Prof Rafael Pérez-Escamilla PhDa, Cecília Tomori PhDb, Sonia Hernández-Cordero PhDc, Phillip Baker PhDd, Aluisio J D Barros PhD MDe, France Bégin PhDf, Donna J Chapman PhDg, Laurence M Grummer-Strawn PhDi, Prof David McCoy PhDj, Purnima Menon PhDk, Paulo Augusto Ribeiro Neves PhDe, Ellen Piwoz PhDl, Prof Nigel Rollins MDh, Prof Cesar G Victora PhD, MDe, Prof Linda Richter PhDm on behalf of the 2023 Lancet Breastfeeding Series Group†

Summary

In this Series paper, we examine how mother and baby attributes at the individual level interact with breastfeeding determinants at other levels, how these interactions drive breastfeeding outcomes, and what policies and interventions are necessary to achieve optimal breastfeeding. About one in three neonates in low-income and middle-income countries receive pre lacteal feeds, and only one in two neonates are put to the breast within the first hour of life. Prelacteal feeds are strongly associated with delayed initiation of breastfeeding. Self-reported insufficient milk continues to be one of the most common reasons for introducing commercial milk formula (CMF) and stopping breastfeeding. Parents and health professionals frequently misinterpret typical, unsettled baby behaviours as signs of milk insufficiency or inadequacy. In our market-driven world and in violation of the WHO International Code for Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes, the CMF industry exploits the concerns of parents about these behaviours with unfounded product claims and advertising messages. A synthesis of reviews between 2016 and 2021 and country-based case studies indicate that breastfeeding practices at a population level can be improved rapidly through multilevel and multicomponent interventions across the socioecological model and settings. Breastfeeding is not the sole responsibility of women and requires collective societal approaches that take gender inequities into consideration.

Introduction

Human infants (aged ≤12 months) and young children (aged 12–36 months) are most likely to survive, grow, and develop to their full potential when fed human milk from their mothers through breastfeeding1 due to the dynamic and interactional nature of breastfeeding and the unique living properties of breastmilk.2,3 Breastfeeding promotes healthy brain development and is essential for preventing the triple burden of malnutrition, infectious diseases, and mortality, while also reducing the risk of obesity and chronic diseases in later life in low-income and high-income countries alike.1,4,5 Breastfeeding supports birth spacing because when the baby nurses from the breast the mother’s body releases hormones that prevent ovulation, leading to lactational amenorrhoea.1,6 Breastfeeding also helps to protect the mother against chronic diseases, including breast and ovarian cancers, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.1,6 The substantial, positive, early-life effects of breastfeeding for children, mothers, families, and wider society are sustained over the life course7 with strong economic benefits. An estimated US$341·3 billion is lost globally each year from the unrealised benefits of breastfeeding to health and human development due to inadequate investment in protecting, promoting, and supporting breastfeeding.8

When possible, exclusively breastfeeding is recommended by WHO for the first 6 months of life, and continued breastfeeding for at least the first 2 years of life, with complementary foods being introduced at 6 months postpartum.9 Yet globally, many mothers who can and wish to breastfeed face barriers at all levels of the socioecological model proposed in The Lancet’s 2016 breastfeeding Series.4

Key structural barriers that undermine the breastfeeding environment10 include gender inequities; harmful sociocultural infant-feeding norms;11 income growth and urbanisation;12,13 corporate marketing practices13 and political activities that weaken breast-feeding protection policies; labour markets that poorly accommodate women’s reproductive rights and care work, reflecting major gender inequities; and poor health care that continues to undermine breastfeeding, including the medicalisation of birthing and infant care.14

These barriers exert a powerful influence on the main settings that influence breastfeeding: health systems, workplaces, communities, and households. Maternity care systems that do not follow the ten baby-friendly hospital Initiative (BFHI) steps15 continue to undermine breastfeeding because BFHI practices have a crucial role in preparing for and supporting lactation.15,16 Inadequate health-system support lowers the likelihood of breastfeeding due to poor staff training and marketing practices that are in violation of WHO’s International Code for the Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes17 (hereafter referred to as the Code), such as the distribution of commercial milk formula (CMF) samples and unjustified recommendations to introduce CMFs.13,18,19,20 Absent, inadequate, or poorly enforced maternity protection policies also undermine breastfeeding among working women through poor access to paid maternity and paternity leave, flexible scheduling to accommodate breastfeeding or appropriate breaks and facilities for breastfeeding or milk expression.21,22 For instance, literature from 2021 has emphasised that women working in the informal sector in the Philippines are not protected by maternity policies23 although this might change as a result of the resolution published by the Commission on Human Rights in early 2022.24 Communities and families often do not have the economic or educational resources and capabilities to adequately support breastfeeding.19,25,26

Key messages

• Commercial milk formula (CMF) products and artificial formula feeding cannot emulate the living and dynamic nature of breastmilk and the human interaction between mother and baby during breastfeeding. The unique and unparalleled qualities of breastfeeding bestow short-term and long-term health and development benefits.

• Only half of the newborn babies are put to the breast within the first hour of life, and about a third of babies in low-income and middle-income countries receive pre-lacteal feeds (mostly water and animal milk) before being put to the breast. Prelacteal feeding is strongly associated with delayed initiation of breastfeeding.

• Common infant adaptations to the post-birth environment, including crying, unsettled behaviour, and short night-time sleep durations, are often misconceived as signs of feeding problems. CMF marketing reinforces and exacerbates these misconceptions and makes unsubstantiated claims that CMFs can ameliorate these behaviours.

• Nearly half of mothers globally self-report insufficient milk (SRIM) as the primary reason for introducing CMFs in the first few months of life and for prematurely stopping breastfeeding. SRIM can generally be prevented or addressed successfully with appropriate support.

• Additional educational efforts are needed for health workers, families, and the public to inform them about normal early infant development, including common crying patterns, posseting, and short night-time sleep durations, to reduce the unnecessary introduction of CMFs and to prevent SRIM and early cessation of breastfeeding.

• Breastfeeding is not the sole responsibility of the mother. Reviews and country case studies indicate that improved breastfeeding practices at the population level are achieved through a collective societal approach that includes multilevel and multicomponent interventions across the socioecological model and different settings.

At the individual level, attributes and interactions specific to mothers and infants, such as mental health challenges, anxiety about unsettled infant behaviours, self-reported insufficient milk (SRIM), and low self-efficacy are challenges to breastfeeding that has not been adequately addressed within health systems to date.14, 27, 28

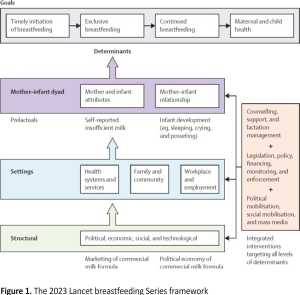

This Series provides a new vision of how to address breastfeeding protection, promotion, and support at scale through multilevel, equitable approaches. This vision addresses breastfeeding barriers and facilitators across all levels, from the structural to the individual, building on the conceptual model of the 2016 Lancet Breastfeeding Series (figure 1). In this Series paper, we examine how individual-level parent and baby attributes interact with breastfeeding determinants at other levels of the socioecological model, how these interactions drive outcomes, and what policies and interventions are necessary to achieve optimal breastfeeding. Structural and settings-based barriers to breastfeeding, including commercial determinants, are expanded on in the second and third papers of this Series,29, 30 which analyse the marketing of commercial milk formula and the political economy of infant and young child feeding (figure 1).

The papers in this Series were developed with a combination of research methods: (1) analysis of nationally representative survey data of children younger than 2 years, (2) commissioned systematic reviews (appendix pp 1–7), and (3) commissioned case studies.

We use the terms women and breastfeeding throughout this Series for brevity and because most people who breastfeed identify as women; we recognise that not all people who breastfeed or chest-feed identify as women.

Scientific advances in breastfeeding, breastmilk, and lactation

Breastfeeding is part of our species-specific biopsychosocial system that has evolved through our mammalian history to optimise the health and survival of both mothers and infants.3,11 Research published since the 2016 Lancet Breastfeeding Series1 has strengthened the evidence for the importance of interactions between mother and baby during breastfeeding. For example, suckling the breast releases oxytocin, prolactin, and other metabolites that foster mother–child bonding and reduce physiological stress for both.31 Hormones in breast milk stimulate appropriate infant appetite and sleep development, and hormonal, physiological, and metabolic changes during breastfeeding support the mother’s lifelong health in various ways. During breastfeeding, the immune systems of mothers and infants communicate with each other beyond passive immunity,32 and mothers transmit elements of their microbiota to their children through breastmilk. These good bacteria live in the gut and help fight disease, digest food, and regulate the child’s evolving immune system. They are influenced by several factors, including maternal diet and genetics, delivery method, antibiotic use, geographical location, and environment. 2,3,33 If breastfeeding is undermined, these evolutionary benefits are lost, as are the unique adaptations of breastmilk and breastfeeding to the individual mother, infant, and their circumstances.

Breastfeeding is much more than the transfer of breast milk from mother to baby. Suckling from the mother’s breast is a crucial part of the nurturing of infants. Direct breastfeeding versus feeding breastmilk with a bottle, cup, or spoon has important implications for infant health and development. In addition to influencing infant craniofacial structure and reducing the risk of malocclusion,34 there are newly recognised compositional differences in free amino acids and total protein in fore milk versus hind milk and the probable retrograde flow of infants’ oral microbiota into mother’s milk that takes place during breastfeeding.35, 36,37 The skin-to-skin contact occurring through direct breastfeeding supports maturing mechanisms, including temperature control, metabolism, and diurnal adaptation.16,38,39 Although the provision of expressed breastmilk in a bottle is superior to CMFs, direct breastfeeding compared with expressed breastmilk has been associated with lower rates of asthma, higher likelihood of the presence of the beneficial Bifidobacterium, and potentially better infant self-regulation of energy intake, thus protecting against obesity.36,40,41

Breastmilk itself is a highly adaptive live food source11,42,43 and, because of its dynamic nature, is more than its nutrient components. Breastmilk comprises nutritive and non-nutritive bioactive (eg, hormones, immune factors, oligosaccharides, and live microbes) that collectively and through complex interactions with each other—and with the biological, social, and psychological states of both mother and infant during breastfeeding— have a crucial role in healthy infant growth and development.2,3 Consequently, the composition of breastmilk changes during each feeding episode and as the infant develops over time, and in response to the physical and emotional state of the mother–child dyad. That the interactions and outcomes of breastfeeding cannot be artificially replicated is clear from past and new evidence.

Understanding breastmilk and the complex biopsychosocial system of breastfeeding

Since the publication of the 2016 Lancet Breastfeeding Series,1 discovery has further shown how the nutritional, microbial, and bioactive components of breastmilk engage with each other, and how the composition of breastmilk varies with mother–baby interactions during breastfeeding. CMF and formula feeding cannot replicate the complexity and benefits of human milk and breastfeeding.

The specific bacteria found in breast milk vary between and within populations, with several maternal and delivery-related factors influencing the variations in the predominant species.44 Some evidence shows the infant’s oral microbiota might also contribute to the breastmilk microbiome, passing through the nipple into the mother’s breast while breastfeeding.35,36 Furthermore, the breastmilk microbiome contributes to the relatively low abundance of antibiotic-resistance genes, particularly among infants breastfed for at least 6 months.45 Additional studies show that breastmilk extracellular vesicles contain at least 633 proteins that were previously not known to exist. These novel proteins appear to be involved in regulating cell growth and inflammation, and in signaling pathways that promote oral epithelial integrity.46,47 These extracellular vesicles also contain microRNA, which regulates gene expression that controls growth, inflammation, and the activation of T-regulatory cells, which in turn can protect against autoimmunity and necrotising enterocolitis.48,49

The breastmilk microbiome and its vast array of human milk oligosaccharides have gained recognition for their interdependence and their effect on infant health; however, new findings regarding the free amino acid content of breastmilk show the multifunctionality of this previously overlooked component of the biological system. Glutamate and glutamine are the most abundant free amino acids in breast milk and together account for more than 70% of the free amino acids in breast milk at any point during lactation.37 Research findings from multiple geographical locations indicate that the concentrations of several free amino acids (glutamine, glutamate, glycine, serine, and alanine) increase over the first 3 months of lactation, and free glutamine concentrations probably vary by infant sex.37,50,51

Free glutamate promotes the growth of intestinal epithelial cells, whereas both free glutamate and free glutamine have immunomodulatory actions and might modify the gut microbiota.37,51 Furthermore, free glutamate concentrations are directly related to the rate of infant weight gain.52,53,54,55 Given the dynamic variation in proportions of these free amino acids even within one mother–baby dyad, the addition of multiple free amino acids to CMFs cannot replicate the free amino acid profile of breastmilk, nor its effect on infants.

Likewise, only breastfeeding provides newborn babies, infants, and young children with protective antibodies acquired by maternal vaccines and the mother’s own exposure to antigens and allergens. For instance, during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, numerous studies reported the presence of neutralising antibodies in breast milk following vaccination or maternal infection.56,57,58 Breastfeeding offers infants and young children their earliest form of immune protection against infectious disease.59

Although pioneering progress has been made over the past decade in exploring the biopsychosocial system of breastfeeding, we are only beginning to understand the complex biology of this unique functional food and the social and psychological implications of breastfeeding interaction. 2,3 To better understand the components of breastmilk, we need to clarify the roles and interactive relationships between several other components, including hormones (leptin and ghrelin), white blood cells, antimicrobial peptides, cytokines, and chemokines. The complex, interactive, and personalised nature of the biological system of breastmilk, and the unique and beneficial features of the breastfeeding relationship, are beyond replication.

Prelacteal feeds and early breastfeeding in low-income and middle-income countries

Global trends in exclusive breastfeeding among children younger than 6 months and up to 2 years of age in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) were published in 2021.60 High-income countries were not included because there is almost no nationally representative data on prelacteal feeds and early breastfeeding outcomes in these settings. However, less attention has been given to timely breastfeeding initiation (within an hour of birth) and prelacteal feeds (ie, foods other than breastmilk offered during the first 3 days after delivery61,62) given to infants before the onset of lactation in LMICs. These practices influence breastfeeding success and neonatal mortality rates through complex and diverse pathways. 63,64,65

Prelacteal feeds encompass a range of substances given to newborn babies consisting of water, milk, and milk-based substances, including CMF products. In LMICs, rice or maize water, sugar water, herbal mixtures, honey, ghee, and morsels of adult staple foods are also sometimes given.66 Some of these substances are intended to provide nourishment to a newborn baby, especially if colostrum is discarded. 67 Others, such as honey and dates, are given as part of cultural practices and as laxatives to clear meconium.68 Even when immediate and exclusive breastfeeding is achieved, pre-lacteal feeds affect the neonate’s establishment of normal microbiota in the gastrointestinal tract.69,70 Several studies report that the administration of pre-lacteal feeds delays breastfeeding, adversely affects lactation, and is associated with SRIM and premature supplementation or cessation of breastfeeding;71,72 a relationship investigated in this Series paper.

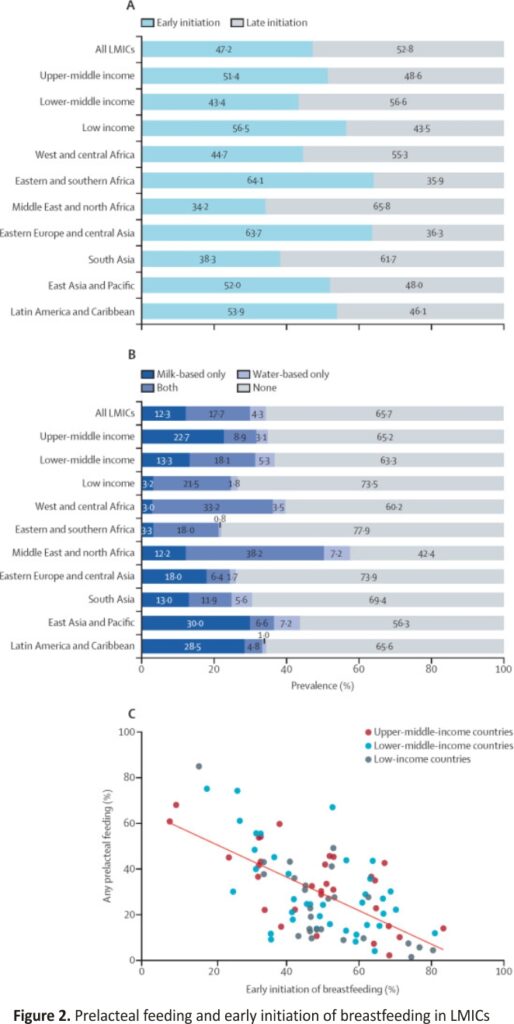

We used data from demographic and health surveys and multiple indicator cluster surveys (obtained from the International Center for Equity in Health database) to describe the prevalence and trends in early breastfeeding initiation and pre-lacteal feeding between 2000 and 2019 (figure 2). A total of 103 LMICs had nationally representative data on the timely initiation of breastfeeding since 2010 (appendix pp 8–11). Fewer than half (47·2%) of all children in these countries were breastfed within the first hour of life. The lowest prevalence was reported in the Middle East and North Africa, and in the South Asia regions.

Weighted by the number of children younger than 2 years in each country. (A) Early initiation of breastfeeding among children younger than 2 years by region. Early initiation of breastfeeding is defined as the proportion of children who were put to the breast within the first hour after birth. (B) Use of pre-lacteal feeds in 94 LMICs by income group and world region (appendix pp 38–41). Estimates were weighted by the population size of children in each country, obtained from the World Bank population estimates. (C) Correlation between pre-lacteal feeding and early initiation of breastfeeding, by country income groups. Pearson’s r=–0·63 (p<0·0001). LMICs=low-income and middle-income countries.

For 83 countries, time trends could also be described (appendix pp 12–24). The pooled prevalence of timely initiation increased from 29·7% (95% CI 21·7–37·7) in 2000 to 50·7% (95% CI 43·5–57·8) in 2019, or 1·1 percentage points per year, on average (appendix pp 25–37). Over the same period, exclusive breastfeeding at ages 0–5 months increased by 0·7 percentage points per year (0·51–0·88; p<0·0001) to reach 48·6% (95% CI 41·9–55·2) in 2019. Improvements were seen in all regions of the world except for the Middle East and North Africa, although the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding is still far from the World Health Assembly goal of reaching at least 70% by 2030.60

For all LMICs combined since 2010, 34·3% of children received pre-lacteal feeds including 12·3% who received a milk-based pre-lacteal feed only, 17·7% a water-based pre-lacteal feed, and 4·3% who received both. Milk-based pre-lacteal feeds were more common in higher-middle-income countries, whereas water-based pre-lacteal feeds were more common in low-income countries. We found a highly significant inverse correlation between early initiation of breastfeeding and the use of pre-lacteal feeds in an ecological analysis of these data.

Unfortunately, national data on pre-lacteal feeding is not available for high-income countries, although numerous hospital studies report that CMF is given to breastfed newborn babies before discharge.73,74 For example, a study in the USA found that 62% of maternity facilities nationwide supplemented more than 20% of breastfed babies with formula during their hospital stay.75 Likewise, almost a third of newborn babies in Australia receive in-hospital supplementation.76

In summary, about one in three neonates in LMICs receive pre-lacteal feed substances during the first 3 days after birth, and only one in two neonates are breastfed within the first hour of life. The use of pre-lacteal feeds is strongly associated with delayed initiation of breastfeeding and can lead to the premature cessation of breastfeeding.62

Infant behaviour, SRIM, and the early introduction of CMF

Humans are born in an immature state requiring intensive caregiving and remain immature for an extended period compared with other primate species.77 Metabolic and obstetric constraints, placental effects, and the adaptive importance of an extended period of social interaction and learning are the main explanations for these unique aspects of human development.77 Neonates rely on closeness to caregivers for survival and physiological regulation.77 Skin-to-skin contact and breastfeeding support maturing mechanisms, including temperature control, metabolism, and diurnal adaptation.16,38,39 Because of their physiological immaturity, neonates are ill-equipped to deal with many sensory and other aspects of the postnatal environment (eg, feeding and sleeping) and express their discomfort in highly adaptive infant crying, which signals the need for help and support from caring adults.

Unsettled infant behaviours are the most frequent reasons for health consultations in the first months of life and are usually interpreted by mothers, their social networks, and frequently their health providers as signs of infant digestive problems, allergies, adverse reactions to breastmilk or a particular brand of CMF, or persistent hunger resulting from insufficient milk.78,79,80 Our systematic review of 22 studies across countries with different income levels concluded that unsettled infant behaviours, especially persistent crying, can lead parents to believe that CMF supplementation or specialised CMF formulas are needed.81

Crying, fussiness, posseting, and short night-time sleep duration are common in early infancy. They are distressing for parents and are consistently reported to undermine parental self-efficacy.82 For example, up to 50% of healthy infants from birth to 3 months of age have at least one episode of regurgitation per day.83 A review of 28 diary studies84 found the mean time spent fussing or crying per day in the first 6 weeks of life was around 2 h a day, varying from 1 h to 3 h. Mean duration dropped rapidly after 6 weeks of age to about 1 h by 10–12 weeks of age. Interrupted night-time sleep, posseting, and crying often co-occur,85,86 partly because crying frequently accompanies both infant waking and regurgitation. Even conservative estimates indicate that fewer than 5% of infants identified by parents as crying excessively are found to have any underlying disease or illness requiring further investigation or treatment.80,87 Findings are similar for sleep patterns and posseting. Reports of objective measures of these infant developmental adaptations and parental anxiety are seldom found.88, 89

There are many reasons why infants cry, including hunger, changing temperatures, or other discomfort. Several parental responses successfully reduce crying: attending to immediate causes, such as a wet diaper; soothing and comforting techniques, such as carrying, rocking, and massaging;90,91 and feeding, especially breastfeeding, which involves close body contact,92 and suckling reduces distress and is incompatible with crying.93 However, in the absence of skilled and knowledgable support and reassurance, many parents change their feeding from breastfeeding to CMFs; from one CMF to another; or to specialised CMFs that, in violation of the Code,17 claims without evidence to reduce allergies, help with colic, and prolong night-time sleep (in the second paper in this Series29).94,95

Although understudied, behavioural cues of fussiness are commonly interpreted by parents, family members, and healthcare staff as an indication that breastmilk quality or quantity is inadequate to satisfy their infant.75,96 CMF marketing messages exploit mothers’ insecurities about their milk and their ability to satisfy and calm their baby97,98,99 by framing typical baby behaviours as pathological and offering CMFs as solutions (in the second paper in this Series29). Hence, it is not surprising that SRIM is the reason given by more than half of mothers globally for introducing CMFs before 6 months postpartum, and by a third of mothers for stopping breastfeeding.62

SRIM has been conceptualised as “a state in which a mother has or perceives that she has an inadequate supply of breastmilk to either satisfy her infant’s hunger and [or] to support her infant’s adequate weight gain.”100 Globally, 44·8% of mothers report introducing CMF because of SRIM.72 The extent to which SRIM is related to perceived or actual inadequate milk supply, milk nutritional quality, or both, has not been fully elucidated.72,80,101 Research indicates that a mother’s self-assessment of milk supply is frequently based on perceptions of infant satiety and satisfaction, signaled by infant behaviours, especially crying and fussiness.80,101,102 Inadequate lactation counseling and stress-management skills by health workers in the days after birth, together with misunderstanding among caregivers, family members, or health providers of the multifactorial causes of infant behaviours (eg, crying) and the marketing of CMFs as solutions to unsettled infants, can influence parents to introduce CMFs. Introducing CMFs can reduce suckling and can result in actual insufficient milk production. 65,103,104

Three systematic reviews found that the reasons for SRIM vary according to infant age, maternal characteristics, maternal mental health status,19, and stage of lactation105 (ie, colostrum, onset of lactation, establishment, and maintenance of lactation). In a systematic review of 120 studies,72 key risk factors for SRIM were multilevel and multi- factorial: (1) maternal socioeconomic and psychosocial characteristics (eg, household income, maternal age, marital status, parity, education and employment status, self-efficacy or confidence in their ability to breastfeed, BMI, and weight gain during pregnancy); (2) delivery practices (eg, caesarean section delivery, prolonged stage II labour, use of pain medication or anaesthesia, and maternity hospitals that do not have good breastfeeding practices, such as putting the infant to the breast within the first hour postpartum or skin-to-skin care), (3) breastfeeding challenges (eg, absence of previous breastfeeding experience, weak breastfeeding intention during pregnancy, having no access to breastfeeding support [especially in the days after birth], low frequency of nursing, maternal beliefs, and negative experiences with breastfeeding), and (4) baby behaviours (eg, fussiness and infant feeding difficulties, which can cause nipple pain and breast engorgement due to poor latching).62, 81

Since both pre-lacteal feeds and early introduction of CMFs are negatively associated with exclusive breastfeeding and breastfeeding duration,61,62,71 mothers and healthcare workers require better education on how to best address concerns about infants’ developmental behaviours while maintaining successful breastfeeding. Infant developmental patterns and parental concerns about them need to be addressed through improved scientific study and public health practice to enhance breastfeeding guidance, starting in pregnancy and reinforcing postpartum.65,106,107 Understanding how perceptions of infant behaviour influence caregivers’ infant feeding decisions92 and how such understanding can be used to improve breastfeeding support is important.

Globally, SRIM continues to be one of the most common reasons for introducing CMF and stopping breastfeeding.72 Parents and health professionals frequently misinterpret typical, unsettled baby behaviours as signs of milk insufficiency or inadequacy. In our market-driven world, and in violation of the Code17 the CMF industry exploits parents with concerns about these behaviours with product claims and advertising messages. This marketing leads to early CMF introduction, which in turn reduces infant suckling and could also result in complete breastfeeding cessation.13, 81,99 There are widespread, unmet needs for exclusive and continued breastfeeding support in the face of these marketing dynamics and feeding challenges (in the second paper in this Series).29 With appropriate counseling support, in most cases effective breastfeeding and milk production can be increased and maintained.

Effective breastfeeding interventions to address healthcare, social, and behavioural barriers

Building on evidence that breastfeeding rates can be rapidly improved by scaling up known interventions, policies, and programmes,4 we assessed the reviews published between 2016 and 2021 to provide more depth and strengthen the evidence base for effective breastfeeding interventions,108 many of which are needed to address the breastfeeding challenges described previously. We assessed the quality of reviews and their distribution across settings and elements of the socio-ecological model.

Consistent with The Lancet’s 2016 Series’ findings, research continues to focus on settings of high and upper-middle income (47 of 115 reviews, 41%), or a combination of settings with different income levels (48 of 115, 42%) that still tilts towards high-income countries even though the majority of births annually are in LMICs. Additionally, research remains primarily centered on health systems (72 of 115 reviews, 63%), followed by community and home settings (45 of 115, 39%), and the workplace (10 of 115, 9%). Few reviews (7 of 115, 8%) addressed structural interventions, a substantial gap discussed in the second and third papers in this Series.29,30

In the workplace, evidence reinforces the importance of fully paid maternity leave in facilitating breastfeeding prevalence and duration, although disparities in access and utilisation persist109,110, and birth parents in the informal sector have little, if any, protection.26 Furthermore, to achieve equitable working conditions for breastfeeding mothers, organisational and social changes need to occur.15 Workplaces could facilitate breastfeeding, especially when part of a broader set of parental support policies and practices. Written policies that describe the role of each actor (ie, managers and co-workers) in supporting breastfeeding in the workplace are particularly important.111,112 Given that many people in LMICs work in the informal economy or are not entitled to maternity benefits when they become unemployed, even if formerly employed in the formal sector (a situation that increased during the COVID-19 pandemic113), providing them with maternity benefits through cash transfers and other benefits is key. Research shows that this approach is feasible for middle-income countries such as Brazil, Ghana, Indonesia, Mexico, and the Philippines.114,115

Within health systems, reviews have strengthened the evidence base for implementing early skin-to-skin care,16,116 kangaroo mother care (ie, skin-to-skin with the mother or caregiver),117,118 rooming in (ie, keeping the infant in the same room as the mother),119 and cup feeding120,121 at scale because these interventions consistently improved breastfeeding outcomes for both preterm and full-term infants. Implementation of the BFHI is also associated with better breastfeeding outcomes within the hospital and the community, which is not surprising given that it includes the interventions previously mentioned, allowing them to synergise with each other.15,122,123,124,125

These evaluations, together with country case studies, show the importance of multilevel and multicomponent approaches to create the enabling environment needed to effectively protect, promote, and support breastfeeding moving forward (discussed in the third paper in this Series30).28,126 Much of the innovation in interventions in the past two decades has emerged via multi-component programmes addressing the different domains of the socioecological model (figure 1). Robust evaluations show a greater effect on breastfeeding outcomes at scale than interventions that are not well coordinated across sectors and different levels of the socioecological model.127,128,129,130 For instance, BFHI can provide an important springboard for multilevel and multi-component interventions that involve the engagement of community and individual families.129,130,131,132 Community-based interventions could engage health-care providers, community health workers, and family members,125,133 particularly fathers134,135,136 and grand-mothers,137,138 with education and home visits that span the prenatal and postnatal periods.124,139,140 Evidence indicates that home visits can be effectively provided by both trained health workers and community health workers.141,142 Community health workers amplify networks of education and support across health care, community, and family settings,133 and might be particularly helpful in supporting historically marginalised communities143 and in complex situations like humanitarian emergencies.127 Additionally, multicomponent interventions were particularly effective in achieving the greatest effect on breastfeeding outcomes, suggesting that discrete interventions complement each other.128,129,130

The complexity and challenges involved in designing, delivering, and evaluating multicomponent breastfeeding support programmes that operate across the different levels of the socioecological model are important to acknowledge.4 Although much more implementation science research is needed, the evidence makes clear the importance of breastfeeding interventions to be multisectoral and rooted in sound health and social policies. For instance, efforts to improve early initiation of breastfeeding in Viet Nam have been designed in the context of high rates of births by cesarean section, an obstetric practice that is common in China and Latin America and becoming more common in sub-Saharan Africa.144 Despite achieving positive effects, efforts to improve exclusive breastfeeding in Viet Nam are also adversely affected by the mother’s employment, especially when self-employed, which leads to feeding practices that combine breastfeeding with CMFs. This example further emphasises the importance of incorporating social policy change into efforts aiming to improve breastfeeding outcomes.145

Improvements to exclusive breastfeeding over the past decade

Several countries have translated knowledge into action to improve exclusive breastfeeding outcomes.146 This section synthesises the findings and conclusions from case studies in Burkina Faso, the Philippines, the USA, and Mexico, commissioned for this paper by WHO. The methods and findings have been published elsewhere. 146 These countries were selected for geographical diversity (sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, North America, and Latin America), and for meeting the a priori selection criteria:146 exclusive breastfeeding rates increased in the past 10 years, and breastfeeding policies and programmes were documented during the timeframe when breastfeeding outcomes improved (appendix pp 42–46), and a wide range of key informants were available for interview. Following the breastfeeding gear model126 and the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance (RE-AIM) implementation framework147 as a guide to analyses, we show the path that each country followed to improve exclusive breastfeeding practice.

Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso invested in training and programme delivery with a multilevel strategic plan (2012–25) to improve optimal infant and young child feeding practices, including at the community level, through the training of traditional leaders and the creation of mother-to-mother support groups. It has also promoted and mounted advocacy through the government, UNICEF, and Alive & Thrive, including initiatives such as the Stronger with Breastmilk Only campaign to raise awareness of the importance of exclusive breastfeeding. This campaign promotes breastfeeding only, responding to the cues of the infant, and stopping the practice of giving water, other liquids, and foods in the first 6 months of life throughout West and Central Africa.

The Philippines

Breastfeeding protection, promotion, and support are included in many national multicomponent policies and development strategies in the Philippines, reflecting political commitment. Additionally, there is the commitment to including breastfeeding promotion, protection, and support as a part of national, cost-effective, time-bound, multicomponent packages such as early essential newborn care, an example of one of the specific investments that link the health provider with support for interpreting baby behaviour that affects early breastfeeding initiation. In addition, the Philippines has strengthened national legislation by approving and enacting the 105-day extended maternity leave law, which extends paid maternity leave from 60 days to 105 days, and the implementation of an official database of reported violations of the Code.17 These efforts have been strongly influenced by breastfeeding coalitions that have actively resisted the CMF industry’s political activities (in the third paper of this Series).30

The USA

Despite lacking a federally mandated paid leave, the USA has strong programme delivery coupled with regularly collected breastfeeding data reported annually by states. Local data serve as a basis for feedback to hospitals so they can implement evidence-based strategies to improve breastfeeding support. The USA continues to accredit an increasing number of baby-friendly hospitals each year. The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children, which covers half of the births in the USA annually, is increasingly investing in breastfeeding counseling as it continues to change its benefits structure to support more mothers to choose breastfeeding rather than mixed feeding or CMFs.148 In addition, the 2010 Affordable Care Act expanded the number of people with health insurance and the US Department of Health and Human Services required health insurers to cover lactation support services, which has also improved coverage of breastfeeding support.

Mexico

Mexico implemented a national breastfeeding strategy (2014–18) to coordinate supportive actions. The becoming breastfeeding-friendly policy toolbox 149,150 has been applied three times since 2016 to strengthen policies and programmes to improve breastfeeding outcomes. Using this policy, the Mexican National Academy of Medicine issued its first position statement151 on the need to improve breastfeeding practices in Mexico. Scores were generated from the policy across eight domains: advocacy, political will, legislation, financial resources, workforce development, and programme implementation, behaviour change communication campaigns, monitoring and evaluation, and coordination. Specific policy recommendations were made from the findings, including improved maternity benefits, workforce development, coverage and quality of BFHI, and decentralised coordination. Any breastfeeding, exclusive breastfeeding, and breastfeeding duration have improved since the launch of the first policy assessment.152 Breastfeeding practices are monitored through nationally representative surveys, including the Health and Nutrition National Survey, the National Survey of Demographic Dynamics, and UNICEF’s Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys.

These examples show the importance of understanding breastfeeding behaviours and barriers in their local context and responding with multicomponent policies and programmes that involve both commitment and coordination among different sectors (government, international organisations, civil society, academia, and parents). The importance of robust data for monitoring, accountability, and programme adjustments is also emphasised. Political commitment in all four countries was key for improving exclusive breastfeeding, although in Mexico and Burkina Faso the budget allocation was clearly insufficient. In Mexico, the change of government affected the prioritisation of public health issues, including breastfeeding. Laws to protect breastfeeding were insufficient in all countries, but the Philippines had the strongest breastfeeding protection legislation related to Code17 and maternity benefits. The advocacy of international and civil society organisations, and concrete actions to enforce the Code, were evident in Burkina Faso, the Philippines, and Mexico. Nevertheless, aggressive marketing by the CMF industry remains an enormous challenge for all four countries.

Discussion

In most cases, breastfeeding has a major positive effect on the health and well-being of infants and children, mothers, and society. Globally, most mothers can and are choosing to breastfeed, but many who can breastfeed cannot breastfeed for as long as recommended, even when they want to.153,154,155 Mothers and their families require support to be able to maintain breastfeeding while having the freedom and support to continue to participate in other areas of life as they choose, such as education and employment.156,157 We know what needs to be done to improve breastfeeding outcomes: follow an approach that should be grounded in public health principles with an equity framework 10,158,159,160,161,162,163 and a human rights approach at its core.164 To ensure all infants and young children receive the best possible nutrition and care there must be a society-wide enabling environment for breastfeeding, which is protected and sustained by political commitment, policies, and resources. 4,126

Discoveries in breastfeeding and breastmilk research highlight the large difference in quality between breastmilk and CMFs, leaving no doubt that breastfeeding promotes healthy and sustainable food systems.13 Since the 2000s, early breastfeeding initiation almost doubled globally, reaching 50% in 2019. Furthermore, over the past decade, exclusive breastfeeding among infants younger than 6 months increased by 0·7 percentage points per year, reaching 49% in 2019.60 Despite these important improvements, there are very few countries on track to meet the World Health Assembly target of 70% of infants being exclusively breastfed by 2030, and there are still large disparities across and within countries.12,13,165,166 There are declining breastfeeding trends in low-income countries,60 mainly because infant and young child feeding practices are constrained and shaped by powerful structural influences, including social and commercial determinants, at all levels of the socioecological model (in the second and third papers of this Series29,30).11 Clearly, an approach by the whole of society is needed for mothers to be able to meet their breastfeeding goals.

It is of great concern that more than a third of all neonates received pre-lacteal feeds during the first 3 days after birth because this practice is negatively associated with timely breastfeeding initiation and breastfeeding duration.61,71 An analysis by UNICEF and WHO167 found that timely initiation rates are nearly twice as high among newborn babies who receive only breastmilk compared with newborn babies who receive milk-based supplemental feeds in the first 3 days of life. Health-system and community-based interventions are needed globally to prevent the introduction of pre-lacteal feeds and counteract the harmful influence of CMF marketing on health systems and communities.

At the dyadic and family levels, unsettled baby behaviours, including crying, posseting, and short nocturnal sleep duration, influence infant feeding decisions.39 Although overwhelmingly an expression of normal infant developmental processes rather than clinical conditions, these behaviours can prompt cessation of exclusive breastfeeding because they are interpreted by many parents as inadequate breastmilk supply or infant pathology requiring special feeding products. The CMF industry exploits and pathologises normal patterns of infant development in ways that exacerbate parental insecurities about feeding.97,98,99,168,169,170

The misconception of typical human infant behaviour as pathological, and its exploitation by the CMF industry, are important factors of SRIM, which is a key reason for the introduction of CMF and the premature termination of breastfeeding. Preventing SRIM requires effective lactation management and social support during pregnancy, along with maternity facilities that follow policies and practices conducive to initiating breastfeeding without commercial influence. Supporting breastfeeding self-efficacy and combating CMF marketing influence through evidence-based information and support is paramount to preventing SRIM, the introduction of pre-lacteal feeds, or the early introduction of CMF, which interferes with lactation.61

For these reasons, universal access to improved breastfeeding-supportive maternity care, evidence-based breastfeeding counseling, and public and health worker education are crucial for preventing common early lactation problems, avoiding attempts to address common behaviours of infant developmental by introducing CMFs and helping mothers improve their breastmilk production and self-efficacy. 62,65,101,171,172

The BFHI, community-based peer counseling, and maternity benefits for mothers working in both the formal and informal sectors are evidence-based approaches to improving breastfeeding outcomes. Protecting families from CMF marketing practices must take a comprehensive approach that addresses misleading advertisements and the CMF industry’s influence on healthcare professionals and their societies, researchers, and the entire healthcare environment (in the second paper of this Series).29 In agreement with previous reviews,4,126 well-coordinated, multi-component, and multilevel programmes are the most promising approaches for scaling up and sustaining effective breastfeeding programmes, but more political commitment and financial investments are needed from governments.4,146 Increased advocacy by international, civil society, and health-professional organisations must be translated into concrete legislative actions to implement, monitor, and enforce the Code,17 and to remove the influence of CMF industry on SRIM and misinterpretation of infant development, mothers, health systems, and society.

Maternity protection policies have improved in the past decade due to national laws informed by the International Labour Organization standards,173 or via initiatives to improve the breastfeeding environment at the workplace, but more progress is needed. Absent, inadequate, or poorly enforced maternity protection policies undermine breastfeeding among working mothers through restricted access to paid maternity. For instance, in 2021, 649 million women of reproductive age lived in countries that do not meet the International Labour Organization standards for maternity leave (eg, a minimum period of 14 weeks paying the mother at least two-thirds of her previous earnings, covered by compulsory social insurance or public funds) and flexible scheduling to accommodate milk expression or breastfeeding.173

In conclusion, much more is known now than previously about the biopsychosocial system of breastfeeding, and that it cannot be matched by CMF. A wealth of evidence shows how to create more enabling environments and deliver programmes to support breastfeeding at scale (panel). When direct breastfeeding is not possible, WHO guidance on infant and young child feeding should be followed to support responsive human-milk feeding and any other replacement feeding as necessary. Long-term studies of national or subnational trends in breastfeeding are essential as we look ahead to the next decade. Special attention needs to be paid to the rapidly evolving and adapting marketing of CMFs, including through toddler and maternal milk, and through products targeted at the substantial proportion of small babies (eg, preterm and babies of low birthweight) born in LMICs (20% of babies born in sub-Saharan Africa and 30% in south Asia).174 These industry interventions deliberately violate Code 17 and prevent progress in improving breastfeeding outcomes globally.98,169 The second paper in this Series 29 addresses how CMF marketing operates. The political and economic forces that enable this commercial influence and undermine breastfeeding in the context of major gender inequities are presented in the third paper of this Series.30

Panel

Recommendations

The following policy and programmatic actions are needed to support mothers who want to breastfeed:

• Investment in public awareness and education is needed so that policymakers and the global general public recognise the growing scientific evidence that breastfeeding is the evolved, appropriate feeding system for optimising both mother and infant survival, health, and wellbeing. Misconceptions about the equivalence of commercial milk formula (CMF) to breastmilk must be corrected through extensive health education programmes directed towards the public and policymakers.

• Skilled counseling and support should be provided prenatally and postpartum to all mothers to prevent and address self-reported insufficient milk and avert the introduction of pre-lacteal feeds or CMF early on because they are major risk factors for the premature termination of exclusive breastfeeding and any breastfeeding.

• Health professionals, mothers, families, and communities must be provided with better educational support and skill development, free from commercial influence, to under- stand unsettled baby behaviours as an expected phase of human development. Healthcare providers should offer anticipatory guidance, starting in pregnancy and continuing postnatally, to prepare mothers and other caregivers for how to respond to unsettled baby behaviours and industry marketing that misconstrues these behaviours and violates the WHO Code.17 This help will facilitate continued, successful breastfeeding.

• Intersectoral policies (eg, health, social development, education, labour, and regulatory sectors) that address multilevel barriers to breastfeeding must be implemented to enable mothers to breastfeed their children optimally for as long as they, or their babies, desire. These policies must be grounded in equity, human rights, and public health principles, and enabled through system-wide political and societal commitment to breastfeeding.

The 2023 Lancet Breastfeeding Series Group

Phillip Baker (Australia), Aluisio J D Barros (Brazil), France Bégin (Equatorial Guinea), Donna J Chapman (USA), Amandine Garde (UK), Lawrence M Grummer-Strawn (Switzerland), Gerard Hastings (UK), Sonia Hernández-Cordero (Mexico), Gillian Kingston (UK), Chee Yoke Ling (Malaysia), Kopano Matlwa Mabaso (South Africa), David McCoy (Malaysia), Purnima Menon (India), Paulo Augusto Ribeiro Neves (Brazil), Rafael Pérez-Escamilla (USA), Ellen Piwoz (USA), Linda Richter (South Africa), Nigel Rollins (Switzerland), Katheryn Russ (USA), Gita Sen (India), Julie Smith (Australia), Cecília Tomori (USA), Cesar G Victora (Brazil), Benjamin Wood (Australia), Paul Zambrano (Philippines).

a. Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Yale School of Public Health, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA

b. Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, Baltimore, MD, USA

c. Research Center for Equitable Development (EQUIDE), Universidad Iberoamericana, Mexico City, Mexico

d. Institute for Physical Activity and Nutrition, Deakin University, Geelong, VIC, Australia

e. International Center for Equity in Health, Federal University of Pelotas, Pelotas, Brazil

f. UNICEF, Malabo, Equatorial Guinea

g. Windsor, CT, USA

h. Department of Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health, WHO, Geneva, Switzerland

I. Department of Nutrition and Food Safety, WHO, Geneva, Switzerland

j. International Institute for Global Health, United Nations University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

k. International Food Policy Research Institute, New Delhi, India

l. Washington, DC, USA

m. Centre of Excellence in Human Development, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

Contributors

RP-E developed the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the design, writing, and revision of the final draft of the manuscript. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Declaration of interests

NR received grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation during the conduct of this study. All other authors declare no competing interests.

References

1. CG Victora, R Bahl, AJ Barros, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect Lancet, 387 (2016), pp. 475-490

2. L Bode, AS Raman, SH Murch, NC Rollins, JI Gordon Understanding the mother–breastmilk–infant “triad” Science, 367 (2020), pp. 1070-1072

3. P Christian, ER Smith, SE Lee, AJ Vargas, AA Bremer, DJ Raiten The need to study human milk as a biological system Am J Clin Nutr, 113 (2021), pp. 1063-1072

4. NC Rollins, N Bhandari, N Hajeebhoy, et al. Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? Lancet, 387 (2016), pp. 491-504

5. BL Horta, N Rollins, M Dias, V Garcez, R Pérez-Escamilla Systematic review and meta-analysis of breastfeeding and later overweight or obesity expands on previous study for World Health Organization Acta Paediatr (2022) published online June 21. https://doi.org/10.1111 /apa.164 60

6. AF Louis-Jacques, AM Stuebe Enabling breastfeeding to support lifelong health for mother and child Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am, 47 (2020), pp. 363-381

7. CG Victora, BL Horta, C Loret de Mola, et al. Association between breastfeeding and intelligence, educational attainment, and income at 30 years of age: a prospective birth cohort study from Brazil Lancet Glob Health, 3 (2015), pp. e199-e205

8. D Walters, LTH Phan, R Mathisen The cost of not breastfeeding: global results from a new tool Health Policy Plan, 34 (2019), pp. 407-417.

9. WHO Breastfeeding. https://www. who.int/health-topics/breast feeding#tab= tab_1 (2021),

10. C Tomori, E Quinn, AE Palmquist Making space for lactation in the anthropology of reproduction S Han, C Tomori (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Anthropology and Reproduction, Routledge, New York, NY (2022), pp. 527-540

11. C Tomori, AE Palmquist, EA Quinn Introduction C Tomori, AE Palmquist, EA Quinn (Eds.), Breastfeeding: new anthropological approaches, Routledge, New York, NY (2018), pp. 1-28

12. PAR Neves, G Gatica-Domínguez, NC Rollins, et al. Infant formula consumption is positively correlated with wealth, within and between countries: a multi-country study J Nutr, 150 (2020), pp. 910-917

13. P Baker, T Santos, PA Neves, et al. First-food systems transformations and the ultra-processing of infant and young child diets: the determinants, dynamics, and consequences of the global rise in commercial milk formula consumption Matern Child Nutr, 17 (2021), Article e13097

14. DS Patil, P Pundir, VS Dhyani, et al. A mixed-methods systematic review on barriers to exclusive breastfeeding Nutr Health, 26 (2020), pp. 323-346

15. R Pérez-Escamilla, JL Martinez, S Segura-Pérez Impact of the baby-friendly hospital initiative on breastfeeding and child health outcomes: a systematic review Matern Child Nutr, 12 (2016), pp. 402-417

16. ER Moore, N Bergman, GC Anderson, N Medley Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 11 (2016), Article Cd003519

17. WHO Code and subsequent resolutions https://www.who. int/teams/nutrition-and-food-safety/food-and-nutrition-actions-in-health-systems/code-and-subsequent-resolutions,

18. WHO, UNICEF How the marketing of formula milk influences our decisions on infant feeding World Health Organization, Geneva (2022)

19. OO Balogun, A Dagvadorj, J Yourkavitch, et al. Health facility staff training for improving breastfeeding outcome: a systematic review for step 2 of the baby-friendly hospital initiative Breastfeed Med, 12 (2017), pp. 537-546

20. GE Becker, P Zambrano, C Ching, et al. Global evidence of persistent violations of the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes: a systematic scoping review Matern Child Nutr, 18 (suppl 3) (2022), Article e13335

21. M Vilar-Compte, S Hernández-Cordero, M Ancira-Moreno, et al. Breastfeeding at the workplace: a systematic review of interventions to improve workplace environments to facilitate breastfeeding among working women Int J Equity Health, 20 (2021), p. 110

22. K Litwan, V Tran, K Nyhan, R Pérez-Escamilla How do breastfeeding workplace interventions work?: A realist review Int J Equity Health, 20 (2021), p. 148

23. Alive & Thrive Research on maternity entitlements for women in the informal economy informs new senate bill in the Philippines https://www.aliveandthrive.org/ en/news/research-on-maternity-entitlements-for-women-in-the-informal-economy-informs-new-senate-bill-in-the (Aug 4, 2021),

24. Commission on Human Rights Resolution CHR (V) no.POL2022-004 https://chr.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/CHR-V-No.POL2022-004-A-Situation-Report-on-Women-in-the-Informal-Sector.pdf

25. H Reis-Reilly, N Fuller-Sankofa, C Tibbs Breastfeeding in the community: addressing disparities through policy, systems, and environmental changes interventions J Hum Lact, 34 (2018), pp. 262-271

26. G Bhan, A Surie, C Horwood, et al. Informal work and maternal and child health: a blind spot in public health and research Bull World Health Organ, 98 (2020), pp. 219-221

27. SS Cohen, DD Alexander, NF Krebs, et al. Factors associated with breastfeeding initiation and continuation: a meta-analysis J Pediatr, 203 (2018), pp. 190-196 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds. 2018.08.008

28. IK Sharma, A Byrne Early initiation of breastfeeding: a systematic literature review of factors and barriers in south Asia Int Breastfeed J, 11 (2016), p. 17

29. N Rollins, E Piwoz, P Baker, et al. Marketing of commercial milk formula: a system to capture parents, communities, science, and policy Lancet (2023)

30. P Baker, JP Smith, A Garde, et al. The political economy of infant and young child feeding: confronting corporate power, overcoming structural barriers, and accelerating progress Lancet (2023) https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22) 019 33-X

31. K Uvnäs Moberg, A Ekström-Bergström, S Buckley, et al. Maternal plasma levels of oxytocin during breastfeeding—a systematic review PLoS One, 15 (2020), Article e023 5806

32. EM Miller Beyond passive immunity: breastfeeding, milk and collaborative mother-infant immune systems C Tomori, AEL Palmquist, EA Quinn (Eds.), Breastfeeding, Routledge, London (2018), pp. 26-39

33. KA Lackey, JE Williams, CL Meehan, et al. What’s normal? Microbiomes in human milk and infant feces are related to each other but vary geographically: the INSPIRE study Front Nutr, 6 (2019), p. 45

34. KG Peres, AM Cascaes, GG Nascimento, CG Victora Effect of breastfeeding on malocclusions: a systematic review and meta-analysis Acta Paediatr, 104 (2015), pp. 54-61

35. JE Williams, JM Carrothers, KA Lackey, et al. Strong multivariate relations exist among milk, oral, and fecal microbiomes in mother-infant dyads during the first six months postpartum J Nutr, 149 (2019), pp. 902-914

36. S Moossavi, S Sepehri, B Robertson, et al. Composition and variation of the human milk microbiota are influenced by maternal and early-life factors Cell host-microbe, 25 (2019), pp. 324-335

37. JHJ van Sadelhoff, D Mastorakou, H Weenen, B Stahl, J Garssen, A Hartog Differences in levels of free amino acids and total protein in human foremilk and hindmilk Nutrients, 10 (2018), Article 1828

38. K Christensson, C Siles, L Moreno, et al. Temperature, metabolic adaptation and crying in healthy full-term newborns cared for skin-to-skin or in a cot Acta Paediatr, 81 (1992), pp. 488-493

39. HL Ball, C Tomori, JJ McKenna Toward an integrated anthropology of infant sleep Am Anthropol, 121 (2019), pp. 595-612

40. A Klopp, L Vehling, AB Becker, et al. Modes of infant feeding and the risk of childhood asthma: a prospective birth cohort study J Pediatr, 190 (2017), pp. 192-199

41. R Li, SB Fein, LM Grummer-Strawn Do infants fed from bottles lack self-regulation of milk intake compared with directly breastfed infants? Pediatrics, 125 (2010), pp. e1386-e1393

42. P Van Esterik Beyond the breast-bottle controversy Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ (1989)

43. P Van Esterik, RA O’Connor The dance of nurture: negotiating infant feeding Berghahn Books, New York, NY (2017)

44. JL Fitzstevens, KC Smith, JI Hagadorn, MJ Caimano, AP Matson, EA Brownell Systematic review of the human milk microbiota Nutr Clin Pract, 32 (2017), pp. 354-364

45. K Pärnänen, A Karkman, J Hultman, et al. Maternal gut and breast milk microbiota affect infant gut antibiotic resistome and mobile genetic elements Nat Commun, 9 (2018), Article 3891

46. MI Zonneveld, MJC van Herwijnen, MM Fernandez-Gutierrez, et al. Human milk extracellular vesicles target nodes in interconnected signaling pathways that enhance oral epithelial barrier function and dampen immune responses J Extracell Vesicles, 10 (2021), Article e12071

47. MJ van Herwijnen, MI Zonneveld, S Goerdayal, et al. Comprehensive proteomic analysis of human milk-derived extracellular vesicles unveils a novel functional proteome distinct from other milk components Mol Cell Proteomics, 15 (2016), pp. 3412-3423

48. JM Rodríguez, L Fernández, V Verhasselt The gut–breast axis: programming health for life Nutrients, 13 (2021), p. 606

49. C Pisano, J Galley, M Elbahrawy, et al. Human breast milk-derived extracellular vesicles in the protection against experimental necrotizing enterocolitis J Pediatr Surg, 55 (2020), pp. 54-58

50. JHJ van Sadelhoff, BJM van de Heijning, B Stahl, et al. Longitudinal variation of amino acid levels in human milk and their associations with infant gender Nutrients, 10 (2018), Article 1233

51. JHJ van Sadelhoff, SP Wiertsema, J Garssen, A Hogenkamp Free amino acids in human milk: a potential role for glutamine and glutamate in the protection against neonatal allergies and infections Front Immunol, 11 (2020), Article 1007

52. ME Baldeón, F Zertuche, N Flores, M Fornasini Free amino acid content in human milk is associated with infant gender and weight gain during the first four months of lactation Nutrients, 11 (2019), Article 2239

53. AK Ventura, GK Beauchamp, JA Mennella Infant regulation of intake: the effect of free glutamate content in infant formulas Am J Clin Nutr, 95 (2012), pp. 875-881

54. A Larnkjær, S Bruun, D Pedersen, et al. Free amino acids in human milk and Associations with maternal anthropometry and infant growth J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 63 (2016), pp. 374-378

55. JHJ van Sadelhoff, LP Siziba, L Buchenauer, et al. Free and total amino acids in human milk in relation to maternal and infant characteristics and infant health outcomes: the Ulm SPATZ Health Study Nutrients, 13 (2021), Article 2009

56. O Cabanillas-Bernal, K Cervantes-Luevano, GI Flores-Acosta, J Bernáldez-Sarabia, AF Licea-Navarro COVID-19 neutralizing antibodies in the breast milk of mothers vaccinated with three different vaccines in Mexico Vaccines, 10 (2022), p. 629

57. V Narayanaswamy, BT Pentecost, CN Schoen, et al. Neutralizing antibodies and cytokines in breast milk after coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) mRNA vaccination Obstet Gynecol, 139 (2022), pp. 181-191

58. SH Perl, A Uzan-Yulzari, H Klainer, et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies in breast milk after COVID-19 vaccination of breastfeeding women JAMA, 325 (2021), pp. 2013-2014

59. BE Young, AE Seppo, N Diaz, et al. Association of human milk antibody induction, persistence, and neutralizing capacity with SARS-CoV-2 infection vs mRNA vaccination JAMA Pediatr, 176 (2021), pp. 159-168

60. PAR Neves, JS Vaz, FS Maia, et al. Rates and time trends in the consumption of breastmilk, formula, and animal milk by children younger than 2 years from 2000 to 2019: analysis of 113 countries Lancet Child Adolesc Health, 5 (2021), pp. 619-630

61. PAR Neves, JS Vaz, LIC Ricardo, et al. Disparities in early initiation of breastfeeding and pre-lacteal feeding: a study of low- and middle-income countries Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol, 36 (2022), pp. 741-749

62. R Pérez-Escamilla, A Hromi-Fiedler, EC Rhodes, et al. Impact of pre-lacteal feeds and neonatal introduction of breast milk substitutes on breast-feeding outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis Matern Child Nutr, 18 (suppl 3) (2022), Article e13368

63. M Ekholuenetale, A Barrow What do early initiation and duration of breastfeeding have to do with childhood mortality? Analysis of pooled population-based data in 35 sub-Saharan African countries Int Breastfeed J, 16 (2021), p. 91

64. CS Boccolini, ML Carvalho, MI Oliveira, R Pérez-Escamilla Breastfeeding during the first hour of life and neonatal mortality J Pediatr (Rio J), 89 (2013), pp. 131-136

65. R Pérez-Escamilla, GS Buccini, S Segura-Pérez, E Piwoz Perspective: should exclusive breastfeeding still be recommended for 6 months? Adv Nutr, 10 (2019), pp. 931-943

66. V Khanal, M Adhikari, K Sauer, Y Zhao Factors associated with the introduction of pre-lacteal feeds in Nepal: findings from the Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2011 Int Breastfeed J, 8 (2013), p. 9

67. NL Rogers, J Abdi, D Moore, et al. Colostrum avoidance, pre-lacteal feeding and late breast-feeding initiation in rural Northern Ethiopia Public Health Nutr, 14 (2011), pp. 2029-2036

68. KM McKenna, RT Shankar The practice of pre-lacteal feeding to newborns among Hindu and Muslim families J Midwifery Womens Health, 54 (2009), pp. 78-81

69. AS Goldman Modulation of the gastrointestinal tract of infants by human milk. Interfaces and interactions. An evolutionary perspective J Nutr, 130 (suppl 2) (2000), pp. 426S-431S

70. G Ray, S Singh Prevailing practices and beliefs related to breastfeeding and top feeding in an urban slum community of Varanasi Indian J Prev Soc Med, 28 (1997), pp. 37-45

71. R Pérez-Escamilla, S Segura-Millán, J Canahuati, H Allen Pre-lacteal feeds are negatively associated with breast-feeding outcomes in Honduras J Nutr, 126 (1996), pp. 2765-2773

72. S Segura-Pérez, L Richter, EC Rhodes, et al. Risk factors for self-reported insufficient milk during the first 6 months of life: a systematic review Matern Child Nutr, 18 (suppl 3) (2022), Article e13353

73. M Boban, I Zakarija-Grković In-hospital formula supplementation of healthy newborns: practices, reasons, and their medical justification Breastfeed Med, 11 (2016), pp. 448-454

74. T Nguyen, BA Dennison, W Fan, C Xu, GS Birkhead Variation in formula supplementation of breastfed newborn infants in New York hospitals Pediatrics, 140 (2017), Article e20170142

75. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention mPINC 2020 national results report Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA (2020)

76. MJ Netting, NA Moumin, EJ Knight, RK Golley, M Makrides, TJ Green The Australian Feeding Infants and Toddler Study (OzFITS 2021): breastfeeding and early feeding practices Nutrients, 14 (2022), p. 206

77. KR Rosenberg The evolution of human infancy: why it helps to be helpless Annu Rev Anthropol, 50 (2021), pp. 423-440

78. F Cook, F Mensah, JK Bayer, H Hiscock Prevalence, comorbidity and factors associated with sleeping, crying and feeding problems at 1 month of age: a community-based survey J Paediatr Child Health, 55 (2019), pp. 644-651

79. BW Forsyth, JM Leventhal, PL McCarthy Mothers’ perceptions of problems of feeding and crying behaviors. A prospective study Am J Dis Child, 139 (1985), pp. 269-272

80. LM Mohebati, P Hilpert, S Bath, et al. Perceived insufficient milk among primiparous, fully breastfeeding women: is infant crying important? Matern Child Nutr, 17 (2021), Article e13133

81. M Vilar-Compte, R Pérez-Escamilla, D Orta, et al. Impact of baby behavior on caregiver’s infant feeding decisions during the first 6 months of life: a systematic review Matern Child Nutr, 18 (2022), Article e13345

82. L Gilkerson, T Burkhardt, LE Katch, SL Hans Increasing parenting self-efficacy: the Fussy Baby Network intervention Infant Ment Health J, 41 (2020), pp. 232-245

83. SP Nelson, EH Chen, GM Syniar, KK Christoffel Prevalence of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux during infancy. A pediatric practice-based survey Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med, 151 (1997), pp. 569-572

84. D Wolke, A Bilgin, M Samara Systematic review and meta-analysis: fussing and crying durations and prevalence of colic in infants J Pediatr, 185 (2017), pp. 55-61

85. IS James-Roberts, S Conroy, J Hurry Links between infant crying and sleep-waking at six weeks of age Early Hum Dev, 48 (1997), pp. 143-152

86. B Hudson, A Alderton, C Doocey, D Nicholson, L Toop, AS Day Crying and spilling—time to stop the over-medicalisation of normal infant behaviour N Z Med J, 125 (2012), pp. 119-126

87. SB Freedman, N Al-Harthy, J Thull-Freedman The crying infant: diagnostic testing and frequency of serious underlying disease Pediatrics, 123 (2009), pp. 841-848

88. PS Douglas, PS Hill The crying baby: what approach? Curr Opin Pediatr, 23 (2011), pp. 523-529

89. J Zeevenhooven, PD Browne, MP L’Hoir, C de Weerth, MA Benninga Infant colic: mechanisms and management Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 15 (2018), pp. 479-496

90. MR Elliott, SM Reilly, J Drummond, N Letourneau The effect of different soothing interventions on infant crying and on parent-infant interaction Infant Ment Health J, 23 (2002), pp. 310-328

91. EL Möller, W de Vente, R Rodenburg Infant crying and the calming response: parental versus mechanical soothing using swaddling, sound, and movement PLoS One, 14 (2019), Article e0214548

92. CR Howard, N Lanphear, BP Lanphear, S Eberly, RA Lawrence Parental responses to infant crying and colic: the effect on breastfeeding duration Breastfeed Med, 1 (2006), pp. 146-155

93. MG Corbo, G Mansi, A Stagni, et al. Nonnutritive sucking during heel stick procedures decreases behavioral distress in the newborn infant Biol Neonate, 77 (2000), pp. 162-167

94. D Munblit, H Crawley, R Hyde, RJ Boyle Health and nutrition claims for infant formula are poorly substantiated and potentially harmful BMJ, 369 (2020), p. m875

95. HI Allen, U Pendower, M Santer, et al. Detection and management of milk allergy: Delphi consensus study Clin Exp Allergy, 52 (2022), pp. 848-858

96. JD Gussler, LH Briesemeister The insufficient milk syndrome: a biocultural explanation Med Anthropol, 4 (1980), pp. 145-174

97. P Baker, K Russ, M Kang, et al. Globalization, first-foods systems transformations, and corporate power: a synthesis of literature and data on the market and political practices of the transnational baby food industry Global Health, 17 (2021), p. 58

98. G Hastings, K Angus, D Eadie, K Hunt Selling second best: how infant formula marketing works Global Health, 16 (2020), p. 77

99. EG Piwoz, SL Huffman The impact of marketing of breast-milk substitutes on WHO-recommended breast-feeding practices Food Nutr Bull, 36 (2015), pp. 373-386

100.PD Hill, SS Humenick Insufficient milk supply Image J Nurs Sch, 21 (1989), pp. 145-148

101. Y Huang, Y Liu, XY Yu, TY Zeng The rates and factors of perceived insufficient milk supply: a systematic review Matern Child Nutr, 18 (2022), Article e13255

102. L Gatti Maternal perceptions of insufficient milk supply in breast-feeding J Nurs Scholarsh, 40 (2008), pp. 355-363

103.PF Belamarich, RE Bochner, AD Racine A critical review of the marketing claims of infant formula products in the United States Clin Pediatr, 55 (2016), pp. 437-442

104. D Karall, JP Ndayisaba, A Heichlinger, et al. Breast-feeding duration: early weaning-do we sufficiently consider the risk factors? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 61 (2015), pp. 577-582

105.M Boss, P Hartmann How breastfeeding works: anatomy and physiology of human lactation G Larsson, M Larsson (Eds.), Breastfeeding and breast milk— from biochemistry to impact, Thieme, Stuttgart (2018), pp. 39-77

106.UNICEF, WHO Implementation guidance on counseling women to improve breastfeeding practices United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund, New York, NY (2021)

107.WHO Guideline: counseling of women to improve breastfeeding practices World Health Organization, Geneva (2018)

108. C Tomori, S Hernández-Cordero, N Busath, P Menon, R Pérez-Escamilla What works to protect, promote and support breastfeeding on a large scale: a review of reviews Matern Child Nutr, 18 (suppl 3) (2022), Article e13344

109.A Nandi, D Jahagirdar, MC Dimitris, et al. The impact of parental and medical leave policies on socio-economic and health outcomes in OECD countries: a systematic review of the empirical literature Milbank Q, 96 (2018), pp. 434-471

110. E Andres Maternity leave utilization and its relationship to postpartum maternal and child health outcomes BA dissertation The George Washington University (2015), p. 77

111. MR Jiménez-Mérida, M Romero-Saldaña, R Molina-Luque, et al. Women-centered workplace health promotion interventions: a systematic review Int Nurs Rev, 68 (2020), pp. 90-98

112. X Tang, P Patterson, K MacKenzie-Shalders, et al. Workplace programmes for supporting breast-feeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis Public Health Nutr, 24 (2021), pp. 1501-1513

113. International Labour Organization Building forward fairer: women’s rights to work and at work at the core of the COVID-19 recovery International Labour Organization, Geneva (2021)

114. M Vilar-Compte, G Teruel, D Flores, GJ Carroll, GS Buccini, R Pérez-Escamilla Costing a maternity leave cash transfer to support breastfeeding among informally employed Mexican women Food Nutr Bull, 40 (2019), pp. 171-181

115. AYM Siregar, P Pitriyan, D Hardiawan, et al. The yearly financing need of providing paid maternity leave in the informal sector in Indonesia Int Breastfeed J, 16 (2021), p. 17

116. FZ Karimi, HH Miri, T Khadivzadeh, N Maleki-Saghooni The effect of mother-infant skin-to-skin contact immediately after birth on exclusive breastfeeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc, 21 (2020), pp. 46-56

117. AG Mekonnen, SS Yehualashet, AD Bayleyegn The effects of kangaroo mother care on the time to breastfeeding initiation among preterm and LBW infants: a meta-analysis of published studies Int Breastfeed J, 14 (2019), p. 12

118. EO Boundy, R Dastjerdi, D Spiegelman, et al. Kangaroo mother care and neonatal outcomes: a meta-analysis Pediatrics, 137 (2016), Article e20152238

119. NR van Veenendaal, WH Heideman, J Limpens, et al. Hospitalising preterm infants in single-family rooms versus open bay units: a systematic review and meta-analysis Lancet Child Adolesc Health, 3 (2019), pp. 147-157

120. A Flint, K New, MW Davies Cup feeding versus other forms of supplemental enteral feeding for newborn infants unable to fully breastfeed Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 8 (2016), Article CD005092

121. J Cartwright, T Atz, S Newman, M Mueller, JR Demirci Integrative review of interventions to promote breastfeeding in the late preterm infant J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs, 46 (2017), pp. 347-356

122. FJ Fair, A Morrison, H Soltani The impact of baby-friendly initiative accreditation: an overview of systematic reviews Matern Child Nutr, 17 (2021), Article e13216

123. VM Fallon, JA Harrold, A Chisholm The impact of the UK baby friendly initiative on maternal and infant health outcomes: a mixed-methods systematic review Matern Child Nutr, 15 (2019), Article e12778

124. C Feltner, RP Weber, A Stuebe, CA Grodensky, C Orr, M Viswanathan Breastfeeding programs and policies, breastfeeding uptake, and maternal health outcomes in developed countries Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD (2018)

125. K Wouk, KP Tully, MH Labbok Systematic review of evidence for baby-friendly hospital initiative step 3 J Hum Lact, 33 (2017), pp. 50-82

126. R Pérez-Escamilla, L Curry, D Minhas, L Taylor, E Bradley Scaling up of breastfeeding promotion programs in low- and middle-income countries: the “breastfeeding gear” model Adv Nutr, 3 (2012), pp. 790-800

127. I Dall’Oglio, F Marchetti, R Mascolo, et al. Breastfeeding protection, promotion, and support in humanitarian emergencies: a systematic review of literature J Hum Lact, 36 (2020) 89033441 9900151

128. R Rana, M McGrath, E Sharma, P Gupta, M Kerac Effectiveness of breastfeeding support packages in low- and middle-income countries for infants under six months: a systematic review Nutrients, 13 (2021), p. 681