Wataru Sano, Daizen Hirata, Akira Teramoto, Mineo Iwatate, Santa Hattori, Mikio Fujita, and Yasushi Sano

Contributor Information

Wataru Sano, Gastrointestinal Center, Sano Hospital, Hyogo 655-0031, Japan. pj.oc.oohay@onasataw.

Daizen Hirata, Gastrointestinal Center, Sano Hospital, Hyogo 655-0031, Japan.

Akira Teramoto, Gastrointestinal Center, Sano Hospital, Hyogo 655-0031, Japan.

Mineo Iwatate, Gastrointestinal Center, Sano Hospital, Hyogo 655-0031, Japan.

Santa Hattori, Gastrointestinal Center, Sano Hospital, Hyogo 655-0031, Japan.

Mikio Fujita, Gastrointestinal Center, Sano Hospital, Hyogo 655-0031, Japan.

Yasushi Sano, Gastrointestinal Center, Sano Hospital, Hyogo 655-0031, Japan.

Abstract

In recent years, the serrated neoplasia pathway where serrated polyps arise as colorectal cancer has gained considerable attention as a new carcinogenic pathway. Colorectal serrated polyps are histopathologically classified into hyperplastic polyps (Hps), sessile serrated lesions, and traditional serrated adenomas; in the serrated neoplasia pathway, the latter two are considered to be premalignant. In western countries, all colorectal polyps, including serrated polyps, apart from diminutive rectosigmoid HPs are removed. However, in Asian countries, the treatment strategy for colorectal serrated polyps has remained unestablished. Therefore, in this review, we described the clinicopathological features of colorectal serrated polyps and proposed to remove HPs and sessile serrated lesions ≥ 6 mm in size, and traditional serrated adenomas of any size.

Keywords: Hyperplastic polyp, Sessile serrated adenoma/polyp, Sessile serrated lesion, Traditional serrated adenoma, Cytological dysplasia, Cryptal dysplasia Core tip: In western countries, generally all colorectal polyps are removed, including serrated polyps, except rectosigmoid hyperplastic polyps ≤ 5 mm in size. However, no treatment strategy has been developed for colorectal serrated polyps in Asian countries. Hence, in this review, we described the clinicopathological features of colorectal serrated polyps and proposed to remove hyperplastic polyps and sessile serrated lesions ≥ 6 mm in size, and traditional serrated adenomas of any size by narrow-band imaging observation.

INTRODUCTION

Apart from adenoma-carcinoma sequence and de novo carcinogenic pathways1,2, the serrated neoplasia pathway where serrated polyps emerge as colorectal cancer has been recently gaining considerable research interest as a new carcinogenic pathway. Hyperplastic polyps (HPs), sessile serrated lesions (SSLs), and traditional serrated adenomas (TSAs) are the histopathological classifications of colorectal serrated polyps3. Of these, SSLs and TSAs are regarded as premalignant lesions in the serrated neoplasia pathway.

SSLs had been previously described as sessile serrated adenoma/polyps4. They possess molecular features, such as hypermethylation of the CpG islands in the promoter regions of tumour suppressor genes (i.e., the CpG island methylator phenotype-high: CIMP-high) and BRAF mutations, and they progress to either of the following colorectal cancer types: (1) Microsatellite unstable colorectal cancers with MLH1 inactivation; or (2) Microsatellite stable colorectal cancers without MLH1 inactivation. Meanwhile, TSAs progress to microsatellite stable colorectal cancers through the following molecular features: (1) CIMP-high and BRAF mutations without MLH1 inactivation; or (2) KRAS mutations without any of the CIMP-high, BRAF mutations, or MLH1 inactivation1-3,5-7.

Generally, western countries remove all colorectal polyps, including serrated polyps, apart from rectosigmoid HPs ≤ 5 mm in size. Unfortunately, Asian countries still have no treatment strategy for colorectal serrated polyps. Hence, in this review, we described the clinicopathological features of colorectal serrated polyps and proposed a treatment strategy for them.

PREVALENCE OF COLORECTAL SERRATED POLYPS

To clarify the prevalence of colorectal serrated polyps, particularly SSLs, we conducted a prospective study8. Between June 2013 and May 2014, patients aged ≥ 40 years undergoing colonoscopy for standard clinical indications at our centre were prospectively enrolled. During a colonoscopy, 0.05% indigo carmine dye was sprayed throughout the colorectum by using the waterjet function to highlight the lesions. All detected lesions were diagnosed by high-definition magnifying narrow-band imaging (NBI) and were removed endoscopically or surgically, aside from rectosigmoid NICE (NBI international colorectal endoscopic)9,10 or JNET (Japan NBI Expert Team)11 type 1 lesions ≤ 5 mm in size. Regarding rectosigmoid NICE or JNET type 1 lesions measuring ≤ 5 mm, we recorded their total number by using the tally counter and then removed some of them. In 315 out of 343 eligible patients, 1301 colorectal lesions were removed endoscopically or surgically. Of them, 165 HPs in 97 patients, 21 SSLs in 17 patients, and 13 TSAs in 12 patients were identified histopathologically. Furthermore, the prevalence of HPs, SSLs, and TSAs, defined as the proportion of patients with ≥ 1 HP, SSL, and TSA lesions, was 28.3%, 5.0%, and 3.5%, respectively.

In the study of Hazewinkel et al12 of 1426 patients with a median age of 60 years who underwent screening colonoscopy, the prevalence of HPs, SSLs, and TSAs was 23.8%, 4.8%, and 0.1%, respectively. In another study of 1479 patients by Carr et al13, the prevalence of HPs, SSLs, and TSAs was 30%, 3.9%, and 0.7%, respectively. Abdeljawad et al14 reported that the prevalence of SSLs was 8.1% in their study of 1910 patients aged ≥ 50 years who underwent screening colonoscopy. The previously reported prevalence of colorectal serrated polyps varies due to the study design and population, colonoscopy equipment and observation method, the experience of the endoscopists, and the histopathological diagnostic criteria. However, SSLs, which have recently attracted attention as precursors of microsatellite unstable colorectal cancers, seem not to be rare in clinical practice14,15.

ENDOSCOPIC FEATURES OF COLORECTAL SERRATED POLYPS

HP

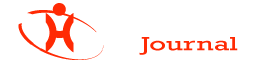

Hps commonly exist in the left colorectum, particularly the rectosigmoid colon, and are often ≤ 5 mm in size. In white light endoscopy, they appear as discoloured, flat elevated lesions (Figure 1A). In NBI endoscopy, they appear as whitish lesions (NICE or JNET type 1) without expanded, brown meshed capillary vessels (MC vessels)16, which are seen in conventional adenomas (Figure 1 B). In chromoendoscopy, Kudo type II asteroid pits are observed on the lesion surface (Figure 1C).

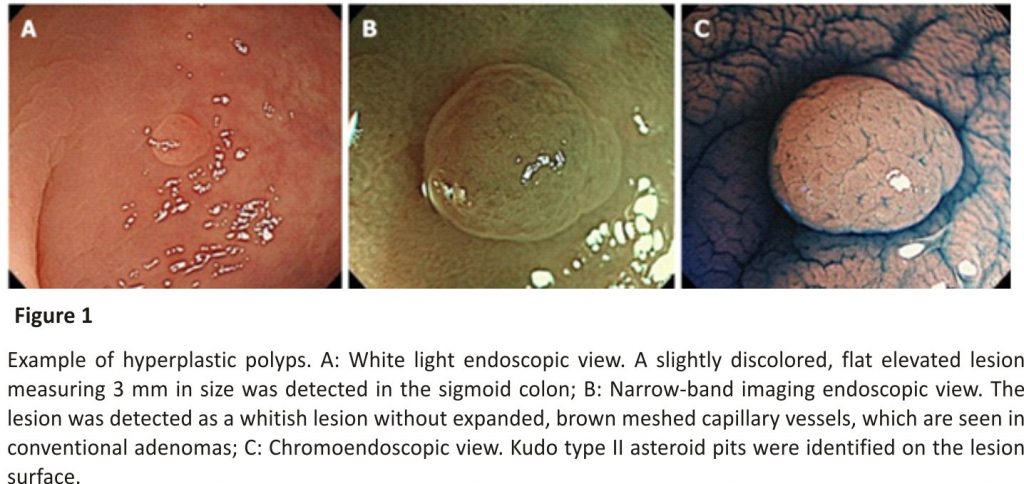

SSLs typically occur in the right colon and are slightly larger than HPs. The characteristic findings of SSLs include various endoscopic findings, such as a mucous cap in white light endoscopy17, a red cap sign in NBI endoscopy18, a cloud-like surface in white light or NBI endoscopy19, dilated and branching vessels in NBI endoscopy20, expanded crypt openings in NBI endoscopy21, and type II open-shape (type II-O) pits in chromoendoscopy22 (Figure 2). However, SSLs resemble HPs endoscopically, and most of them are detected as discoloured, flat elevated lesions in white light endoscopy and whitish lesions (NICE or JNET type 1) in NBI endoscopy; therefore, differentiating between HPs and SSLs endoscopically in clinical practice remains often challenging.

SSL with dysplasia

SSL is generally accompanied by dysplasia during carcinogenesis1-4,6. Endoscopic morphological findings, such as large or small nodules on the surface and partial protrusion of SSLs, were useful indicators of dysplasia within SSLs, with an accuracy of 93.3% on the analysis of 326 SSLs (Figure 3)23. Burgess et al24 also reported that the presence of any 0-Is or nodular components within SSLs was associated with dysplasia within SSLs, with 71.0% accuracy on the analysis of 207 SSLs ≥ 20 mm in size.

Regarding the pit pattern analysis of SSLs with dysplasia (SSLDs) using magnifying chromoendoscopy, Burgess et al24 stated that SSLDs exhibited an adenomatous pit pattern (Kudo type III, IV, or V), with 70.6% accuracy on the analysis of 201 SSLs ≥ 20 mm in size. Moreover, Murakami et al25 reported that SSLDs exhibited Kudo type III, IV, VI, or VN pit patterns in addition to a type II pit pattern, with 99.4% accuracy on the analysis of 314 SSLs. Tanaka et al26 also described that SSLDs exhibited an adenomatous pit pattern (Kudo type III or IV) in addition to a type II or II-O pit pattern, with 89.4% accuracy on the analysis of 123 SSLs. Utilizing non-magnifying NBI observation, Tate et al27reported that a demarcated area with a neoplastic pit pattern (Kudo type III/IV or NICE type 2) was a useful indicator of dysplasia within SSLs, with 95.0% accuracy on the analysis of 141 SSLs ≥ 8 mm in size.

Thus, high-accuracy endoscopic diagnosis of SSLDs is becoming possible; however, some SSLDs do not exhibit the above mentioned characteristic endoscopic findings.

TSA

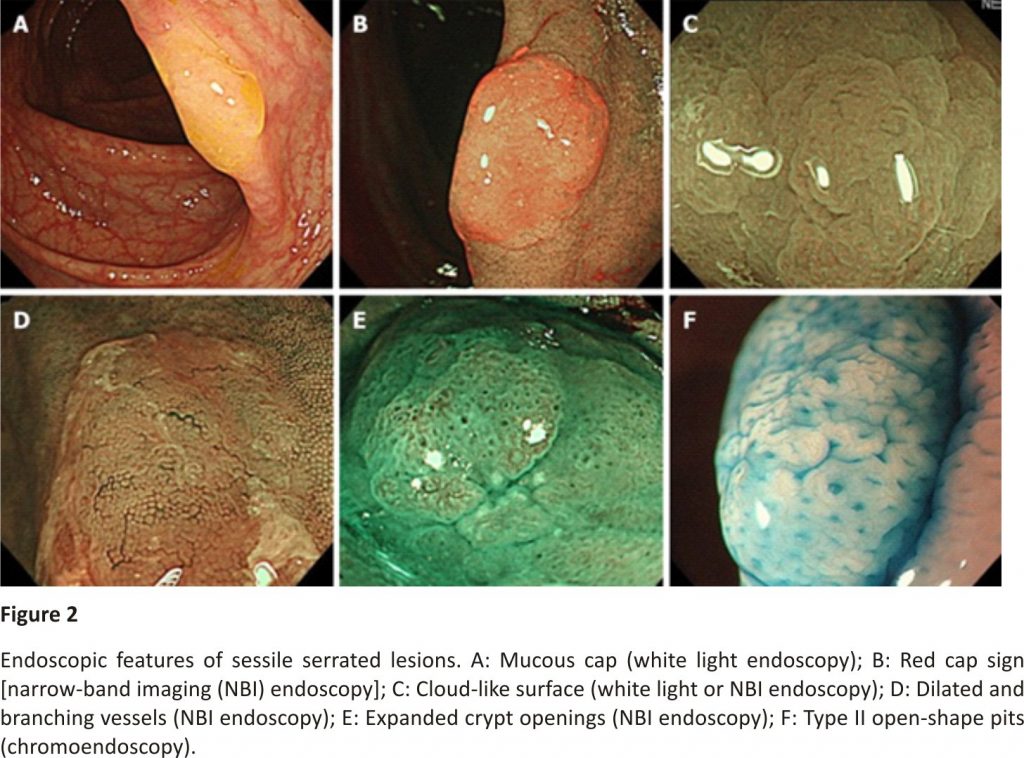

TSAs commonly appear in the left colorectum, similar to HPs. They appear as reddish, protruded or pedunculated lesions in white light observation and “pine cone-like” or “branch coral-like” lesions in macroscopic observation (Figure 4A and B). In NBI endoscopy, “leaf vein-like” expanded, brown capillary vessels, which differ from MC vessels seen in conventional adenomas, are identified in the large stromal area around the crypts, and TSAs appear as brownish resembling conventional adenomas (NICE or JNET type 2) (Figure 4C). In chromoendoscopy, they are characterized by type IIIH pits, which are Kudo type IIIL-like tubular pits accompanied with serration in the crypt margin, or type IVH pits, which are Kudo type IV-like villous pits accompanied with serration in the crypt margin (Figure 4D)28.

HISTOPATHOLOGICAL FEATURES OF COLORECTAL SERRATED POLYPS

HP

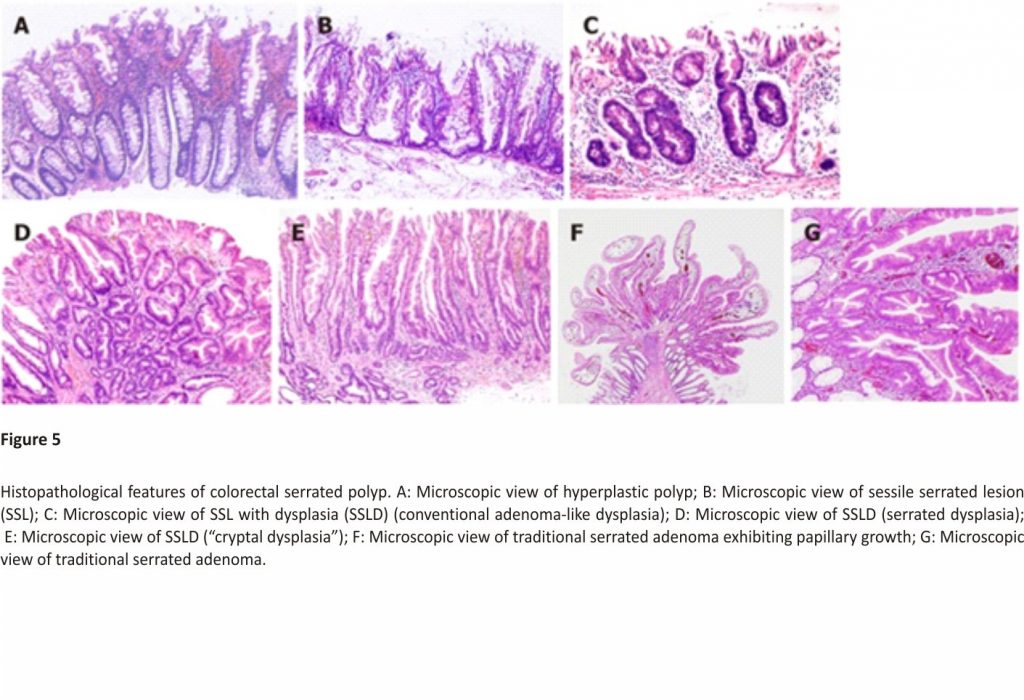

On the basis of mucin-type, HPs are subclassified into three types, namely, microvesicular HPs (MVHPs), goblet-cell-rich HPs, and mucin-poor HPs2. MVHPs and goblet-cell-rich HPs account for up to 60% and 30%, respectively, whereas mucin-poor HPs remain rare. All these HPs are histologically characterized by the elongation of the intestinal crypts, with serration of the upper part of the crypts (Figure 5A). Conversely, the lower part of the crypts is narrow, without any serration. The basal part of the crypts exhibits uniform proliferation. Meanwhile, cytological dysplasia is not seen in any HP types.

SSLs are histopathologically characterized by (1) crypt dilation; (2) irregularly branching crypts; and (3) horizontally arranged basal crypts (inverted T- and/or L-shaped crypts) (Figure 5B)29,30. The proliferation zone of the crypts often shifts from the basal part to the side of the crypts2.

According to the Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum criteria established in 2011, when at least two of these three histopathological findings were found in ≥ 10% of the lesion area, the serrated polyps are diagnosed as SSLs29,30. However, those that do not meet the above-mentioned criteria are diagnosed as HPs.

SSLD

Generally, cytological dysplasia arising in SSLs is divided into two types, namely, conventional adenoma-like dysplasia and serrated dysplasia (Figure 5C and D)3,4,31,32.

Conventional adenoma-like dysplasia is histopathologically characterized by the presence of elongated cells with penicillate and hyperchromatic pseudostratified nuclei, basophilic cytoplasm, and increased mitoses, and it resembles a conventional tubular or tubulovillous adenoma cytologically. Meanwhile, serrated dysplasia is histopathologically characterized by a proliferation of cuboidal atypical cells, eosinophilic cytoplasm, enlarged round nuclei with open vesicular prominent chromatin, prominent nucleoli, and increased mitoses3,4,31,32.

After the analysis of 326 SSLs, we also found a previously unreported type of dysplasia, termed “cryptal dysplasia,” which is localized in the crypt base but cannot be classified as either conventional adenoma-like or serrated dysplasia (Figure 5E)23. Although the clinical significance of “cryptal dysplasia” remains unclear, this type was common within SSLDs and mostly coexisted with conventional adenoma-like and/or serrated dysplasia to a varied extent. Further assessment of the clinical significance of “cryptal dysplasia” is necessary to become widely recognized and be applied by endoscopists and pathologists in their diagnostic examinations.

TSA

TSAs are histopathologically characterized by tubulovillous or villous architecture, tall columnar cells with intensely eosinophilic cytoplasm and pencillate nuclei, slit-like serrations due to narrow slits in the deeply eosinophilic epithelium resembling normal small intestinal mucosa, and ectopic crypt formations due to the abnormal crypt development with loss of orientation toward the muscularis mucosae (Figure 5F and G)3,7.

MANAGEMENT OF COLORECTAL SERRATED POLYPS

NICE or JNET type 1 lesions including HP and SSL

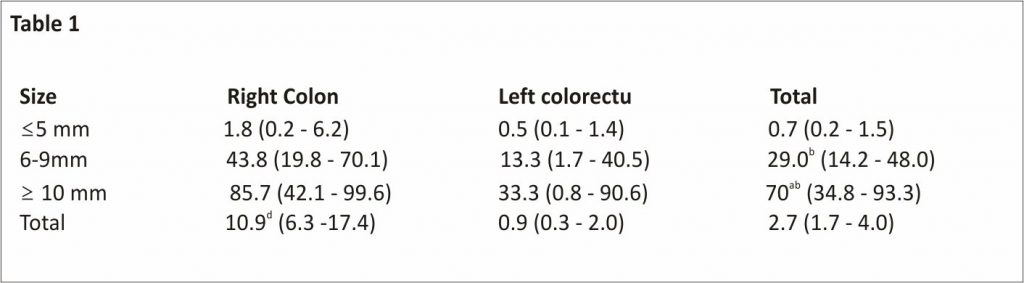

NBI observation detects both HPs and SSLs as NICE or JNET type 1 lesions. In our study, the probability of NICE or JNET type 1 lesions being SSLs significantly increased with the lesion size, with 6 mm as the boundary (≤ 5 mm: 0.7%; 6-9 mm: 29.0%; ≥ 10 mm: 70%) (Table11)8. In addition, 89.1% and 10.9% of HPs were ≤ 5 and ≥ 6 mm in size, respectively, showing a pyramid-type distribution; meanwhile, 76.2% and 23.8% of SSLs were ≥ 6 and ≤ 5 mm in size, respectively, indicating an inverted pyramid-type distribution. Furthermore, HPs, particularly MVHPs, harbour genetic abnormalities, such as CIMP-high and BRAF mutations, similar to SSLs33-35. Thus, HPs will transition to SSLs with an increase of the lesion size, with a boundary of approximately 6 mm.

Table 1

Probability of narrow-band imaging international colorectal endoscopic or Japan narrow-band imaging expert team type 1 lesions being sessile serrated lesions, % (95%CI)

We histopathologically analyzed 792 narrow-band imaging international colorectal endoscopic or Japan narrow-band imaging expert team type 1 lesions. The overall probability of narrow-band imaging international colorectal endoscopic or Japan narrow-band imaging expert team type 1 lesions being sessile serrated lesions was 2.7% (21/792). This probability significantly increased as the lesion size also increased (≤ 5 mm: 0.7%; 6-9 mm: 29.0%; ≥ 10 mm: 70%) and was significantly higher in the right colon than in the left colorectum (10.9% vs 0.9%).

aP < 0.05 vs 6-9 mm,

bP < 0.01 vs ≤ 5 mm, and

dP < 0.01 vs left colorectum, the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test.

If differentiating between HPs and SSLs is easy, SSLs can be removed selectively; however, it is often challenging in clinical practice. In addition, NICE or JNET type 1 lesion ≥ 6 mm in size, even if HPs, may eventually transition to SSLs if left unattended. Therefore, we propose to remove all NICE or JNET type 1 lesions ≥ 6 mm in size. In our study, most NICE or JNET type 1 lesions were ≤ 5 mm, and only 1.1% of them were ≥ 6 mm in size8. Additionally, the prevalence of NICE or JNET type 1 lesions ≥ 6 mm in size was not high at 8.5%, suggesting that the removal of all NICE or JNET type 1 lesions ≥ 6 mm in size seems feasible in clinical practice.

Meanwhile, in our study, the probability of NICE or JNET type 1 lesions ≤ 5 mm in size being SSLs was only 0.7% (Table11)8. In our other study, the rate of dysplasia within SSLs increased as the lesion size increased (≤ 5 mm, 0%; 6-9 mm, 6.0%; ≥ 10 mm, 13.6%) (Table 2)23, similar to a stepwise increase of the dysplasia degree or cancer rate within conventional adenomas that occurs along with an increase in lesion size36-38. Thus, the probability of NICE or JNET type 1 lesions ≤ 5 mm in size being SSLs was extremely low, and even if they are SSLs, the rate of dysplasia within SSLs ≤ 5 mm in size was also extremely low, suggesting that NICE or JNET type 1 lesions ≤ 5 mm in size can be left in situ.

We histopathologically analyzed 326 sessile serrated lesions. The overall rate of dysplasia (conventional adenoma-like dysplasia and/or serrated dysplasia) within sessile serrated lesions was 8.0% (26/326). This rate significantly increased as the lesion size increased (≤ 5 mm: 0%; 6-9 mm: 6.0%; ≥ 10 mm: 13.6%) but exhibited no significant difference between the right colon and left colorectum.

aP < 0.05 vs ≤ 5 mm,

bP < 0.01 vs ≤ 5 mm, and

cP < 0.05 vs 6-9 mm, the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test.

Western countries remove all NICE or JNET type 1 lesions ≤ 5 mm in the cecum, ascending, transverse, and descending colon. However, in our study, despite the relatively high (25.1%) prevalence of these lesions, the probability of these being SSLs was quite low (1.6%)8. Therefore, removing all NICE / JNET type 1 lesions ≤ 5 mm in the whole colon apart from the rectosigmoid colon appears to have more disadvantages such as the probable adverse events including post-polypectomy bleeding and perforation, the burden on the endoscopists, and the time-consuming examinations, than the advantages of removing SSLs ≤ 5 mm in size. However, these lesions include HPs, which have the potential to transition to SSLs, and some SSLs. Hence, we recommend following up these lesions at appropriate intervals (e.g., 5 years39,40) if left unattended.

SSLD

As mentioned, SSLs are frequently accompanied with dysplasia during carcinogenesis1-4,6, and they may rapidly progress to carcinomas after they start to develop dysplasia within them41. In our study, the rate of dysplasia within SSLs increased as the lesion size also increased, and all SSLDs were ≥ 6 mm in size (Table (Table22)23. Therefore, if all SSLs ≥ 6 mm in size are removed, we could possibly remove almost all SSLDs with high sensitivity. Given that endoscopically diagnosing SSLDs with high accuracy is gradually becoming possible23-27, colorectal lesions suspected of SSLDs should be removed en bloc for accurate pathological assessment and prevention of recurrent cancers due to incomplete removal.

TSA

In NBI endoscopy, TSAs are detected as NICE or JNET type 2 brownish lesions similar to conventional adenomas. Considering the lower prevalence8,12,13 and similar malignant potential42,43 (e.g., cancer rate within the lesions) of TSAs compared with conventional adenomas, we propose to remove all TSAs of any size in the same fashion as conventional adenomas.

CONCLUSION

In this review, we described the clinicopathological features of colorectal serrated polyps and proposed a treatment strategy for them. When the removal of all conventional adenomas and cancers, which exhibit NICE or JNET types 2 and 3 on NBI observation, is added to our proposed treatment strategy, the treatment algorithm for colorectal polyps, including serrated polyps, using NBI observation is as follows (Figure 6): (1) Leave in situ NICE or JNET type 1 lesions, such as HPs and few SSLs, at ≤ 5 mm in size, (2) Remove NICE or JNET type 1 lesions, such as HPs and SSLs, at ≥ 6 mm in size, and (3) Remove NICE or JNET types 2 and 3 lesions, including SSLDs, TSAs, conventional adenomas, and cancers, of any size. This treatment algorithm for colorectal polyps is simple and seems feasible in clinical practice. We believe that this simple treatment strategy will result in the decline of colorectal cancer morbidity and mortality in Asian countries.

LIMITATION

Our proposal of the treatment strategy for colorectal serrated polyps has the limitation that it is mainly based on studies of Japanese patients. Therefore, further studies are needed to evaluate the applicability of our treatment strategy in other Asian countries. We hope that in the future, treatment guidelines for colorectal serrated polyps will be established also in Asian countries, as well as surveillance guidelines based on these.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Dr. Kazuhito Ichikawa for capturing the histopathological pictures as well as Dr. Takahiro Fujimori for his useful advice regarding histopathological assessment.

References

1. Leggett B, Whitehall V. Role of the serrated pathway in colorectal cancer pathogenesis. Gastroenterology.2010; 138:2088– 2100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. IJspeert JE, Vermeulen L, Meijer GA, Dekker E. Serrated neoplasia-role in colorectal carcinogenesis and clinical implications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12: 401–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Pai RK, Mäkinen MJ, Rosty C. Colorectal serrated lesions and polyps. In: Nagtegaal ID, Arends MJ, Odze RD, Lam AK. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. Lyon: IARC Press, 2019: 163-169. [Google Scholar]

4. Snover DC, Ahnen DJ, Burt RW, Odze RD. Serrated polyps of the colon and rectum and serrated polyposis. In: Nagtegaal ID, Arends MJ, Odze RD, Lam AK. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. Lyon: IARC Press, 2010: 160-165. [Google Scholar]

5. Gaiser T, Meinhardt S, Hirsch D, Killian JK, Gaedcke J, Jo P, Ponsa I, Miró R, Rüschoff J, Seitz G, Hu Y, Camps J, Ried T. Molecular patterns in the evolution of serrated lesion of the colorectum. Int J Cancer. 2013;132: 1800–1810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Murakami T, Akazawa Y, Yatagai N, Hiromoto T, Sasahara N, Saito T, Sakamoto N, Nagahara A, Yao T. Molecular characterization of sessile serrated adenoma/polyps with dysplasia /carcinoma based on immunohistochemistry, next-generation sequencing, and microsatellite instability testing: a case series study. Diagn Pathol.2018; 13:88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. McCarthy AJ, Serra S, Chetty R. Traditional serrated adenoma: an overview of pathology and emphasis on molecular pathogenesis. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2019;6:e000317. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Sano W, Sano Y, Iwatate M, Hasuike N, Hattori S, Kosaka H, Ikumoto T, Kotaka M, Fujimori T. Prospective evaluation of the proportion of sessile serrated adenoma /polyps in endoscopically diagnosed colorectal polyps with hyperplastic features. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3:E354 –E358. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Hewett DG, Kaltenbach T, Sano Y, Tanaka S, Saunders BP, Ponchon T, Soetikno R, Rex DK. Validation of a simple classification system for endoscopic diagnosis of small colorectal polyps using narrow-band imaging. Gastroenterology. 2012;143: 599–607.e1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Hayashi N, Tanaka S, Hewett DG, Kaltenbach TR, Sano Y, Ponchon T, Saunders BP, Rex DK, Soetikno RM. Endoscopic prediction of deep submucosal invasive carcinoma: validation of the narrow-band imaging international colorectal endoscopic (NICE) classification. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:625 –632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Iwatate M, Sano Y, Tanaka S, Kudo SE, Saito S, Matsuda T, Wada Y, Fujii T, Ikematsu H, Uraoka T, Kobayashi N, Nakamura H, Hotta K, Horimatsu T, Sakamoto N, Fu KI, Tsuruta O, Kawano H, Kashida H, Takeuchi Y, Machida H, Kusaka T, Yoshida N, Hirata I, Terai T, Yamano HO, Nakajima T, Sakamoto T, Yamaguchi Y, Tamai N, Nakano N, Hayashi N, Oka S, Ishikawa H, Murakami Y, Yoshida S, Saito Y Japan NBI Expert Team (JNET) Validation study for development of the Japan NBI Expert Team classification of colorectal lesions. Dig Endosc. 2018;30:642–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Hazewinkel Y, de Wijkerslooth TR, Stoop EM, Bossuyt PM, Biermann K, van de Vijver MJ, Fockens P, van Leerdam ME, Kuipers EJ, Dekker E. Prevalence of serrated polyps and association with synchronous advanced neoplasia in screening colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 2014; 46: 219–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Carr NJ, Mahajan H, Tan KL, Hawkins NJ, Ward RL. Serrated and non-serrated polyps of the colorectum: their prevalence in an unselected case series and correlation of BRAF mutation analysis with the diagnosis of sessile serrated adenoma. J Clin Pathol. 2009; 62:516–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Abdeljawad K, Vemulapalli KC, Kahi CJ, Cummings OW, Snover DC, Rex DK. Sessile serrated polyp prevalence determined by a colonoscopist with a high lesion detection rate and an experienced pathologist. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:517–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Spring KJ, Zhao ZZ, Karamatic R, Walsh MD, Whitehall VL, Pike T, Simms LA, Young J, James M, Montgomery GW, Appleyard M, Hewett D, Togashi K, Jass JR, Leggett BA. High prevalence of sessile serrated adenomas with BRAF mutations: a prospective study of patients undergoing colonoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2006; 131: 1400–1407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Sano Y, Ikematsu H, Fu KI, Emura F, Katagiri A, Horimatsu T, Kaneko K, Soetikno R, Yoshida S. Meshed capillary vessels by use of narrow-band imaging for differential diagnosis of small colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009; 69:278– 283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Tadepalli US, Feihel D, Miller KM, Itzkowitz SH, Freedman JS, Kornacki S, Cohen LB, Bamji ND, Bodian CA, Aisenberg J. Morphologic analysis of sessile serrated polyps observed during routine colonoscopy (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2011; 74:1360–1368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Nakao Y, Saito S, Ohya T, Aihara H, Arihiro S, Kato T, Ikegami M, Tajiri H. Endoscopic features of colorectal serrated lesions using image-enhanced endoscopy with pathological analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013; 25:981–988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Hazewinkel Y, López-Cerón M, East JE, Rastogi A, Pellisé M, Nakajima T, van Eeden S, Tytgat KM, Fockens P, Dekker E. Endoscopic features of sessile serrated adenomas: validation by international experts using high-resolution white-light endoscopy and narrow-band imaging. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:916–924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Yamada M, Sakamoto T, Otake Y, Nakajima T, Kuchiba A, Taniguchi H, Sekine S, Kushima R, Ramberan H, Parra-Blanco A, Fujii T, Matsuda T, Saito Y. Investigating endoscopic features of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps by using narrow-band imaging with optical magnification. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82: 108– 117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Yamashina T, Takeuchi Y, Uedo N, Aoi K, Matsuura N, Nagai K, Matsui F, Ito T, Fujii M, Yamamoto S, Hanaoka N, Higashino K, Ishihara R, Tomita Y, Iishi H. Diagnostic features of sessile serrated adenoma/ polyps on magnifying narrow-band imaging: a prospective study of diagnostic accuracy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015; 30:117–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Kimura T, Yamamoto E, Yamano HO, Suzuki H, Kamimae S, Nojima M, Sawada T, Ashida M, Yoshikawa K, Takagi R, Kato R, Harada T, Suzuki R, Maruyama R, Kai M, Imai K, Shinomura Y, Sugai T, Toyota M. A novel pit pattern identifies the precursor of colorectal cancer derived from sessile serrated adenoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:460– 469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Sano W, Fujimori T, Ichikawa K, Sunakawa H, Utsumi T, Iwatate M, Hasuike N, Hattori S, Kosaka H, Sano Y. Clinical and endoscopic evaluations of sessile serrated adenoma/polyps with cytological dysplasia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;33: 1454–1460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Burgess NG, Pellise M, Nanda KS, Hourigan LF, Zanati SA, Brown GJ, Singh R, Williams SJ, Raftopoulos SC, Ormonde D, Moss A, Byth K, P’Ng H, McLeod D, Bourke MJ. Clinical and endoscopic predictors of cytological dysplasia or cancer in a prospective multicentre study of large sessile serrated adenomas/ polyps. Gut.2016;65:437–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Murakami T, Sakamoto N, Ritsuno H, Shibuya T, Osada T, Mitomi H, Yao T, Watanabe S. Distinct endoscopic characteristics of sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with and without dysplasia/carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:590–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Tanaka Y, Yamano HO, Yamamoto E, Matushita HO, Aoki H, Yoshikawa K, Takagi R, Harada E, Nakaoka M, Yoshida Y, Eizuka M, Sugai T, Suzuki H, Nakase H. Endoscopic and molecular characterization of colorectal sessile serrated adenoma /polyps with cytologic dysplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86:1131– 1138.e4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Tate DJ, Jayanna M, Awadie H, Desomer L, Lee R, Heitman SJ, Sidhu M, Goodrick K, Burgess NG, Mahajan H, McLeod D, Bourke MJ. A standardized imaging protocol for the endoscopic prediction of dysplasia within sessile serrated polyps (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:222–231.e2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Sano Y, Saito Y, Fu KI, Matsuda T, Uraoka T, Kobayashi N, Ito H, Machida H, Iwasaki J, Emura F, Hanafusa M, Yoshino T, Kato S, Fujii T. Efficacy of magnifying chromoendoscopy for the differential diagnosis of colorectal lesions. Dig Endosc. 2005;17: 105–116. [Google Scholar]

29. Yao T, Sugai T, Iwashita A, Fujimori T, Kushima R, Nokubi M, Mitomi H, Ajioka Y, Konishi F. Histopathological characteristics and diagnostic criteria of SSA/P, from project research “potential of cancerization of colorectal serrated lesions” of the Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum. Stomach Intestine. 2011; 46:442–448. [Google Scholar]

30. Fujimori Y, Fujimori T, Imura J, Sugai T, Yao T, Wada R, Ajioka Y, Ohkura Y. An assessment of the diagnostic criteria for sessile serrated adenoma/polyps: SSA/Ps using image processing software analysis for Ki67 immunohistochemistry. Diagn Pathol. 2012;7:59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Rex DK, Ahnen DJ, Baron JA, Batts KP, Burke CA, Burt RW, Goldblum JR, Guillem JG, Kahi CJ, Kalady MF, O’Brien MJ, Odze RD, Ogino S, Parry S, Snover DC, Torlakovic EE, Wise PE, Young J, Church J. Serrated lesions of the colorectum: review and recommendations from an expert panel. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012; 107:1315–29; quiz 1314, 1330. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Bettington M, Walker N, Clouston A, Brown I, Leggett B, Whitehall V. The serrated pathway to colorectal carcinoma: current concepts and challenges. Histopathology. 2013; 62:367–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Yang S, Farraye FA, Mack C, Posnik O, O’Brien MJ. BRAF and KRAS Mutations in hyperplastic polyps and serrated adenomas of the colorectum: relationship to histology and CpG island methylation status. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1452– 1459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. O’Brien MJ, Yang S, Mack C, Xu H, Huang CS, Mulcahy E, Amorosino M, Farraye FA. Comparison of microsatellite instability, CpG island methylation phenotype, BRAF and KRAS status in serrated polyps and traditional adenomas indicates separate pathways to distinct colorectal carcinoma endpoints. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30: 1491– 1501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Kim KM, Lee EJ, Ha S, Kang SY, Jang KT, Park CK, Kim JY, Kim YH, Chang DK, Odze RD. Molecular features of colorectal hyperplastic polyps and sessile serrated adenoma/polyps from Korea. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011; 35:1274 –1286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. O’Brien MJ, Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Gottlieb LS, Sternberg SS, Diaz B, Dickersin GR, Ewing S, Geller S, Kasimian D. The National Polyp Study. Patient and polyp characteristics associated with high-grade dysplasia in colorectal adenomas. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:371– 379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Gschwantler M, Kriwanek S, Langner E, Göritzer B, Schrutka-Kölbl C, Brownstone E, Feichtinger H, Weiss W. High-grade dysplasia and invasive carcinoma in colorectal adenomas: a multivariate analysis of the impact of adenoma and patient characteristics. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002; 14:183–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Sakamoto T, Matsuda T, Nakajima T, Saito Y. Clinicopathological features of colorectal polyps: evaluation of the ‘predict, resect and discard’ strategies. Colorectal Dis. 2013; 15:e295–e300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Hassan C, Quintero E, Dumonceau JM, Regula J, Brandão C, Chaussade S, Dekker E, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Ferlitsch M, Gimeno-García A, Hazewinkel Y, Jover R, Kalager M, Loberg M, Pox C, Rembacken B, Lieberman D European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Post-polypectomy colonoscopy surveillance: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2013; 45:842–851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Gupta S, Lieberman D, Anderson JC, Burke CA, Dominitz JA, Kaltenbach T, Robertson DJ, Shaukat A, Syngal S, Rex DK. Recommendations for Follow-Up After Colonoscopy and Polypectomy: A Consensus Update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91:463– 485.e5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Bettington M, Walker N, Rosty C, Brown I, Clouston A, McKeone D, Pearson SA, Leggett B, Whitehall V. Clinicopathological and molecular features of sessile serrated adenomas with dysplasia or carcinoma. Gut. 2017;66: 97–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Huang CS, O’brien MJ, Yang S, Farraye FA. Hyperplastic polyps, serrated adenomas, and the serrated polyp neoplasia pathway. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99: 2242 –2255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Kim KM, Lee EJ, Kim YH, Chang DK, Odze RD. KRAS mutations in traditional serrated adenomas from Korea herald an aggressive phenotype. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:667–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar

Credits: Sano W, Hirata D, Teramoto A, et al. Serrated polyps of the colon and rectum: Remove or not?. World J Gastroenterol. 2020; 26(19):2276-2285. doi:10.3748/wjg. v26. i19.2276