchon E., Westeel V., Brun P., Langlais A., Morin F., Souquet P.J., Girard N. IFCT-1502 CLINIVO: real-world evidence of long-term survival with nivolumab in a nationwide cohort of patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer.

21. Franceschini D., De Rose F., Cozzi S., Franzese C., Rossi S., Finocchiaro G., Toschi L., Santoro A., Scorsetti M. The use of radiation therapy for oligoprogressive/oligopersistent oncogene-driven non-small cell lung cancer: State of the art. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2020; 148: 102894

22. Yu N.Y., Sio T.T., Ernani V., Savvides P., Schild S.E. Role of Prophylactic Cranial Irradiation in Extensive-Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2021; 19: 1465-1469

23. Slotman B.J., Faivre-Finn C., van Tinteren H., Keijser A., Praag J., Knegjens J., Hatton M., van Dam I., van der Leest A., Reymen B., Stigt J., Haslett K., Tripathi D., Smit E.F., Senan S. Which patients with ES-SCLC are most likely to benefit from more aggressive radiotherapy: A secondary analysis of the Phase III CREST trial. Lung Cancer. 2017; 108: 150-153

24. Özgüroğlu M., Kilickap S., Sezer A., Gumus M., Bondarenko I., Gogishvili M., Nechaeva M., Schenker M., Cicin I., Ho G.F., Kulyaba Y., Dvorkin M., Zyuhal K., Scheusan R.I., Li S., Pouliot J.-F., Seebach F., Lowy I., Gullo G., Rietschel P. LBA54 – Three years survival outcome and continued cemiplimab (CEMI) beyond progression with the addition of chemotherapy (chemo) for patients (pts) with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): The EMPOWER-Lung 1 trial. Ann. Oncol. 2022; 33: S1421

CREDITS: Falchero L, Guisier F, Darrason M, Boyer A, Dayen C, Cousin S, Merle P, Lamy R, Madroszyk A, Otto J, Tomasini P, Assoun S, Canellas A, Gervais R, Hureaux J, Le Treut J, Leleu O, Naltet C, Tiercin M, Van Hulst S, Missy P, Morin F, Westeel V, Girard N. Long-term effectiveness and treatment sequences in patients with extensive stage small cell lung cancer receiving atezolizumab plus chemotherapy: Results of the IFCT-1905 CLINATEZO real-world study. DOI:https://doi. org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2023.107379