Masket, Samuel MD

From Advanced Vision Care, Los Angeles, California; and Stein Eye Institute, Los Angeles, California.

Corresponding author: Samuel Masket, MD, Suite 911, 2080 Century Park East, Los Angeles, CA 90067. Email: avcmasket@aol.com.

ABSTRACT

Cyclodialysis clefts are often associated with ocular hypotony and attendant maculopathy. However, these clefts create an alternative aqueous outflow pathway that can be useful to maintain intraocular pressure (IOP) at physiologic levels under some conditions. At normal levels of IOP, they might prevent glaucoma damage and avoid maculopathy of hypotony. Indeed, historically, cyclodialysis was a planned surgical method for managing glaucoma, and more recently, a minimally invasive glaucoma surgery device that created a small-stented cyclodialysis was in use until removed from the market for unrelated concerns. Cataract surgery in the presence of a cleft, however, might be complicated by extensive fluid misdirection through the cleft with resultant large suprachoroidal effusion. A technique of ab interno temporary suture cyclohexyl was devised for a patient needing cataract surgery with an existing traumatic cyclodialysis cleft that was vital for long-term management of IOP. The suture was used to close the cleft transiently during surgery and was removed at the close of the procedure to reestablish patency and preserve the cleft.

An ab interno suture cyclohexyl technique was developed to maintain the long-term patency of a cyclodialysis cleft while temporarily closing it during cataract surgery to prevent massive suprachoroidal effusion.

Inadvertent traumatic or iatrogenic cyclodialysis is often associated with ocular hypotony and associated maculopathy.1 As a result, a number of techniques have been described to close undesired cyclodialysis clefts.2 However, in an era prior to trabeculectomy and long before minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS), cyclodialysis was a variably successful glaucoma surgery that could also be combined with (intracapsular) cataract extraction.3–5 Indeed, the supraciliary space is the target for the CyPass MIGS (Alcon Laboratories, Inc.) device.6 However, that product was subsequently removed from the market because the stent was responsible for endothelial cell loss. Historically, functional cyclodialysis clefts could maintain intraocular pressure (IOP) at satisfactory levels but might close abruptly with a resultant sudden elevation of IOP; chronic miotic therapy was often used in an attempt to retain patency of the cleft by maintaining stimulation and tension on the circumferential ciliary muscle. As more consistently successful techniques evolved, cyclodialysis fell into disuse as a surgical strategy for uncontrolled glaucoma. That said, an inadvertent cyclodialysis cleft might and can be useful in maintaining IOP control. Given a patient with a traumatic cataract and a concomitant cleft that achieves IOP control, it would be useful to preserve the cleft’s function after cataract surgery. However, one concern about performing cataract surgery in the presence of a functional cleft is possible fluid misdirection through the cleft and the potential for a massive suprachoroidal effusion (Figure 1). The challenge, then, is to close the cyclodialysis transiently during surgery to prevent fluid misdirection yet allow the cleft to reopen at the close of surgery to provide for long-term IOP control. The following case example is illustrative of the condition and the technique for management:

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

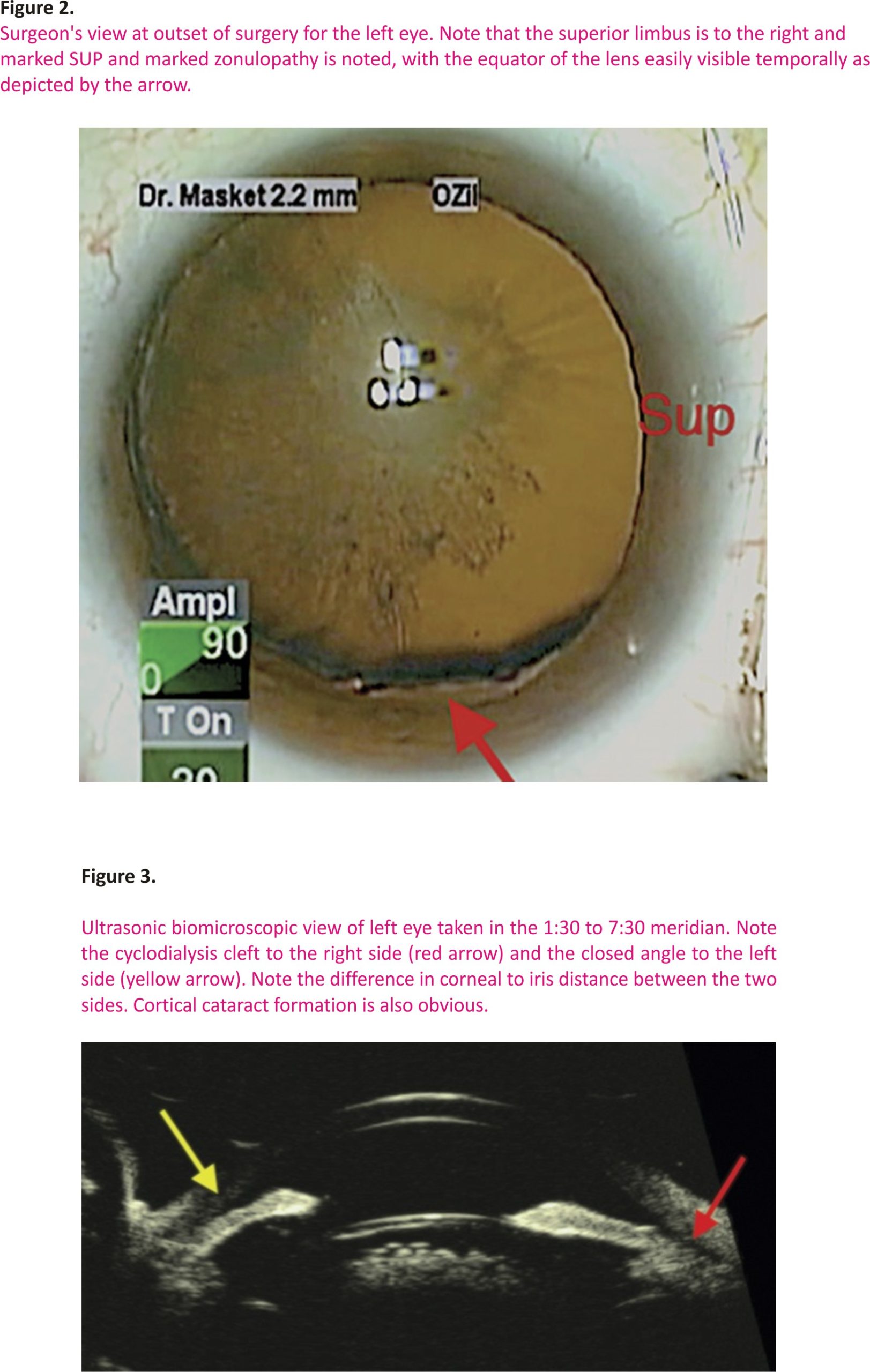

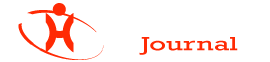

In 2011, a then 55-year-old woman sustained a bungee cord injury to her left eye and was referred for cataract management 2 years later. According to the initial treating and referring ophthalmologist, after clearing of hyphema, her course was unremarkable, and IOP was always in the low normal to normal range. At evaluation in 2013, she was noted to have an advanced cortical and posterior subcapsular cataract, several clock hours of zonulopathy temporally and inferiorly, anterior chamber vitreous prolapse, minor pupil sphincter tears, and a normal posterior segment (Figure 2). Corrected distance visual acuity was 20/20 in the right eye (RE) and 20/200 in the left eye (LE), and IOP was 14 mm Hg and 11 mm Hg for the RE and LE, respectively. Serial IOP measurements for the LE ranged between 8 and 15 mm Hg. Gonioscopy for the uninvolved RE revealed a wide-open unremarkable angle for 360 degrees. However, for the LE, the angle appeared to be scarred closed for all but 1 to 1.5 clock hours inferonasal, where, in the 7:30 meridian, a cyclodialysis was noted and confirmed by ultrasound biomicroscopy (Figure 3).

Given an advanced and symptomatic cataract, she requested surgery. Because there was marked zonulopathy and vitreous prolapse, surgery would likely be prolonged. With a patent cyclodialysis cleft and the likelihood for lengthy surgery with resultant increased balanced salt solution infusion, there was a logical concern for suprachoroidal effusion and possible haemorrhage. Although the cleft could have been closed surgically prior to cataract removal in a separate procedure, it would likely have resulted in intractable glaucoma because the remainder of the angle was scarred closed, and the cleft had likely successfully maintained IOP in the normal range since the injury 2 years earlier. Therefore, it seemed prudent to devise a technique to close the cyclodialysis cleft at the outset of surgery and reverse it at the end of the procedure with the hope that the cleft would retain long-term function.

An ab interno suture cyclohexyl was planned: at the surgery in 2013, after bimanual triamcinolone–assisted removal of prolapsed vitreous, the anterior chamber was deepened with cohesive ophthalmic viscosurgical device to maintain chamber depth, and a horizontal mattress suture cyclohexyl was performed in the inferonasal quadrant, centring at the 7:30 meridian, corresponding to the cyclodialysis cleft and following episcleral vessels that were previously identified as being superficial to the cleft. As can be noted in the video, a double-armed 10-0 polypropylene suture on a long-curved needle (CIF-4, Alcon Laboratories, Inc.) was passed through a superior paracentesis across the anterior chamber with care taken to avoid damaging the anterior lens capsule (Video 1, available at http://links. lww. com/JRS/A282). The needle was directed underneath the iris into the ciliary sulcus, pierced the ciliary body, and exited the sclera and conjunctiva about 2.0 mm posterior to the limbus. The second arm of the suture was passed through the same paracentesis and exited the sclera about 3.0 mm apart from the first arm of the suture, creating a single horizontal mattress suture that was tied externally, closing the cyclodialysis cleft. Complex but uneventful cataract surgery then ensued with the use of capsule support hooks (MST), a capsule tension ring (Morcher), and one Ahmed Capsule Tension Segment (Morcher) sewn to the sclera inferotemporally; a single-piece acrylic intraocular lens was placed in the capsule bag. Pars plana removal of vitreous was necessary because additional vitreous prolapsed around the large area of zonulysis during surgery. Once anterior chamber procedures were completed, the cyclohexyl mattress suture was removed, and a miotic was instilled to reopen the cleft.

The postoperative course was unremarkable with corrected distance visual acuity of 20/20, and the patient has been maintained on pilocarpine HCL 1% once daily in an attempt to keep the cleft open and functional. Now, 7 years postoperatively, IOP remains physiologic, averaging 10 mm Hg, and the cleft remains open.

DISCUSSION

The uveoscleral pathway for aqueous egress has achieved popularity with regard to pharmacologic and surgical management of elevated IOP. Although cyclodialysis was at one time a viable but variably successful surgical strategy, it often failed due to undesired and sudden closure of the cleft with rapid and marked elevation of IOP. It is interesting to note, however, that the 1 MIGS model, CyPass, was designed to create a permanent, albeit stented, cyclodialysis. As noted earlier, however, the device has been removed from the market owing to the loss of endothelial cells from stent abrasion.7 Nonetheless, the uveoscleral aqueous outflow pathway remains a potentially valuable strategy for IOP control. The procedure described in this study affords surgeons the opportunity to safely perform cataract surgery in the presence of a cyclodialysis cleft and to maintain its function postoperatively. As experience with the case at hand reveals, IOP has remained within the normal range 9 years post-injury and 7 years post-cataract surgery, despite extensive scarring of the filtering angle. Although ab interno permanent cyclohexyl has been well-described, to our knowledge, the transient closure technique described in this study is unique.8

WHAT WAS KNOWN

Cyclodialysis clefts induce ocular hypotony and maculopathy.

A variety of methods exist for permanent cyclodialysis closure.

Cyclodialysis with uveoscleral aqueous outflow is one surgical method for managing glaucoma.

WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS

- Extensive suprachoroidal effusion might occur during cataract surgery in the presence of a cyclodialysis cleft.

- Temporary internal suture cyclohexyl might be used to preserve a functional cyclodialysis and prevent intraoperative massive suprachoroidal effusion.

REFERENCES

1. Ioannidis AS, Barton K. Cyclodialysis cleft: causes and repair. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2010;21:150–154

2. Gonzalez-Martín-Moro J, Contreras-Martín I, Munoz-Negrete FJ, Gome Sanz F, Zarallo-Gallardo J. Cyclodialysis: an update. Int Ophthalmol 2017; 37:441–457

3. Razeghinejad MR, Spaeth GL. A history of the surgical management of glaucoma. Optom Vis Sci 2011; 88:E39–E47

4. Bellows AR, Johnstone MA. Surgical management of chronic glaucoma in aphakia. Ophthalmology 1983; 90:807–813.

5. Gross RL, Feldman RM, Spaeth GL, Steinmann WC, Spiegel D, Katz LJ, Wilson RP, Varma R, Moster MR, Marks S. Surgical therapy of chronic glaucoma in aphakia and pseudophakia. Ophthalmology 1988;95:1195–1201.

6. Richter GM, Coleman AL. Minimally invasive glaucoma surgery: current status and future prospects. Clin Ophthalmol 2016;10:189–206

7. Garcia-Feijoo J. CyPass stent with- drawal: the end of suprachoroidal MIGS?. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol 2019;94:1–3

8. Selvan H, Gupta V, Gupta S. Cyclodialysis: an updated approach to surgical strategies. Acta Ophthalmol 2019;97:744–751

Credits: Masket, Samuel MD Temporary ab interno suture cyclohexyl for closing a cyclodialysis cleft during cataract surgery, Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery: October 2021 – Volume 47 – Issue 10 – p 1369-1371

doi: 10.1097/j.jcrs.0000000000000528