Kelcee A. Everette, Gregory A. Newby, Rachel M. Levine, Kalin Mayberry, Yoonjeong Jang, Thiyagaraj Mayuranathan, Nikitha Nimmagadda, Erin Dempsey, Yichao Li, Senthil Velan Bhoopalan, Xiong Liu, Jessie R. Davis, Andrew T. Nelson, Peter J. Chen, Alexander A. Sousa, Yong Cheng, John F. Tisdale, Mitchell J. Weiss, Jonathan S. Yen & David R. Liu

Abstract

Sickle-cell disease (SCD) is caused by an A·T-to-T·A transversion mutation in the β-globin gene (HBB). Here we show that prime editing can correct the SCD allele (HBBS) to wild type (HBBA) at frequencies of 15%–41% in haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) from patients with SCD. Seventeen weeks after transplantation into immunodeficient mice, prime-edited SCD HSPCs maintained HBBA levels and displayed engraftment frequencies, haematopoietic differentiation, and lineage maturation similar to those of unedited HSPCs from healthy donors. An average of 42% of human erythroblasts and reticulocytes isolated 17 weeks after transplantation of prime-edited HSPCs from four SCD patient donors expressed HBBA, exceeding the levels predicted for therapeutic benefit. HSPC-derived erythrocytes carried less sickle haemoglobin, contained HBBA-derived adult haemoglobin at 28%–43% of normal levels, and resisted hypoxia-induced sickling. Minimal off-target editing was detected at over 100 sites nominated experimentally via unbiased genome-wide analysis. Our findings support the feasibility of a one-time prime editing SCD treatment that corrects HBBS to HBBA, does not require any viral or non-viral DNA template, and minimizes undesired consequences of DNA double-strand breaks.

Main

Sickle-cell disease (SCD) is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by an A·T-to-T·A mutation in the haemoglobin subunit beta (HBB) gene, resulting in the pathogenic sickle-cell allele (HBBS) encoding a Glu 6→Val (E6V) substitution. This mutation changes normal adult β-globin (βA) to sickle β-globin (βS) and replacement of normal adult haemoglobin (HbA, α2β2) with sickle haemoglobin (HbS, α2βS2). At low oxygen tension, HbS forms rigid polymers that cause characteristic red blood cell (RBC) shape changes and initiate a complex pathophysiology that includes haemolysis, microvascular occlusions, and inflammation. Clinical manifestations include anaemia, immunodeficiency, multi-organ damage, severe acute and chronic pain, and premature death1.

The only FDA-approved cure for SCD is allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. However, most patients lack ideal donors and the procedure is associated with serious toxicities, including graft-vs-host disease and graft rejection2. Correction of the patient’s own hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) bypasses immune complications and eliminates the need for a tissue-compatible donor. Current strategies for therapeutic manipulation of SCD hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) being examined in clinical trials include lentiviral expression of an anti-sickling β-like globin3 and the use of genome editing nucleases or base editors to activate γ-globin gene transcription for induction of foetal haemoglobin (HbF, α2γ2)4,5,6,7,8,9. A clinical trial using Cas9 nuclease-initiated homology-directed repair (HDR) and an adeno-associated virus type 6 (AAV6)-delivered DNA template to correct the SCD mutation10 was stopped due to a patient developing transfusion-dependent pancytopenia11. Another HDR-based strategy that uses non-viral delivery of a single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide donor12 has been approved for a clinical trial. We recently reported a base editing strategy using an adenine base editor to convert the pathogenic HBBS allele into the non-pathogenic, naturally occurring Makassar allele (HBBG)13. While each of these strategies has distinct advantages and disadvantages, reverting the SCD E6V substitution, which requires a T·A-to-A·T transversion, represents the most physiological approach for disease correction. However, base editors cannot convert T·A to A·T, and nuclease-mediated HbF induction or HDR-mediated correction of HBB requires double-stranded DNA breaks (DSBs) that cause uncontrolled mixtures of on-target loss-of-function insertion and deletion (indel) mutations 12,14, p53 activation and chromosomal abnormalities15,16,17,18,19,20,21. Moreover, strategies that require co-delivery of the HDR template by AAV transduction 10,22 have the potential to impair HSC engraftment14,23, which can result in transfusion-dependent pancytopenia11.

An ideal treatment for SCD would permanently revert HBBS to the wild-type allele (HBBA) with few deleterious genomic alterations or cell state changes. Because prime editing replaces a target segment of DNA with a specified new sequence up to hundreds of base pairs in length, it enables the installation of targeted insertions, deletions, and any base-to-base substitutions directly into the genome of living cells and animals without requiring DSBs24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. Here we report the development of a prime editing strategy that reverts the SCD allele back to wild-type HBBA with high on-target efficiency, low frequencies of indel by-products, and minimal off-target editing. Edited SCD patient HSPCs maintained prime editing levels at 17 weeks after transplantation in mice, with an average of 42% of engrafted human erythroblasts and reticulocytes across four patient donors containing at least one wild-type HBBA allele, indicating robust editing of hematopoietic stem cells at levels that exceed the estimated therapeutic threshold. Treated cells also showed a significant reduction in sickling when cultured in hypoxic conditions. Minimal off-target editing was detected following the analysis of over 100 experimentally identified CIRCLE-seq-nominated candidate off-target sites engaged by the prime editing system, suggesting a high degree of target DNA specificity. Taken together, our results establish an early example of therapeutic prime editing in human HSCs and demonstrate a potential strategy for a one-time autologous SCD treatment that directly corrects the sickle globin allele back to wild-type HBB without requiring DSBs or donor DNA templates.

Results

Optimizing prime editing systems for HSPCs

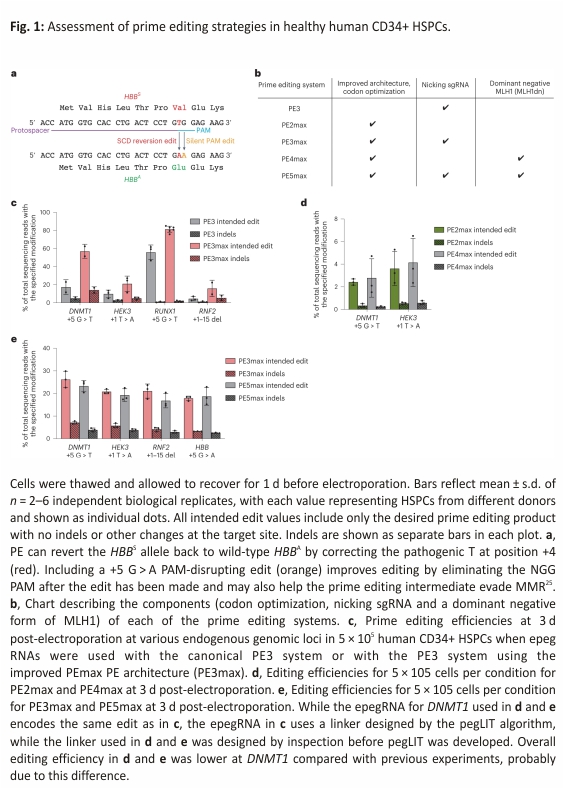

We previously reported the use of prime editing to correct HBBS by plasmid transfection in HEK293T cells containing the SCD mutation, reaching up to 58% efficiency (Fig. 1a)24. In contrast to HEK293T cells, HSPCs are difficult to transfect with plasmid DNA but are amenable to RNA electroporation, an ex vivo delivery method that has been used in the clinic to manipulate HSPCs before transplantation6,7,32. We sought to identify an RNA electroporation-based prime editing strategy for HSPCs that incorporates recent prime editing advances (Figs. 1 and 2). We recently designed improved engineered pegRNAs (epegRNAs)26 that incorporates a 3′ structured motif to protect the reverse transcriptase template (RTT) from exonuclease degradation and an 8 nt linker that hinders potential interference between the motif and the RTT (Extended Data Fig. 1a). The linker can be designed optimally with an algorithm (pegLIT) or less effectively by visual inspection26. In addition, we developed PEmax, an improved prime editor (PE) architecture with optimized Cas9 and nuclear localization sequences, and codon usage25 (Fig. 1b). We compared editing outcomes following the electroporation of in vitro-transcribed PE and PEmax messenger RNA (mRNA) with synthetic epegRNAs in healthy human donor HSPCs to install various edits across four genomic loci—DNMT1 (both with a fully optimized linker as in Fig. 1c and with a linker chosen by inspection as in Fig. 1d,e), HEK293T genomic site 3 (hereafter referred to as HEK3), RUNX1 and RNF2 (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Both PE and PEmax mRNA together with epegRNAs and nicking single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) supported substantial prime editing efficiencies in HSPCs (up to 85%), with PEmax conferring 1.3- to 3.5-fold average increases in editing efficiency over PE (Fig. 1c). Thus, PEmax mRNA can be electroporated together with synthetic epegRNAs and nicking sgRNAs to robustly edit primary human HSPCs.

In addition to the improved PEmax architecture, our group previously reported that prime editing outcomes can be improved by inhibiting mismatch repair (MMR) using transient co-expression of MMR protein MLH1 (MLH1dn), a dominant negative MLH1 variant25, or by installing benign or silent mutations near the desired edit that cause the prime editing intermediate to naturally evade MMR. PE4 and PE5 systems transiently co-express MLH1dn with PE2 and PE3, respectively25 (Fig. 1b). Impeding MMR increases prime editing efficiencies for small substitutions, insertions, and deletions and decreases the formation of indel by-products in a wide variety of cells25,33. To determine whether PE4max or PE5max might increase desired editing outcomes over PE2max and PE3max in primary human HSPCs, we electroporated in vitro-transcribed RNA encoding all prime editing components and MLH1dn into healthy donor cells. Surprisingly, transient MLH1 expression did not improve prime editing over PE2max or PE3max in HSPCs (Fig. 1d,e). The +5 G > T edit at DNMT1 and the +5 G > A edit at HBB are silent protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) alterations that may help the prime editing intermediate natively evade MMR, without MLH1dn. However, the intermediate mismatch to install the +1 HEK3 T > A is a known substrate for MMR25, and the prime editing efficiency in HSPCs of +1 HEK3 T > A also does not benefit from the addition of MLH1dn. Similarly, editing efficiencies for the +1–15 deletion at RNF2 in primary human HSPCs also did not benefit from the addition of MLH1dn (Fig. 1d,e).

We also compared prime editing at HBB with PE3 versus PE5 (not ‘max’ architecture) using a pegRNA or an epegRNA in healthy human HSPCs under conditions in which prime editing was limiting and thus the benefits of MMR evasion would be most easily manifested. We observed no improvement in prime editing from MLH1dn expression (Extended Data Fig. 1b). Consistent with these results, we also pretreated primary human HSPCs with small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting MLH1 and observed no benefit to PE3 prime editing outcomes at HBB compared with the identical treatment using non-targeting siRNAs (Extended Data Fig. 1b). These observations collectively suggest that cellular MMR may not limit the efficiency of this prime edit in HSPCs under these conditions. A recent study reports that constitutive expression of MLH1dn in a PE5max strategy shows increased editing efficiency compared with PE3max in human HSPCs edited with helper-dependent adenovirus vector34. Since expression from mRNA is much more transient than viral expression, we speculate that the timing of MLH1dn following mRNA electroporation in HSPCs may be less effective at enhancing prime editing outcomes than longer-lasting MLH1dn expression, or that the combination of the target edit and the adjacent silent PAM edit is sufficient to cause the prime editing intermediate to evade MMR. We, therefore, continued optimizations using electroporation-based prime editing systems with epegRNAs and PE3max and without MLH1dn.

Optimizing prime editing agents to revert HBBS to HBBA

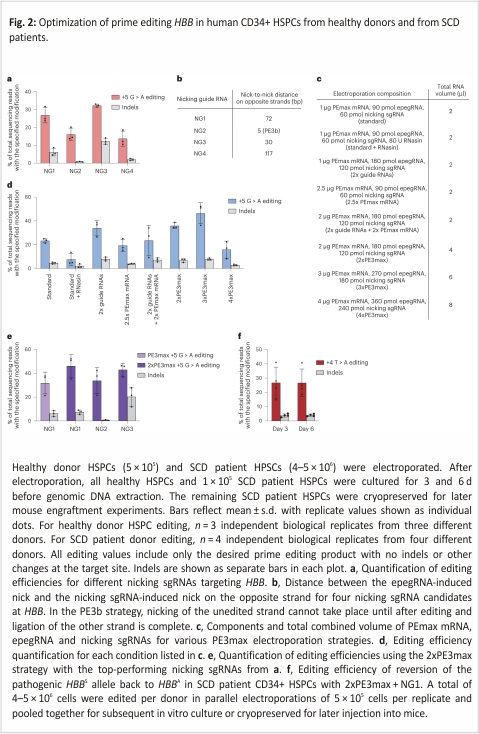

We sought to further optimize editing outcomes at the HBBS locus in primary human CD34+ cells. We designed an epegRNA that would both revert the pathogenic sickle mutation and allow optimization in healthy (homozygous HBBA) donor CD34+ cells by including a silent PAM edit (Extended Data Fig. 1c). We first removed the 5′ G required for efficient guide expression from plasmids and included an 8 nt linker designed by pegLIT, a computational tool that identifies non-interfering nucleotide linkers between pegRNAs and 3′ epegRNA motifs26. Additionally, we appended a UUU trinucleotide to the 3′ ends of the epegRNA for additional protection from degradation, with each uracil harboring a 2′-O-methyl modification and with three phosphorothioate linkages, one before each 3′ uracil nucleotide26. On average, epegRNAs containing this modified trinucleotide conferred a 1.4-fold increase in prime editing efficiency with a similar product purity compared to epegRNAs lacking the 3′ modified UUU (Extended Data Fig. 1d). We also included a silent PAM-disrupting edit in the epegRNA (+5 G > A), which prevents the re-engagement of target DNA after prime editing and serves as a marker to assess prime editing efficiencies in healthy donor CD34+ cells that lack the pathogenic +4 T > A HBBS mutation.

We electroporated the newly designed synthetic epegRNA together with in vitro-transcribed PEmax mRNA and synthetic nicking sgRNA NG1 (constituting a PE3max system) into healthy human donor HSPCs (Fig. 2a). We collected genomic DNA from treated cells (without enriching for transfected cells) at 3 d following electroporation and assessed on-target editing by high-throughput sequencing (HTS). We observed the desired precise prime editing outcome without any indels or other unwanted target site changes at an average efficiency of 27% (Fig. 2a). This observation demonstrated that synthetic epegRNAs containing a modified 3′ UUU trinucleotide support substantial prime editing efficiencies in primary human CD34+ cells.

To further optimize the PE3max system, we screened multiple HBB-nicking sgRNAs (NGs, Fig. 2a,b). We tested three additional NGs, including a PE3b nicking sgRNA that cannot nick the unedited strand until after the desired prime edit has occurred on the opposite strand. We previously established that PE3b editing strategies minimize indel by-products from prime editing by reducing the frequency of intermediates containing simultaneous nicks in both DNA strands24. Indel formation at this target site can eliminate HBB expression or create non-functional mutant proteins. Indeed, the PE3b nicking sgRNA (NG2) yielded the best ratio of desired edit to indel by-products, with 16 ± 3.5% desired editing and only 0.75 ± 0.16% indels at 3 d post-electroporation (Fig. 2a). However, desired on-target editing using NG2 was lower than our original nicking sgRNA (NG1), which resulted in 27 ± 4.3% desired editing and 6.2 ± 2.2% indels. While NG3 resulted in higher on-target editing (32 ± 0.81%), this increased editing efficiency was accompanied by higher levels of indels (12 ± 1.8%). NG4 achieved only 14 ± 4.3% editing with 2.0 ± 0.58% indels. Together, these results establish that the choice of the nicking sgRNA substantially impacts HBBS prime editing outcomes.

Optimizing ratios and volumes of electroporation editing reagents

Next, we identified efficiency bottlenecks in ex vivo prime editing of HSPCs and determined the optimal ratio of PEmax mRNA to synthetic epegRNA and nicking sgRNA. Keeping the guide RNAs and PEmax mRNA at 10% of the total electroporation volume following the Lonza 4D manufacturer’s recommendation, we doubled the concentration of guide RNAs, PEmax mRNA, or both (Fig. 2c). Additionally, we doubled, tripled, or quadrupled the total volume of all RNAs added per electroporation beyond the manufacturer’s suggestion. Finally, we tested the addition of RNasin, which has been previously reported to increase the efficiency of RNA-based electroporations by inhibiting endogenous RNase activity35 (Fig. 2c).

Among these variables, we found that increasing the total volume of editing reagents, but not changing the ratio of PEmax mRNA: guide RNAs, or adding RNasin, had the largest effect on prime editing outcomes. The standard volumes of PEmax mRNA and guide RNAs resulted in 23% desired editing without other target site changes. However, increasing the volume of the delivered RNAs to 2-fold higher than the amount recommended by Lonza increased on-target editing to 36% (Fig. 2d). A 3-fold increase of RNA editing reagents over the recommended volumes further increased on-target editing to 46%. However, cell viability decreased from 87% to 70% (Extended Data Fig. 1e). A 4-fold increase over the suggested volume of RNAs substantially reduced editing efficiency to 16% and greatly reduced cell viability to 17%. All other conditions tested failed to outperform the 2-fold increase of delivered RNAs. Our findings show that editing efficiency can be enhanced by optimizing the ratio between the in vitro-transcribed PEmax mRNA and the synthetic guide RNAs and that increasing the volume of editor reagents above 20% of the total volume of electroporation harms cell viability. In light of these results, we used 20% by volume PEmax mRNA and guide RNAs for all subsequent electroporation experiments.

To determine whether 20% by volume of PE3max could improve editing with different nicking guides (Ng1–3), we tested and compared each nicking sgRNA (Fig. 2e). We observed increased desired editing from using the original nicking sgRNA, NG1 (46 ± 9.5% desired editing with no other target site changes), with modest indel frequency (7.4 ± 1.8%); increased editing for NG2, the PE3b nicking sgRNA (34 ± 11%) with minimal indels (0.61 ± 0.36%); and increased editing for NG3 (43 ± 5.3%) with high indel levels (20 ± 8%). Together, these results indicate that the improvement in editing efficiency from using a 2x volume of reagents in the electroporation reaction is applicable across multiple nicking sites. Since the frequency of indel-free on-target editing (46%) was highest for NG1, we used this nicking sgRNA, the epegRNA optimized above and in vitro-transcribed PEmax mRNA as our strategy to directly revert the HBBS allele in HSPCs from SCD patients.

HBBS correction in SCD patient HSPCs

For prime editing of patient HSPCs, we thawed cryopreserved Plerixafor-mobilized CD34+ cells from three SCD patient donors, or CD34+ cells isolated from cryopreserved bone marrow from two additional SCD patient donors and then allowed them to recover for 1 d (Supplementary Table 3). Next, we electroporated the patient cells and healthy donor HSPCs in parallel using the optimized PE3max system. We maintained 100,000 cells in culture to extract genomic DNA at days 3 and 6 and cryopreserved the remaining cells for mouse engraftment experiments. Edited CD34+ cells from four different SCD patient donors showed an average of 26 ± 10% desired prime editing of HBBS to wild-type HBBA by day 3 and 27 ± 10% editing by day 6 (Fig. 2f). Compared with these samples, CD34+ HSPCs from a fifth SCD patient exhibited poor editing with extensive cell aggregation at day 3 and were not carried forward into subsequent experiments.

Indel frequencies in prime-edited HSPCs remained low, averaging 3.9 ± 1.2% and 4.6 ± 1.8% on days 3 and 6 respectively, reinforcing that prime editing leads to much fewer indels and much higher desired edit-to-indel ratios (5.9–6.7) than current HBBS correction strategies that utilize Cas9 nuclease-HDR, which have reported indel frequencies of 28–45% and edit-to-indel ratios of 0.74–1.612,14,24. The most efficiently edited patient HSPCs exhibited 41% HBBS-to-HBBA correction, with 5.2% indels at day 3, representing an edit-to-indel ratio of 7.9. While the frequency of specific indel outcomes varied by the donor, no single indel outcome represented more than 0.02% of total sequencing reads for any donor sample (Supplementary Tables 4–7). Editing efficiency for the silent PAM-disrupting +5 G > A edit was nearly identical to that of the +4 T > A reversion edit for all SCD patient donors, consistent with the processive mechanism of prime editing24 (Extended Data Fig. 1f). Thus, our optimized prime editing system robustly reverts the HBBS allele back to wild-type HBBA in SCD patient HSPCs with high reversion to indel ratios.

Transplantation of prime-edited human HSPCs into mice

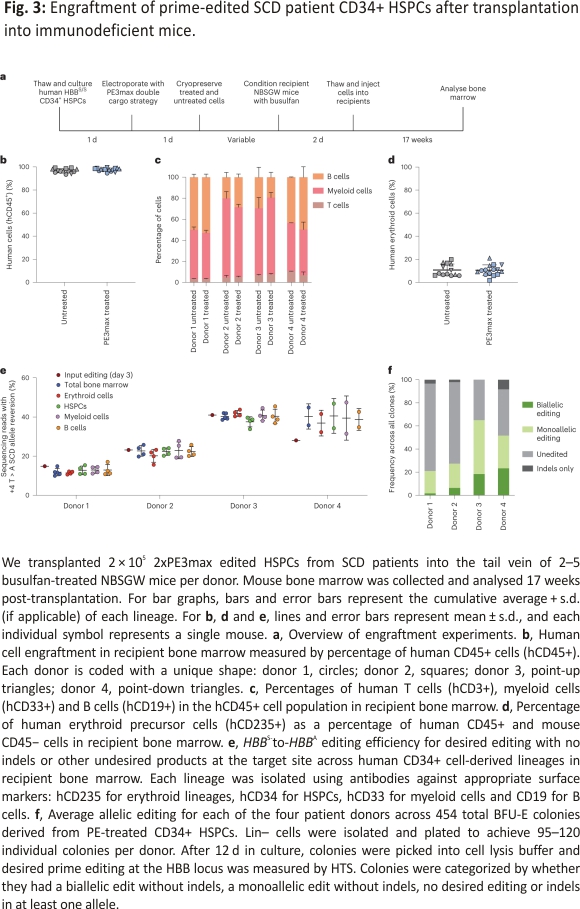

To determine whether prime-edited HSPCs from SCD donors can repopulate bone marrow in vivo, we thawed cryopreserved prime-edited and untreated HSPCs from four SCD donors, then transplanted each via tail-vein injection into 2–5 immunodeficient NOD B6.SCID Il2rγ−/−KitW41/W41 (NBSGW) mice, which were pretreated with low-dose busulfan at 2 d before injection to enhance donor HSPC engraftment36 (Fig. 3a). We collected the bone marrow of the mice for analysis 17 weeks post-injection, a time when most or all remaining human cells have been demonstrated to be derived from bone-marrow-repopulating HSCs37.

The engraftment, expansion, and differentiation of human HSCs can be altered by genome editing 38,39. To investigate whether these parameters were affected by prime editing of HBBS, we used flow cytometry with human-specific antibodies to quantify human donor cells in recipient mouse bone marrow. Human cells expressing the CD45 hematopoietic antigen represented approximately 97% of all bone marrow cells in recipient mice (Fig. 3b), in which the prime-edited cells engrafted with efficiencies comparable to untreated cells, indicating that there was no engraftment impairment, in contrast with nuclease-initiated HDR methods14. The frequencies of human B cells (CD19+), myeloid cells (CD33+), T cells (CD3+), and erythroid cells (CD235a+) were similar in bone marrow reconstituted with prime-edited HSPCs and untreated control HSPCs (Fig. 3c,d and Supplementary Table 8). We next used lineage-specific antibodies to purify SCD patient donor mononuclear cells (CD45+, ‘total bone marrow’), erythroblasts (CD235a+), HSPCs (CD34+), myeloid cells (CD33+) and B cells (CD19+) (Supplementary Table 8 and Extended Data Fig. 2a) and quantified the frequency of HBBS reversion across all lineages for each of the four donors. The prime editing frequencies of the injected cell population (15 to 41%) largely matched the levels of editing across all lineages (12 ± 0.62 to 40 ± 1.6%) recovered at 17 weeks post-transplantation (Fig. 3e). Together, these findings indicate that prime editing is retained at high frequency in bone-marrow-repopulating HSCs, which remains a challenge for some editing strategies that require DSBs14. Moreover, prime editing did not appear to alter HSC differentiation or maintenance of the lineages examined after bone marrow transplantation.

Of note, one donor achieved higher editing levels in all human cell populations collected from mouse bone marrow compared with input editing levels at day 3 (donor 4, Fig. 3e). This engrafted donor was the only one in which HSPCs were isolated from cryopreserved bone marrow, while all HSPC populations for all other engrafted donors were collected from Plerixafor-mobilized blood. It is tempting to speculate that the propensity of HSCs for prime editing may vary according to the HSPC source. Although the editing frequencies of repopulating cells were higher than that of input cells for this donor, all donor-derived lineages present in recipient bone marrow exhibited similar editing frequencies (Fig. 3e), consistent with our findings that PE-mediated conversion of HBBS to HBBA in bone-marrow-repopulating HSCs can be as efficient as that in the bulk HSPC population and that prime editing does not impact HSC lineage outcomes.

Next, we determined clonal editing outcomes among engrafted cells in mice at 17 weeks post-transplantation. We isolated human HSPCs (Cd34+) and CD235a+ cells from the bone marrow of PE3max-treated or untreated mice via magnetic-activated cell sorting and seeded them into semi-solid methylcellulose medium to generate clonal burst-forming unit-erythroid (BFU-E) colonies. We isolated 454 colonies distributed approximately equally from mice transplanted with four different HSPC donors. From the different donors, we observed 21–65% of clones harbouring the precise reversion edit in one (19–47%) or both (2–23%) HBBS alleles without any target site indels, while 35–76% were unedited (Fig. 3f). The remaining 0–8% of clones had indels in at least one allele, with 44% of those colonies also containing an intact allele with the desired edit (Extended Data Fig. 2b). These clonal editing outcomes reveal that PE3max-treated cells can be corrected at a level that substantially exceeds the 20% of corrected cells thought to be therapeutic in SCD patients40,41. Overall, our results demonstrate that prime-edited cells support hematopoietic repopulation and sustain predicted therapeutic levels of editing in long-term HSC populations.

Prime editing corrects SCD characteristics in RBCs from transplanted human HSCs

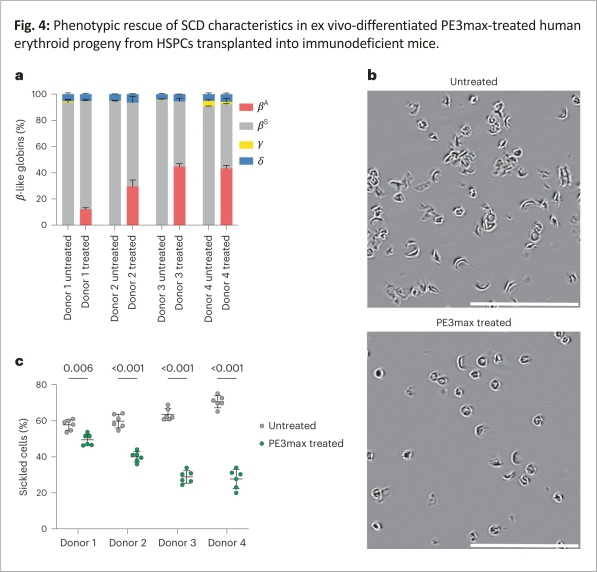

To determine the phenotypic impact of prime editing-mediated reversion of the sickle-cell mutation, we isolated CD235a+ cells from the bone marrow of transplanted mice and quantified the relative fractions of β-like globin proteins by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). We observed a decrease in HbS and an increase in HbA that were proportional to the frequency of editing observed in the total bone marrow and other lineages (Fig. 4a). Three of the four donors were edited with over 20% efficiency, with 30–45% HbA in bone-marrow-derived CD235a+ cells. We observed a similar result in SCD patient HSPCs differentiated toward erythroid cells in vitro (Extended Data Fig. 3a,b), with HbA production ranging from 28 to 43% (Extended Data Fig. 3c). On average, the maturation stages of erythroid precursors, including anucleate reticulocytes, were similar between in vitro-differentiated prime-edited SCD HSPCs and unedited healthy donor HSPCs (Extended Data Fig. 3d,e). These results reveal that direct reversion of HBBS with the optimized prime editing strategy rescued HbA production, proportionately reduced pathogenic HbS levels, and did not alter erythroid maturation.

The hallmark phenotype of SCD is the sickling of RBCs under hypoxic conditions. To determine whether prime editing of SCD patient HSPCs to revert HBBS to wild-type HBBA reduces sickling in hypoxic conditions, we incubated purified reticulocytes from mice 17 weeks after transplantation and incubated them in 2% O2. All reticulocytes from mice receiving prime-edited cells showed a substantial reduction in sickling from an average of 63% sickled cells in untreated controls to 37% sickled cells in cells derived from prime-edited mice (Fig. 4b,c). The reduction of sickling was approximately proportional to the level of HbA in edited cells. These data together establish that prime editing can durably modify repopulating human HSCs, resulting in the production of HbA-expressing reticulocytes that resist hypoxia-induced sickling.

Genome-wide off-target editing analysis

Studies from multiple groups have reported that prime editing causes substantially lower levels of off-target editing compared with other CRISPR gene editing methods, consistent with the mechanism of prime editing, which requires three separate base pairing events between a target DNA strand and either the pegRNA or the pegRNA-derived flap, each of which provides an opportunity to reject an off-target sequence without modification 24,28,42,43,44,45, 46,47,48,49,50. We assessed off-target prime editing outcomes from our HBBS correction strategy in CD34+ cells. We used the experimental genome-wide off-target identification method CIRCLE-seq51 to nominate potential off-target loci engaged by the Cas9 domain and guide RNAs used in the prime editing experiments above, then measured off-target editing by HTS of the nominated sites in prime-edited HSPCs from SCD patient donors. Since Cas9 nuclease activity when complexed with epegRNAs is modestly decreased compared with Cas9 with the corresponding sgRNA26, we performed CIRCLE-seq using the optimized epegRNA, using a sgRNA surrogate containing the identical protospacer, or using the NG1 nicking sgRNA.

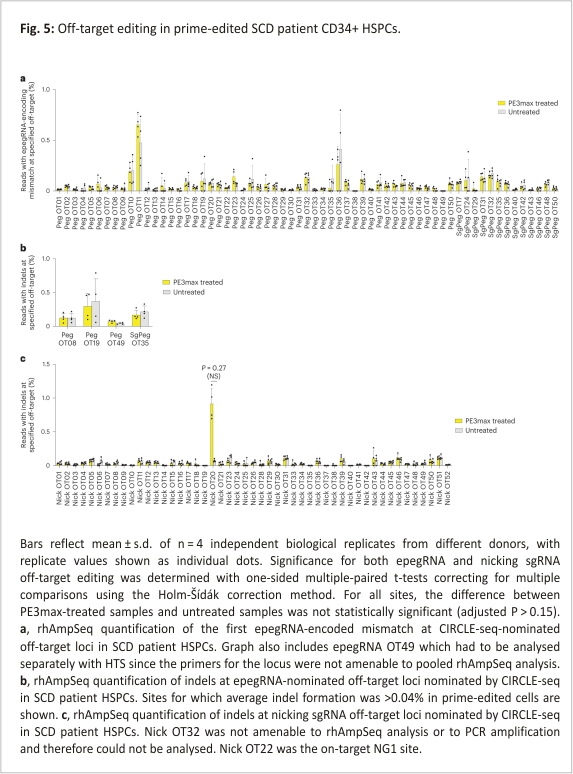

CIRCLE-seq nominated 515 off-target sites when using the epegRNA, 437 sites when using a sgRNA with the epegRNA spacer, and 281 sites when using the nicking sgRNA (Supplementary Tables 9–11). Because a large fraction of sites nominated by CIRCLE-seq is false positives51, the remaining 78 loci nominated when using the epegRNA but not when using the surrogate sgRNA are probably false positives. We used RNase H-dependent amplification and sequencing (rhAmpSeq) to perform multiplex-targeted DNA sequencing of the top 50 sites for each of these three categories, excluding the on-target sites and sites not amenable to pooling with the other loci (Supplementary Table 12). Only 13 of the top 50 sites nominated using the surrogate sgRNA version of the epegRNA were not also nominated in the top 50 sites using the epegRNA. All 13 were within the top 173 sites for the epegRNA. In total, from the epegRNA and surrogate sgRNA CIRCLE-seq results, we examined in depth 63 nominated off-target candidates, including the top 50 sites from both lists.

To assess off-target editing at CIRCLE-seq-detected sites of engagement by Cas9·epegRNA or Cas9·surrogate sgRNA complexes, we quantified the mutation frequency at the position of the first nucleotide change that would be introduced by the epegRNA RTT at each off-target site (Extended Data Fig. 4a). This position is the most likely nucleotide to be modified during prime editing24. Additionally, we quantified the indel frequency at the nominated epegRNA sites. One nominated off-target site, pegOT49, was not compatible with rhAmpSeq amplification and was analysed separately. We detected no epegRNA-dependent off-target prime editing in treated cells compared with untreated controls at any of the 63 CIRCLE-seq-nominated sites (Fig. 5a,b). This high degree of DNA specificity is consistent with previous reports of low off-target prime editing and probably arises from the three distinct DNA hybridization events that must take place to result in productive prime editing24,28,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50.

To determine off-target editing at CIRCLE-seq-nominated off-target sites for the nicking sgRNA, we attempted to quantify the frequency of indels at the top 50 sites. One nominated off-target site, Nick OT32, was not compatible with rhAmpSeq or PCR amplification and could not be analysed. Among the remaining 49 loci, the highest observed level of any editing (averaging 0.91%) was at Nick OT20, a genomic site that contains the identical protospacer targeted by NG1. This level of editing was not statistically significant (P = 0.27) in treated cells compared to untreated controls when analysed using one-sided paired multiple comparison t-tests correcting for multiple comparisons using the Holm-Šídák method (Fig. 5c). Nick OT20 is found in HBD, a lowly expressed β-globin gene located 7.4 kb from HBB on chromosome 11. We used droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) to assess the potential deletion between the on-target locus and Nick OT20. Less than 1% of genomes isolated from healthy donor HSPCs treated with 2xPE3max + NG1 contained this deletion (Extended Data Fig. 4b). This deletion was not detected when NG1 nicking sgRNA was replaced with the PE3b nicking sgRNA (NG2), consistent with the PE3b strategy of avoiding the presence of simultaneous nicks on opposite DNA strands24.

Collectively, the analysis of prime-edited HSPCs at a total of 112 CIRCLE-seq-nominated candidate off-target sites engaged by Cas9 complexed with the HBBS-targeting epegRNA or a corresponding sgRNA detected minimal off-target editing. Off-target indel formation for Cas9 nuclease complexed with NG1 nicking sgRNA also resulted in minimal indel formation. Although it was not statistically validated as a bona fide off-target locus, the nominated Nick OT20 site contains the same NG1 protospacer sequence that occurs within the HBD gene encoding haemoglobin delta, which makes up only 3% of adult globin content52; we also detected a rare (<1%) deletion of the intervening DNA between the on-target locus and the Nick OT20 site. The PE3b nicking sgRNA has a spacer sequence that does not match any sequence in HBD or any other region of human genome sequence hg38, and no deletion between HBB and Nick OT20 was detected in cells prime edited using the PE3b nicking sgRNA. Overall, these findings suggest that the prime editing strategy used to correct HBBS causes minimal off-target edits in the human genome.

Discussion

Advancements in genome editing technologies have provided many options for treating SCD. While the best strategy has not yet been determined and multiple strategies may offer clinical benefit, reverting the SCD allele back to wild type is the most physiological approach. Correction strategies using nuclease-initiated HDR face several challenges including donor DNA template delivery, perturbation of engraftment potential14,23, and low ratios of desired editing to indel by-products12,14. We describe a prime editing strategy that directly corrects the SCD allele to wild-type HBBA without requiring double-strand DNA breaks, viral transduction, or any donor DNA templates. Following extensive optimization of key parameters including the choice of PE3max, the design of the pegRNA, the total volume of RNAs electroporated, and the position of the nicking guide, our strategy yields up to 41% prime editing in SCD patient HSPCs by day 3, which was maintained in bone-marrow-repopulating HSCs in transplanted mice after 17 weeks. RBCs derived from repopulated HSCs after prime editing and transplantation in mice showed a reduction in HbS and sickling and a rise in HbA proportional to on-target editing. Ratios of HBBS reversion to indels were high, and off-target editing was minimal after investigating 112 CIRCLE-seq-nominated candidate off-target sites.

There are several autologous transplantation approaches being developed or in clinical trials toward a treatment for SCD3,4,5,6,10,13,22, and it is not yet known which strategy will be the safest and most effective for patients. The prime editing strategy developed in this work offers several potential advantages. It directly eliminates the pathogenic HBBS allele and converts it back to the wild-type allele, in contrast with strategies that rely on the lentiviral expression of non-sickling globin or induction of HbF.

Current strategies to correct HBBS in SCD patient HSCs include nuclease-initiated HDR electroporated with wild-type or a high-fidelity Cas9 nuclease complexed with a chemically modified sgRNA and a donor DNA template either delivered as single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide donor12 or through recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 6 (rAAV6)-mediated delivery14. Compared to non-viral donor template delivery12, the prime editing strategy developed in this study leads to similar levels of desired correction in patient HSCs with a much higher desired edit-to-indel ratio and far fewer off-target indels. Similarly, compared with an HDR strategy that uses rAAV6-mediated donor template delivery14, the prime editing strategy described here results in a higher desired edit-to-indel ratio and more efficient targeting of long-term HSCs with similar levels of pre-transplantation and post-transplantation HBBS-to-HBBA correction. Our untreated control patient HSCs engrafted at the same level as prime-edited patient HSCs. In contrast, HSCs with rAAV6-delivered donor templates engrafted significantly less efficiently than mock-electroporated cells14, consistent with a recent report that long-term HSCs engraft more poorly following HDR editing with rAAV6-delivered donor templates23. These observations suggest that prime-edited HSCs engraft at higher rates, although a well-controlled study is needed to account for any confounding variables.

Another important advantage of the prime editing strategy described here is that it does not require DSBs, although low frequencies of DSBs from staggered nicks can occur. These DSB frequencies can be virtually eliminated with a PE3b strategy that prevents simultaneous nicking of opposite DNA strands. Compared with nuclease-dependent approaches, prime editing greatly reduces the likelihood of undesired DSB outcomes such as uncontrolled and uncharacterized mixtures of indels, which in HBB can lead to β-thalassaemia-like loss-of-function12,14. The upper limit of tolerable indel by-products at HBB in the context of SCD gene correction is unknown. However, HDR-based approaches with high levels of indels may cause β-thalassemia-like pathophysiology in erythroid precursors, with deficiency of β-globin protein, accumulation of toxic free α-globin, maturation arrest, and apoptosis12,53,54. A high edit-to-indel ratio as achieved with editing methods that do not require DSBs maximizes the number of precisely corrected cells administered to patients. In comparison with nuclease-dependent approaches, prime editing also reduces the likelihood of large deletions, chromosomal loss, translocations, chromothripsis, and other undesired cell state changes15,16,17,18,19. Several studies have used whole-genome sequencing, whole-transcriptome sequencing, and other broad analytical methods following prime editing to assess potential genome- or transcriptome-wide changes in mammalian cells and, thus far, neither changes in single-nucleotide variants, indels, telomere length, endogenous retrotransposon activity, gene expression or splicing nor any off-target RNA editing have been reported45,46,48,49,50.

An additional feature of the prime editing strategy studied here is that it does not require DNA delivery, viral transduction, or drug selection to enrich edited cells. DNA delivery is required for HDR and gene therapy, but can also lead to increased toxicity, lower engraftment frequency, or insertional mutagenesis 14,21,23,55,56,57.

We compared CIRCLE-seq off-target site nomination using a sgRNA containing the epegRNA spacer sequence to CIRCLE-seq using the epegRNA directly. The overlap between top hits was substantial. On the basis of the overlap and the CIRCLE-seq methodology, we suggest that either guide RNA form could be used in future assessments of off-target prime editing. Of the 112 candidate off-target sites that we assessed with HTS, only one site (Nick OT20) showed off-target editing consistently above that of untreated cells. While the observed level of off-target editing at Nick OT20 (0.91%) was not statistically significant, this candidate off-target site contains an identical protospacer sequence to the nicking sgRNA.

Converting HBBS to the benign naturally occurring β-globin Makassar (HBBG) variant with an adenine base editor13,58 also offers advantages over Cas nuclease-based approaches and occurs more efficiently with fewer indels than reverting HBBS to HBBA with PE3max13,58. However, the prime editing approach generates the natural adult β-globin allele and produces fewer off-target edits than previously described HBBS-to-HBBG adenine base editing13,58. Cas-independent off-target editing of DNA or RNA can occur with some base editors59,60,61 but was not detected with prime editing in several studies that investigated this possibility 24,28,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50. Because base editing and prime editing each have unique advantages, it is not yet clear which of the two might be a more promising strategy for SCD patients.

Future studies that combine more efficient PEs with the PE3b nicking sgRNA may further increase ratios of prime editing to indels. Additionally, alternative delivery modalities may be beneficial for maintaining cell viability and reducing off-target editing. For example, compared with the delivery of genome editing agents as mRNA, ribonucleoprotein is associated with shorter-expression times of Cas9 and base editors, resulting in reduced off-target editing13,62,63. This trend will probably hold true for PEs. Additionally, electroporation can reduce HSPC viability, requiring a higher number of starting cells to be edited. Thus, the use of engineered virus-like particles64 or other non-viral delivery methods that do not require electroporation may further the therapeutic potential of genome editing approaches, including prime editing, by (1) reducing the toxicity of ex vivo gene modification and (2) raising the possibility of in vivo delivery modalities that obviate the need for HSC collection and transplantation.

The ex vivo mRNA delivery method used in this study is similar to current methods used for HSC editing in clinical trials6,7,32. Following extensive protocol optimization that may be applicable to PE correction of other pathogenic alleles, we achieved high levels of correction of HBBS in SCD patient cells. With a single electroporation, cells could be efficiently edited and cryopreserved. After being injected upon thawing to minimize loss of multipotency in vitro, edited cells efficiently engrafted into animal recipients with no loss of target prime editing efficiency after 17 weeks. The observed reduction in HbS levels, increase in HbA levels and reduction in sickling propensity are suggestive of exceeding the predicted levels required for therapeutic benefit in SCD patients40,41. These findings are among the first to establish therapeutic prime editing of HSCs, collectively suggesting that prime editing and transplanting patient HSPCs may represent a promising therapeutic strategy as a one-time autologous treatment for SCD.

Methods

HTS

HTS of genomic DNA extracted from human CD34+ cells was performed as previously described13. Genomic DNA was isolated from cells using lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.05% SDS, 25 μg ml−1 proteinase K (ThermoFisher). Lysed genomic DNA was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h, followed by heat inactivation at 80 °C for 30 min. Primers for amplification of the DNMT1, HEK3, RNF2, RUNX1, and HBB loci are provided in Supplementary Table 1. Primers include adapters for Illumina sequencing. Following Illumina barcoding, PCR products were pooled and purified by electrophoresis with a 2% agarose gel and a QIAquick Gel Extraction kit (Qiagen), eluting with 30 µl of warm water. DNA concentration was determined using a Qubit dsDNA High-Sensitivity Assay kit (ThermoFisher) and sequencing was done on an Illumina MiSeq instrument (single-end read, 280 cycles) according to manufacturer protocols. Alignment of fastq files and quantification of editing frequency was performed using CRISPResso2 in batch mode with a window width spanning at least 10 nt past each nick site.

PE, PEmax, and MLH1dn mRNA in vitro transcription

In vitro, transcription of PE2 and PEmax mRNA was performed as previously described25,26. Briefly, the 5′ untranslated region, Kozak sequence, PE2 or PEmax open-reading frame, and 3′ untranslated region were cloned into a plasmid containing an inactive T7 (dT7) promoter. The mRNA transcription template was generated via PCR with primers that correct the dT7 promoter sequence and install a poly(A) tail. The mRNA was transcribed using the T7 High-Yield RNA kit (New England Biolabs) according to manufacturer instructions, except for the full substitution of N1-methyl pseudouridine (Trilink) for uridine and co-transcriptional capping with CleanCap AG (Trilink). The resulting mRNA was purified via lithium chloride precipitation and resuspended in TE buffer (10 nM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0 at room temperature). MLH1 dominant negative mRNA (MLH1dn) was transcribed analogously.

Synthetic epegRNA and nicking single-guide RNA generation

Synthetic epegRNAs were ordered from Integrated DNA Technologies. Each contained 2′-O-methyl modifications at the first and last three nucleotides and phosphorothioate linkages between the three first and last nucleotides. For all epegRNAs except when explicitly noted, the pegLIT algorithm was used as previously described26 to design linkers. Synthetic nicking sgRNAs were obtained from Synthego and included 2′-O-methyl modifications at the first and last three bases as well as phosphorothioate bonds between the first three and last two bases.

Isolation and culture of CD34+ human HSPCs

Circulating G-CSF-mobilized human mononuclear cells were obtained from deidentified healthy adult donors (Fred Hutchinson Research Center). Plerixafor-mobilized CD34+ cells or collected bone marrow from deidentified SCD patient donors were collected according to the protocol ‘Peripheral blood stem cell collection for SCD patients’ (Clinical Trials.gov identifier NCT03226691), which was approved by the human subject research institutional review boards at the National Institutes of Health and St Jude Children’s Research Hospital. HSPCs were maintained in stem cell culture media: X-VIVO-15 (Lonza, 04-418Q) media supplemented with 100 ng µl−1 human SCF (R&D systems, 255-SC/CF), 100 ng µl−1 human TPO (R&D systems, 288-TP/CF) and 100 ng µl−1 human Flt-3 ligand (R&D systems, 308-FK/CF). Cells were seeded and maintained at a density of 1–2 × 106 cells per ml.

PE electroporation of human HSPC

Electroporations were performed with the Lonza 4D Nucleofector system using the programme DS-130. All electroporations were performed in 20 µl reactions using the P3 Primary Cell X Kit S (Lonza, V4XP) with 15 μl of supplemented P3 buffer according to manufacturer instructions. For a standard PE3 electroporation, 1,000 ng of in vitro-transcribed PEmax mRNA was mixed with 90 pmol of synthetic epegRNA and 60 pmol of synthetic nicking sgRNA in 2 μl. For PE4 and PE5 electroporations, 1,000 ng of in vitro-transcribed codon-optimized MLH1dn mRNA in 0.5 μl was also used. The 0.5 μl increase in volume is unlikely to negatively affect editing outcomes. For electroporations in which either the PEmax mRNA, the guide RNAs or both had increased concentrations, we increased the concentrations without increasing the standard volume of 2 μl. For 2xPE3max, 3xPE3max, and 4xPE3max electroporations, we increased the volume of the editing reagents to 4 μl, 6 μl, or 8 μl while keeping the standard concentrations. We thawed cells and allowed them to recover in X-VIVO 15 cytokine-supplemented media for 1 d before electroporation. We electroporated 5 × 105 to 1 × 106 cells per reaction and cultured them at a density of 2 × 106 cells per ml. For SCD patient HSPCs to be transplanted into NBSGW mice, we cryopreserved the cells at 1 d post-electroporation. All epegRNA and nicking sgRNA sequences can be found in Supplementary Table 2. For electroporations with siRNAs (Extended Data Fig. 1b), 1.875 μl 100 μM pooled siRNAs (Horizon, MLH1-targeting L-003906-00-0005 or non-targeting D-001810-10-05) were electroporated per condition with 1,000 ng of in vitro-transcribed PE mRNA, 90 pmol of synthetic epegRNA and 60 pmol of synthetic NG1 nicking sgRNA.

Cryopreservation of edited HSPCs

Edited cells (1 × 106 to 2 × 106) were allowed to recover in cytokine-supplemented X-VIVO 15 media for 1 d before cryopreservation. Cell pellets were collected and resuspended in equal volumes of Plasma-lyte-A media (Baxter) supplemented with 25% human serum albumin (Grifols Biologicals) and pentastarch media (Preservation Solutions) supplemented with DMSO (ATCC).

Ethical approval for studies involving mice

Mouse studies were approved by the St Jude Children’s Research Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee under Protocol 579 entitled ‘Genetic models for the study of hematopoiesis’. Mice were cared for by staff at the St Jude Children’s Research Hospital Animal Resource Center according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health.

Mouse experiments

No statistical test was used to predetermine the sample size. All recipient mice were randomly selected for transplantation conditions by an animal facility staff member who blindly determined which mice would receive which cells. Investigators were also blinded to the conditions of identification numbers assigned to each mouse. All assays were performed before identification numbers were matched to each experimental group.

Transplantation of gene-edited CD34+ HSPCs

Gene-edited CD34+ HSPCs were transplanted into NOD.Cg-KitW- 41J Tyr+ Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/ThomJ (NBSGW) mice.

Transplantation experiments were performed as previously described13 with the following exception: cryopreserved cells were thawed, counted, and immediately injected into recipients. All antibodies used in the study can be found in Supplementary Table 8.

Erythroid culture

Erythroid differentiation was completed as previously described13.

Colony forming assay and analysis of clonal editing outcomes

BFU-E assays were performed and analyzed as previously described13.

Haemoglobin quantification

Haemoglobin was quantified via HPLC using ion exchange columns as previously described13.

In vitro sickling assay

The in vitro sickling assay was performed as previously described13. Briefly, erythroid cells were seeded into 96-well plates with 100 µl of phase 3 erythroid differentiation medium under hypoxic conditions (2% oxygen) for 24 h. Cells were monitored for 8 h with the IncuCyte S3 Live-Cell Analysis system and images of the cells were taken at ×20 objective. A blinded researcher quantified sickling under each condition by counting over 300 cells per condition.

CIRCLE-seq off-target editing analysis

CIRCLE-seq off-target nomination and analysis were conducted as previously described13. All CIRCLE-seq-nominated sites can be found in Supplementary Tables 9–11.

Targeted off-target amplicon sequencing and analysis by rhAmpSeq

Off-target sites nominated by CIRCLE-seq were amplified from PE3max-treated or untreated HSPCs from sickle-cell donors at 3 d post-electroporation using the rhAmpSeq system (IDT). A pooled sequencing library was generated using the rhAmpSeq design tool (primers listed in Supplementary Table 12). Genomic DNA was amplified using the pooled library according to manufacturer instructions and sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq instrument (single-end read, 270 cycles).

For epegRNA off-target analysis, we quantified the percentage of mismatches that could be encoded by the epegRNA and the percentage of indels at the top 63 CIRCLE-seq-nominated loci. For nicking sgRNA off-target analysis, we quantified the percentage of indels at the top 49 CIRCLE-seq-nominated loci. The code for each analysis can be found at https:// github.com/YichaoOU/PE_off_target. Both epegRNA OT49 and Nick OT32 were not compatible with the pooled rhAmpSeq analysis. EpegRNA OT49 was analysed via HTS with forward primer 5′-ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGAT CTNNNNTGGGTGTTATGGCCATCATGA-3′ and reverse primer 5′-TGGAGTTCA GACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTCCTCAACAAA CTGAGGCATAC-3′. Nick OT32 could not be analysed because it was not amenable to PCR amplification.

ddPCR assay

The ddPCR assay was performed as previously described29 in crude genomic DNA from unedited 2xPE3max + NG1-treated or 2xPE3max + NG2-treated HSPCs from healthy donors using ACTB (Bio-Rad, dHsaCNS141996500) as the reference gene. The primers used to determine the abundance of the 7.4 kb deletion between HBB and HBD were 5′-GCAAAGTG AACGTGGATGC-3′ and 5′-AAACCC AAGAGTCTTCTCTGTC-3′, and the probe sequence was 5′-AGGAGACCAATAGAAA CTGGGCATGTG-3′.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data supporting the results of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information. High-throughput sequencing data are available from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive database (PRJNA915048). Key plasmids are available from Addgene (depositor: D.R.L.), or from the corresponding authors on request. Source data for the figures are provided in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank the SCD patients who donated samples for this study; D. Gao and other members of our laboratories for insightful discussions; A. Vieira for helpful science communication advice and M. O’Reilly for help with figure design. Allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated anti-Band3 was a gift from X. An (New York Blood Center). This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health awards U01 AI142756, RM1 HG009490 and R35 GM118062 (D.R.L.), R01 HL156647 and R01 HL136135 (M.J.W. and D.R.L), the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (D.R.L. and M.J.W.), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (D.R.L.), P01 HL053749 (M.J.W.) and the St Jude Collaborative Research Consortium for Sickle Cell Disease (M.J.W., J.S.Y., and D.R.L.). K.A.E, A.A.S., and P.J.C. acknowledge NSF GRFP fellowships. G.A.N. was supported by a Helen Hay Whitney Postdoctoral Fellowship and the HHMI. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, and analysis, the decision to publish, or the preparation of the manuscript. We also thank the following core facilities and individuals at St Jude Children’s Research Hospital: Flow Cytometry (R. Ashmun and S. Woolard), and Animal Resource Center (C. Savage). The St Jude Children’s Research Hospital core facilities are supported by NIH grant P30 CA21765 and by St Jude/ALSAC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Merkin Institute of Transformative Technologies in Healthcare, Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, Cambridge, MA, USA

Kelcee A. Everette, Gregory A. Newby, Jessie R. Davis, Andrew T. Nelson, Peter J. Chen, Alexander A. Sousa & David R. Liu

Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA

Kelcee A. Everette, Gregory A. Newby, Jessie R. Davis, Andrew T. Nelson, Peter J. Chen, Alexander A. Sousa & David R. Liu

Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA

Kelcee A. Everette, Gregory A. Newby, Jessie R. Davis, Andrew T. Nelson, Peter J. Chen, Alexander A. Sousa & David R. Liu

Department of Hematology, St Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN, USA

Rachel M. Levine, Kalin Mayberry, Yoonjeong Jang, Thiyagaraj Mayuranathan, Nikitha Nimmagadda, Erin Dempsey, Yichao Li, Senthil Velan Bhoopalan, Yong Cheng, Mitchell J. Weiss & Jonathan S. Yen

Molecular and Clinical Hematology Branch, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA

Xiong Liu & John F. Tisdale

Contributions

K.A.E, G.A.N., R.M.L., K.M., E.D., Y.L., Y.J., T.M., N.N., S.V.B., and J.S.Y. conducted experiments and analysed the data. X.L., J.R.D., A.T.N., P.J.C., A.A.S., Y.C., J.F.T. and M.J.W. provided materials and assistance. K.A.E. and D.R.L. wrote the paper, with input from all authors. J.S.Y. and D.R.L. supervised the study.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Jonathan S. Yen or David R. Liu.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have filed patent applications on prime editing through the Broad Institute (Cambridge, MA). D.R.L. is a consultant and equity owner of Prime Medicine, Beam Therapeutics, Pairwise Plants, Nvelop Therapeutics, and Chroma Medicine, companies that use or deliver genome editing or epigenome-modulating agents. M.J.W. is a consultant for GSK plc, Cellarity Inc., Novartis, and Dyne Therapeutics. J.S.Y is an equity owner of Beam Therapeutics. J.R.D. and P.J.C. are currently employees of Prime Medicine. The other authors declare no competing interests

Code availability

The code used to conduct off-target quantification and statistical analysis can be found at https://github.com/YichaoOU/ PE_off_target.

References

1. Piel, F. B., Steinberg, M. H. & Rees, D. C. Sickle cell disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 376, 1561–1573 (2017).

2. Khemani, K., Katoch, D. & Krishnamurti, L. Curative therapies for sickle cell disease. Ochsner J. 19, 131–137 (2019).

3. Kanter, J. et al. Biologic and clinical efficacy of lentiglobin for sickle cell disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 617– 628 (2022).

4. Zeng, J. et al. Therapeutic base editing of human hematopoietic stem cells. Nat. Med. 26, 535–541 (2020).

5. Esrick, E. B. et al. Post-transcriptional genetic silencing of BCL11A to treat sickle cell disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 205–215 (2021).

6. Frangoul, H. et al. CRISPR–Cas9 gene editing for sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 252–260 (2021).

7. Lessard, S. et al. Zinc finger nuclease-mediated disruption of the BCL11A erythroid enhancer results in enriched biallelic editing increased fetal hemoglobin, and reduced sickling in erythroid cells derived from sickle cell disease patients. Blood 134, 974–974 (2019).

8. Traxler, E. A. et al. A genome-editing strategy to treat β-hemoglobinopathies that recapitulates a mutation associated with a benign genetic condition. Nat. Med. 22, 987–990 (2016).

9. Métais, J.-Y. et al. Genome editing of HBG1 and HBG2 to induce fetal hemoglobin. Blood Adv. 3, 3379– 3392 (2019).

10. Wilkinson, A. C. et al. Cas9-AAV6 gene correction of beta-globin in autologous HSCs improves sickle cell disease erythropoiesis in mice. Nat. Commun. 12, 686 (2021).

11. Yao, S. Graphite bio announces voluntary pause of phase ½ CEDAR study of nulabeglogene autogedtemcel (nulla-cel) for sickle cell disease. Businesswire (5 January 2023).

12. Magis, W. et al. High-level correction of the sickle mutation is amplified in vivo during erythroid differentiation. iScience 25, 104374 (2022).

13. Newby, G. A. et al. Base editing of haematopoietic stem cells rescues sickle cell disease in mice. Nature 595, 295– 302 (2021).

14. Lattanzi, A. et al. Development of β-globin gene correction in human hematopoietic stem cells as a potential durable treatment for sickle cell disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 13, eabf2444 (2021).

15. Zuccaro, M. V. et al. Allele-specific chromosome removal after Cas9 cleavage in human embryos. Cell 183, 1650–1664.e15 (2020).

16. Enache, O. M. et al. Cas9 activates the p53 pathway and selects for p53-inactivating mutations. Nat. Genet. 52, 662–668 (2020).

17. Ihry, R. J. et al. p53 inhibits CRISPR– Cas9 engineering in human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Med. 24, 939–946 (2018).

18. Kosicki, M., Tomberg, K. & Bradley, A. Repair of double-strand breaks induced by CRISPR–Cas9 leads to large deletions and complex rearrangements. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 765–771 (2018).

19. Haapaniemi, E., Botla, S., Persson, J., Schmierer, B. & Taipale, J. CRISPR– Cas9 genome editing induces a p53-mediated DNA damage response. Nat. Med. 24, 927–930 (2018).

20. Ferrari, S. et al. The choice of template delivery mitigates the genotoxic risk and adverse impact of editing in human hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 29, 1428–1444.e9 (2022).

21. Schiroli, G. et al. Precise gene editing preserves hematopoietic stem cell function following transient p53-mediated DNA damage response. Cell Stem Cell 24, 551–565.e8 (2019).

22. Dever, D. P. et al. CRISPR–Cas9 β-globin gene targeting in human haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 539, 384–389 (2016).

23. Romero, Z. et al. Editing the sickle cell disease mutation in human hematopoietic stem cells: comparison of endonucleases and homologous donor templates. Mol. Ther. 27, 1389–1406 (2019).

24. Anzalone, A. V. et al. Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Nature 576, 149–157 (2019).

25. Chen, P. J. et al. Enhanced prime editing systems by manipulating cellular determinants of editing outcomes. Cell 184, 5635–5652.e29 (2021).

26. Nelson, J. W. et al. Engineered pegRNAs improve prime editing efficiency. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 402–410 (2022).

27. Chen, P. J. & Liu, D. R. Prime editing for precise and highly versatile genome manipulation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 24, 161–177 (2022).

28. Jin, S. et al. Genome-wide specificity of prime editors in plants. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 1292–1299 (2021).

29. Anzalone, A. V. et al. Programmable deletion, replacement, integration, and inversion of large DNA sequences with twin prime editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 731–740 (2022).

30. Choi, J. et al. Precise genomic deletions using paired prime editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 218–226 (2022).

31. Lin, Q. et al. High-efficiency prime editing with optimized, paired pegRNAs in plants. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 923–927 (2021).

32. De Dreuzy, E. et al. EDIT-301: an experimental autologous cell therapy comprising Cas12a-RNP modified mPB-CD34+ cells for the potential treatment of SCD. Blood 134, 4636 (2019).

33. Ferreira da Silva, J. et al. Prime editing efficiency and fidelity are enhanced in the absence of mismatch repair. Nat. Commun. 13, 760 (2022).

34. Li, C. et al. In vivo HSC prime editing rescues sickle cell disease in a mouse model. Blood https://doi.org/10.11 82/ blood.2022018252 (2023).

35. Peterson, C. W. et al. Intracellular RNase activity dampens zinc finger nuclease-mediated gene editing in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 24, 30–39 (2022).

36. Leonard, A. et al. Low-dose busulfan reduces human CD34+ cell doses required for engraftment in c-kit mutant immunodeficient mice. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 15, 430–437 (2019).

37. McIntosh, B. E. et al. Nonirradiated NOD, B6.SCID Il2rγ−/− Kit(W41/W41) (NBSGW) mice support multilineage engraftment of human hematopoietic cells. Stem Cell Rep. 4, 171–180 (2015).

38. Luc, S. et al. Bcl11a deficiency leads to hematopoietic stem cell defects with an aging-like phenotype. Cell Rep. 16, 3181–3194 (2016).

39. Kurup, S. P., Moioffer, S. J., Pewe, L. L. & Harty, J. T. p53 hinders CRISPR– Cas9-mediated targeted gene disruption in memory CD8 T cells in vivo. J. Immunol. 205, 2222–2230 (2020).

40. Fitzhugh, C. D. et al. At least 20% donor myeloid chimerism is necessary to reverse the sickle phenotype after allogeneic HSCT. Blood 130, 1946– 1948 (2017).

41. Walters, M. C. et al. Stable mixed hematopoietic chimerism after bone marrow transplantation for sickle cell anemia. Biol. Blood Marrow Transpl. 7, 665–673 (2001).

42. Schene, I. F. et al. Prime editing for functional repair in patient-derived disease models. Nat. Commun. 11, 5352 (2020).

43. Kim, D. Y., Moon, S. B., Ko, J.-H., Kim, Y.-S. & Kim, D. Unbiased investigation of specificities of prime editing systems in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 10576–10589 (2020).

44. Liu, Y. et al. Efficient generation of mouse models with the prime editing system. Cell Discov. 6, 27 (2020).

45. Geurts, M. H. et al. Evaluating CRISPR-based prime editing for cancer modeling and CFTR repair in organoids. Life Sci. Alliance 4, e202000940 (2021).

46. Park, S.-J. et al. Targeted mutagenesis in mouse cells and embryos using an enhanced prime editor. Genome Biol. 22, 170 (2021).

47. Gao, P. et al. Prime editing in mice reveals the essentiality of a single base in driving tissue-specific gene expression. Genome Biol. 22, 83 (2021).

48. Lin, J. et al. Modeling a cataract disorder in mice with prime editing. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 25, 494–501 (2021).

49. Habib, O., Habib, G., Hwang, G.-H. & Bae, S. Comprehensive analysis of prime editing outcomes in human embryonic stem cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, 1187–1197 (2022).

50. Gao, R. et al. Genomic and transcriptomic analyses of prime editing guide RNA-independent off-target effects by prime editors. CRISPR J. 5, 276–293 (2022).

51. Tsai, S. Q. et al. CIRCLE-seq: a highly sensitive in vitro screen for genome-wide CRISPR–Cas9 nuclease off-targets. Nat. Methods 14, 607–614 (2017).

52. Sankaran, V. G. & Orkin, S. H. The switch from fetal to adult hemoglobin. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 3, a011643 (2013).

53. Ribeil, J.-A. et al. Ineffective erythropoiesis in β-thalassemia. Sci. World J. 2013, 394295 (2013).

54. Wu, C. J. et al. Evidence for ineffective erythropoiesis in severe sickle cell disease. Blood 106, 3639–3645 (2005).

55. Pattabhi, S. et al. In vivo, outcome of homology-directed repair at the HBB gene in HSC using alternative donor template delivery methods. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 17, 277–288 (2019).

56. Howe, S. J. et al. Insertional mutagenesis combined with acquired somatic mutations causes leukemogenesis following gene therapy of SCID-X1 patients. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 3143– 3150 (2008).

57. Stein, S. et al. Genomic instability and myelodysplasia with monosomy 7 consequent to EVI1 activation after gene therapy for the chronic granulomatous disease. Nat. Med. 16, 198–204 (2010).

58. Chu et al. Rationally designed base editors for precise editing of the sickle cell disease mutation. CRISPR J. 4, 169–177 (2021).

59. Doman, J. L., Raguram, A., Newby, G. A. & Liu, D. R. Evaluation and minimization of Cas9-independent off-target DNA editing by cytosine base editors. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 620–628 (2020).

60. Jin, S. et al. Cytosine, but not adenine, base editors induce genome-wide off-target mutations in rice. Science 364, 292–295 (2019).

61. Zuo, E. et al. Cytosine base editor generates substantial off-target single-nucleotide variants in mouse embryos. Science 364, 289–292 (2019).

62. Kaczmarek, J. C., Kowalski, P. S. & Anderson, D. G. Advances in the delivery of RNA therapeutics: from concept to clinical reality. Genome Med. 9, 60 (2017).

63. Hendel, A. et al. Chemically modified guide RNAs enhance CRISPR–Cas genome editing in human primary cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 985–989 (2015).

64. Banskota, S. et al. Engineered virus-like particles for efficient in vivo delivery of therapeutic proteins. Cell 185, 250– 265.e16 (2022).

65. Hu, J. et al. Isolation and functional characterization of human erythroblasts at distinct stages: implications for the understanding of normal and disordered erythropoiesis in vivo. Blood 121, 3246–3253 (2013).

Credits: Everette, K.A., Newby, G.A., Levine, R.M. et al. Ex vivo prime editing of patient haematopoietic stem cells rescues sickle-cell disease phenotypes after engraftment in mice. Nat. Biomed. Eng (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-023-01026-0