Kevin Patel1; John E. Hipskind2

Affiliations

1Western Michigan University

2Kaweah Delta Medical Center

As defined by the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology, “(sudden) cardiac arrest is the sudden cessation of cardiac activity so that the victim becomes unresponsive, with no normal breathing and no signs of circulation. If corrective measures are not taken rapidly, this condition progresses to sudden death. Cardiac arrest should be used to signify an event as described above, which is reversed, usually by CPR and/or defibrillation or cardioversion, or cardiac pacing. Sudden cardiac death should not be used to describe events that are not fatal.” This activity describes the evaluation and management of cardiac arrest and reviews the role of the interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of cardiac arrest.

- Review the epidemiology of cardiac arrest.

- Summarize the use of basic life support and advanced life support in the management of cardiac arrest.

- Outline the importance of collaboration and communication among the interprofessional team to enhance the delivery of care in patients with cardiac arrest.

Introduction

As defined by the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology, “(sudden) cardiac arrest is the sudden cessation of cardiac activity so that the victim becomes unresponsive, with no normal breathing and no signs of circulation. If corrective measures are not taken rapidly, this condition progresses to sudden death. Cardiac arrest should be used to signify an event as described above, that is reversed, usually by CPR and/or defibrillation or cardioversion, or cardiac pacing. Sudden cardiac death should not be used to describe events that are not fatal.”1 Each year more than 400,000 Americans succumb to sudden cardiac death.2 Those suffering from cardiac arrest may or may not have been previously diagnosed with heart disease. The cause of cardiac arrest varies by population and age, most commonly occurring in those with a previous diagnosis of heart disease. Most of all cardiac deaths are sudden and usually unexpected, which has proven to be uniformly fatal in the past. However, bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and advances within emergency medical services (EMS) have proven life-saving interventions. Despite this, approximately 10% of those suffering from cardiac arrest leave the hospital alive, most of which are neurologically impaired.3

Etiology

Cardiac arrest is usually due to underlying structural cardiac disease. Seventy per cent of cardiac arrest cases are thought to be due to ischemic coronary disease2, the leading cause of cardiac arrest. Other structural causes include congestive heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, congenital coronary artery abnormalities, arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia, hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy, and cardiac tamponade. Nonstructural cardiac causes include Brugada syndrome, Wolf-Parkinson-White syndrome and congenital long QT syndrome.

There are many non-cardiac etiologies including intracranial haemorrhage, pulmonary embolism, pneumothorax, primary respiratory arrest, toxic ingestions including drug overdose, electrolyte abnormalities, severe infection (sepsis), hypothermia, or trauma.

Epidemiology

Occlusive (ischemic) coronary disease is the leading cause of cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death.4 An initial peak of sudden death occurs from birth to 6 months of age, from sudden infant death syndrome. Incidence is typically very low until reaching a second peak between ages 45 to 75. Interestingly, the most common cause of cardiac death seen in adolescents and young adults mirrors that of middle-aged and older adults.5 Within the United States, up to 70% of all sudden cardiac death is due to underlying coronary heart disease.2

The incidence of cardiac death is lower for women at a younger age when compared to males.6 Despite the lower risk for women, risk factors for occlusive heart disease such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, cigarette smoking, increasing age and family history of the coronary disease continue to predispose to cardiac death, as in males.6

History and Physical

In many patients, warning symptoms may precede a cardiac arrest. However, many times these symptoms are unrecognized or ignored by the individual.7 Many patients who survive cardiac arrest have amnesia, not allowing for the recollection of symptoms before an event. Data obtained from those who did not have amnesia, from family members and/or from those who witnessed the event shows that the most common symptom was chest pain.7 Appropriately, this mirrors the most common presentations of acute coronary ischemia.

An individual found to be in cardiac arrest will be unresponsive, without a pulse, and will not be breathing. A quick head-to-toe assessment will help guide treatment.

Evaluation

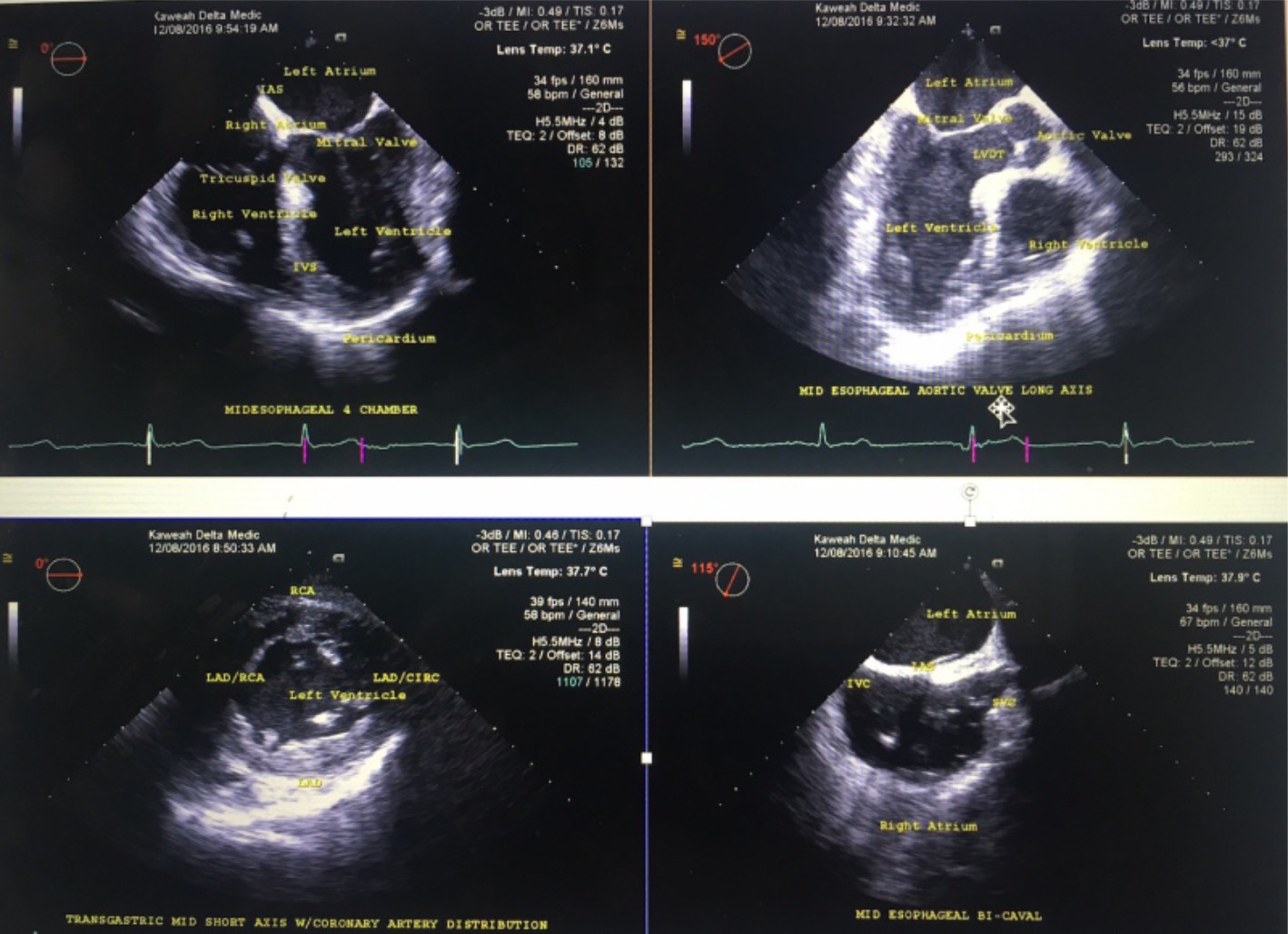

While treating a patient in cardiac arrest, little to no blood or imaging testing is necessary. If one can obtain point-of-care testing, a potassium and glucose level may be beneficial. Point-of-care ultrasound to look for cardiac activity may also be beneficial if it does not interfere with resuscitation efforts.8

Treatment/Management

A patient in cardiac arrest is treated in multiple different stages. The interventions that have proven to reverse cardiac arrest include early CPR and early defibrillation. The initial step involves identification and basic life-support measures. If public access defibrillation is available, it should be activated and utilized if needed. Next, advanced life support measures are used, including intravenous or intraosseous medication administration. If the return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) is obtained, the patient will undergo post-resuscitation care with subsequent long-term management.

Identification of a cardiac arrest victim includes assuring a patient is unresponsive, without central pulses and not breathing normally. Once a victim is identified, immediate CPR and activation of the emergency response system should be of priority. More recently, public access defibrillation has added another layer of response.

Treatment of cardiac arrest depends on the rescuer scope of practice:

Lay Rescuer: Treatment includes hands-only CPR and utilization of AED, if available.9,10 If a patient has had a drowning episode, they can attempt two rescue breaths, since the cause of cardiac arrest is likely from a primary respiratory arrest. If there is no response to rescue breathing, CPR should be initiated. One should continue CPR until the arrival of emergency responders.

Basic Life Support

Treatment for those who are certified to practice basic life support (BLS) includes treatment as above, with the addition of ventilation during active CPR. Current guidelines recommend 2 breaths for every 30 compressions (30:2).9 Providers can also manipulate the airway to aid in airway patency, thus, allowing for proper ventilation. These manoeuvres include the head-tilt, chin-lift11, and jaw thrust12. Oral airway adjuncts including the oral pharyngeal airway (OPA) and the nasopharyngeal airway (NPA) should also be utilized to benefit ventilation.

Advanced Life Support

Providers can use BLS treatment with the addition of medications and advanced airways, including supraglottic airway devices (King LT, Igel) and endotracheal intubation. Medications used in cardiac arrest include Epinephrine and Amiodarone. Advanced life support (ALS) providers have the additional benefit of cardiac rhythm interpretation, allowing for quicker defibrillation if indicated. Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) can teach providers the algorithms used to resuscitate a patient in cardiac arrest.

Physician

Providers can use ALS treatment and progress to a wide scope of practice dependent on medical versus traumatic etiology.

Medical

Medical cardiac arrest patients are treated with ALS as discussed above. These patients can also be placed on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).13 This allows for oxygenation of the victim’s blood supply until the cardiac function is restored.

Trauma

Trauma patients can be divided into blunt (motor vehicle accident) versus penetrating (gun-shot wound). Blunt traumatic arrests are usually secondary to a large vessel injury. Patients usually succumb to their injuries immediately after the event takes place. Most blunt trauma arrest patients are deemed to be futile upon the arrival of first responders. Victims of penetrating trauma are more like to survive when compared to blunt traumatic arrests.14 Penetrating trauma patients are typically treated with bilateral needle decompressions. If ROSC is not obtained and if within a non-futile time frame, patients can undergo a resuscitative thoracotomy. This will allow for direct visualization and, if needed, an intervention of the heart, lungs and large vessels.14 Another technique that is still under evaluation is resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA).15 This involves the placement of an endovascular balloon within the aorta to control haemorrhage, similar to cross-clamping the aorta, which is a manual technique to control haemorrhage during a resuscitative thoracotomy.

Differential Diagnosis

Syncope is a temporary loss of consciousness that is usually caused by decreased blood flow to the brain. Patients who experience syncope are transiently unresponsive as are all individuals experiencing cardiac arrest. However, patients who are in cardiac arrest will not have a normal breathing pattern or a pulse, differentiating syncope from cardiac arrest. A seizure can also be mistaken for cardiac arrest. Patients having a seizure will be unresponsive and will probably have abnormal respirations. Abnormal rhythmic activity and a presence of a pulse differentiate seizure from cardiac arrest. Overdose, particularly from opiates, can lead to a patient who is unresponsive and not breathing normally. The presence of a pulse will differentiate opiate overdose from cardiac arrest.

Prognosis

Factors that are proven to improve survivability include witnessed cardiac arrest with immediate CPR and utilization of defibrillation when indicated.16 Young and healthy patients are more likely to obtain ROSC compared to the elderly and those who have more co-morbidities. Those who are a victim of penetrating trauma have an increased chance of survival than blunt traumatic arrest. Studies have not shown proven benefits for ALS level of care in cardiac arrest, including endotracheal intubation and intravenous (IV) medication administration.17

Complications

Numerous complications can occur during a cardiac arrest. Although not common, the most detrimental complication for a patient in a shockable rhythm is AED failure. Other complications include the inability to obtain IV/IO access. After ROSC, failing to secure and/ or maintain a definitive airway device could lead to a secondary cardiac arrest. During a traumatic etiology, malposition of needle thoracotomy or pericardiocentesis will also lead to complications.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

If ROSC is obtained, the determination to provide targeted temperature management will be made. Candidates for targeted temperature management include those who have a medical etiology, are unresponsive and are stable. Targeted temperature management has been shown to improve mortality and neurological outcomes in patients who have survived a medical cardiac arrest.18

After being stabilized from their cardiac event, the patient’s respiratory status is assessed. If the patient is unable to be successfully extubated, a tracheostomy can be placed to maintain a patent airway. To gain nutrition, a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube is commonly placed.

Patients who require a tracheostomy and PEG tube placement will usually have a prolonged recovery time. These individuals are placed in long-term acute care (LTAC) facilities for care and rehabilitation. Patients who are successfully extubated will still endure a prolonged recovery; however, they are usually more functional.

Consultations

If a cardiac arrest is due to traumatic etiology, trauma surgery is usually consulted to aid with resuscitation, including resuscitative thoracotomy. If ROSC is obtained after a medical cardiac arrest, the emergency room physician will call upon the intensive care team to take care of the patient. If the medical cardiac arrest is deemed secondary to a primary cardiac etiology, cardiology should be consulted to see what intervention is appropriate.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Most cardiac arrests occur in an out-of-hospital setting. Since immediate CPR and utilization of the AED are the 2 main interventions shown to aid in patient outcome,19,20 one can see why training laypersons with adequate CPR skills can be life-saving. Despite training, there continues to be a hesitancy to initiate lay rescuer CPR.21 This could be due to a lack of cardiac arrest recognition, lack of encouragement, or lack of confidence. The patient may also be unreachable or unmovable by the lay rescuer, hindering optimal performance.

Pearls and Other Issues

In hopes to potentially delay cardiac arrest within the general population, one can undergo risk stratification to identify those who may benefit from certain interventions, including a stress

test and screening ECG.

Clinicians should educate the patient about the benefits of daily exercise,22 a healthy diet, effective treatment of hypercholesterolemia, effective treatment of hypertension, effective treatment of diabetes and smoking cessation23 Patients with post-myocardial infarction and who have been diagnosed congestive heart failure can benefit from medication specific medication adjustment, including the addition of beta-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Select patients can also benefit from ICD implantation.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The majority of patients who have cardiac arrest have underlying coronary artery disease. Alteration of modifiable risk factors and medication adjustment can delay the onset of coronary heart disease, potentially delaying cardiac arrest. Despite the many treatments available for cardiac arrest, the majority of patients have a poor prognosis. However, many lives can still be saved with the basic, the most important interventions, including defibrillation and bystander CPR. Promotion of such education to loved ones and others interested can be lifesaving.

All clinicians who see patients should be familiar with the basic principles of resuscitation of a patient that has just been arrested. In the hospital, the resuscitation is carried by an interprofessional team that attends all cardiac arrest events. Outside the hospital, the resuscitation may be carried out by the public or a healthcare worker. In each case, there has to be some in charge and running the resuscitation process. In the hospital, nurses are responsible for bringing the equipment to the patient’s room and documenting the event. In all cases, everyone has an assigned role so that the resuscitation is undertaken without delay. Unfortunately, despite optimal resuscitation, most patients have a poor outcome or do not make it. Those who survive a near-fatal arrest are monitored in the ICU.

In hopes to potentially delay cardiac arrest within the general population, one can undergo risk stratification to identify those who may benefit from certain interventions, including a stress test and screening ECG.

Clinicians should educate the patient about the benefits of daily exercise,22 a healthy diet, effective treatment of hypercholesterolemia, effective treatment of hypertension, effective treatment of diabetes and smoking cessation23 Patients with post-myocardial infarction and who have been diagnosed congestive heart failure can benefit from medication specific medication adjustment, including the addition of beta-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Select patients can also benefit from ICD implantation.

References

1. Kuller LH. Sudden death–definition and epidemiologic considerations. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1980 Jul-Aug;23(1):1-12.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). State-specific mortality from sudden cardiac death–the United States, 1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002 Feb 15;51(6):123-6.

3. Wong MK, Morrison LJ, Qiu F, Austin PC, Cheskes S, Dorian P, Scales DC, Tu JV, Verbeek PR, Wijeysundera HC, Ko DT. Trends in short- and long-term survival among out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients alive at hospital arrival. Circulation. 2014 Nov 18;130(21): 1883-90.

4. Kannel WB, Doyle JT, McNamara PM, Quickenton P, Gordon T. Precursors of sudden coronary death. Factors related to the incidence of sudden death. Circulation. 1975 Apr;51(4):606-13.

5. Drory Y, Turetz Y, Hiss Y, Lev B, Fisman EZ, Pines A, Kramer MR. Sudden unexpected death in persons less than 40 years of age. Am J Cardiol. 1991 Nov 15;68 (13):1388-92.

6. Kannel WB, Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB, Cobb J. Sudden coronary death in women. Am Heart J. 1998 Aug;136(2): 205-12.

7. Marijon E, Uy-Evanado A, Dumas F, Karam N, Reinier K, Teodorescu C, Narayanan K, Gunson K, Jui J, Jouven X, Chugh SS. Warning Symptoms Are Associated With Survival From Sudden Cardiac Arrest. Ann Intern Med. 2016 Jan 05;164(1):23-9. [PMC free article]

8. Gaspari R, Weekes A, Adhikari S, Noble VE, Nomura JT, Theodoro D, Woo M, Atkinson P, Blehar D, Brown SM, Caffery T, Douglass E, Fraser J, Haines C, Lam S, Lanspa M, Lewis M, Liebmann O, Limkakeng A, Lopez F, Platz E, Mendoza M, Minnigan H, Moore C, Novik J, Rang L, Scruggs W, Raio C. Emergency department point-of-care ultrasound in out-of-hospital and in-ED cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2016 Dec;109: 33-39.

9. Kleinman ME, Brennan EE, Goldberger ZD, Swor RA, Terry M, Bobrow BJ, Gazmuri RJ, Travers AH, Rea T. Part 5: Adult Basic Life Support and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Quality: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2015 Nov 03;132(18 Suppl 2): S414-35.

10. Olasveengen TM, de Caen AR, Mancini ME, Maconochie IK, Aickin R, Atkins DL, Berg RA, Bingham RM, Brooks SC, Castrén M, Chung SP, Considine J, Couto TB, Escalante R, Gazmuri RJ, Guerguerian AM, Hatanaka T, Koster RW, Kudenchuk PJ, Lang E, Lim SH, Løfgren B, Meaney PA, Montgomery WH, Morley PT, Morrison LJ, Nation KJ, Ng KC, Nadkarni VM, Nishiyama C, Nuthall G, Ong GY, Perkins GD, Reis AG, Ristagno G, Sakamoto T, Sayre MR, Schexnayder SM, Sierra AF, Singletary EM, Shimizu N, Smyth MA, Stanton D, Tijssen JA, Travers A, Vaillancourt C, Van de Voorde P, Hazinski MF, Nolan JP., ILCOR Collaborators. 2017 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations Summary. Resuscitation. 2017 Dec;121:201-214.

11. Guildner CW. Resuscitation–opening the airway. A comparative study of techniques for opening an airway obstructed by the tongue. JACEP. 1976 Aug;5(8):588-90. [PubMed]

12. Uzun L, Ugur MB, Altunkaya H, Ozer Y, Ozkocak I, Demirel CB. Effectiveness of the jaw-thrust manoeuvre in opening the airway: a flexible fiberoptic endoscopic study. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2005;67(1):39-44.

13. Younger JG, Schreiner RJ, Swaniker F, Hirschl RB, Chapman RA, Bartlett RH. Extracorporeal resuscitation of cardiac arrest. Acad Emerg Med. 1999 Jul;6(7):700-7.

14. Seamon MJ, Haut ER, Van Arendonk K, Barbosa RR, Chiu WC, Dente CJ, Fox N, Jawa RS, Khwaja K, Lee JK, Magnotti LJ, Mayglothling JA, McDonald AA, Rowell S, To KB, Falck-Ytter Y, Rhee P. An evidence-based approach to patient selection for emergency department thoracotomy: A practise management guideline from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015 Jul;79(1):159-73.

15. Biffl WL, Fox CJ, Moore EE. The role of REBOA in the control of exsanguinating torso haemorrhage. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015 May;78(5):1054-8.

16. de Vreede-Swagemakers JJ, Gorgels AP, Dubois-Arbouw WI, Dalstra J, Daemen MJ, van Ree JW, Stijns RE, Wellens HJ. Circumstances and causes of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in sudden death survivors. Heart. 1998 Apr;79(4):356-61.

17. Stiell IG, Wells GA, Field B, Spaite DW, Nesbitt LP, De Maio VJ, Nichol G, Cousineau D, Blackburn J, Munkley D, Luinstra-Toohey L, Campeau T, Dagnone E, Lyver M., Ontario Prehospital Advanced Life Support Study Group. Advanced cardiac life support in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2004 Aug 12;351(7):647-56.

18. Schenone AL, Cohen A, Patarroyo G, Harper L, Wang X, Shishehbor MH, Menon V, Duggal A. Therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest: A systematic review/meta-analysis exploring the impact of expanded criteria and targeted temperature. Resuscitation. 2016 Nov;108:102-110.

19. Berg RA, Hemphill R, Abella BS, Aufderheide TP, Cave DM, Hazinski MF, Lerner EB, Rea TD, Sayre MR, Swor RA. Part 5: adult basic life support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010 Nov 02;122(18 Suppl 3):S685-705.

20. Zhan L, Yang LJ, Huang Y, He Q, Liu GJ. Continuous chest compression versus interrupted chest compression for cardiopulmonary resuscitation of non-asphyxial out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Mar 27;3:CD010134.

21. Wik L, Kramer-Johansen J, Myklebust H, Sørebø H, Svensson L, Fellows B, Steen PA. Quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation during out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2005 Jan 19; 293(3):299-304.

22. Siscovick DS, Weiss NS, Hallstrom AP, Inui TS, Peterson DR. Physical activity and primary cardiac arrest. JAMA. 1982 Dec 17;248(23):3113-7.

23. Sandhu RK, Jimenez MC, Chiuve SE, Fitzgerald KC, Kenfield SA, Tedrow UB, Albert CM. Smoking, smoking cessation, and risk of sudden cardiac death in women. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012 Dec;5(6):1091-7.

CREDITS

Patel K, Hipskind JE. Cardiac Arrest. [Updated 2021 Aug 11]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534866/