Albert E. Zhou, M.D., Ph.D., and Mark A. Travassos, M.D.

A diagnosis of sickle-cell disease (SCD) portends a lifetime of crises marked by substantial pain, infections, anemia, and increased risk of stroke. Sub-Saharan Africa is home to the majority of people living with SCD. About 236,000 babies are born with SCD in sub-Saharan Africa each year (more than 80 times as many as in the United States),1 and up to 90% will die during childhood, typically before their fifth birthday.1

In the United States, by contrast, people with SCD often live into their 40s or beyond. An important contributor to this disparity is differential access to hydroxyurea, a chemotherapeutic agent that reduces the frequency of sickle-cell crises and prolongs survival. Hydroxyurea’s clinical benefit in people with SCD was first demonstrated more than two decades ago, and it was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1998. Whereas hydroxyurea has become the standard of care for SCD in the United States, it has been vastly underutilized in sub-Saharan Africa. Concerns regarding the drug’s toxic effects and effects on vulnerability to malaria initially prevented its widespread use. Recent studies have demonstrated that hydroxyurea is safe and effective in children in sub-Saharan Africa, with treatment reducing vaso-occlusive crises, malaria incidence, and mortality.2

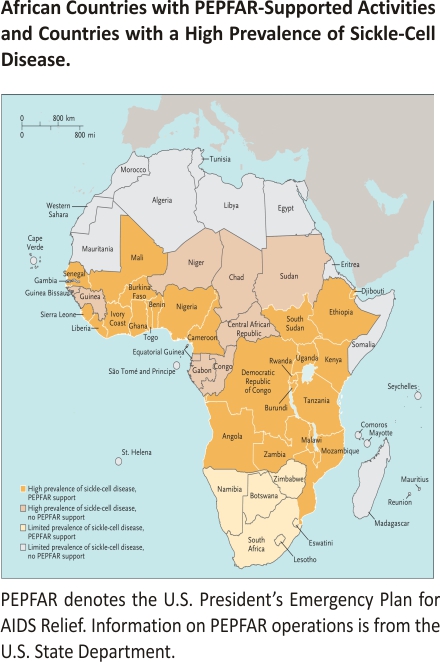

Despite these benefits, efforts to introduce hydroxyurea throughout sub-Saharan Africa have been limited owing to a dearth of clinicians in rural settings, insufficient equipment for routine blood monitoring, and relatively high costs. The Novartis Africa Sickle Cell Disease program runs 11 treatment centers in Ghana that administer hydroxyurea and serves more than 2000 patients, with plans to expand to Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania. Although admirable, this initiative represents only a small step toward ensuring access to hydroxyurea throughout the subcontinent. We believe a much larger effort is required. A multi-country program with international backing to support therapies for SCD could prevent hundreds of thousands of children from dying. One structure for implementing such a program already exists the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR).

PEPFAR is a U.S.-led interagency effort that was launched in 2003 with strong bipartisan support; its aim is to combat the HIV pandemic by supplying and negotiating the prices of antiretroviral medications and establishing basic medical and social-support services.3 The program dramatically expanded resources for capacity building by funding African medical institutions to train additional healthcare personnel and investing in infrastructure for laboratory testing throughout sub-Saharan Africa — including regions with a high incidence of SCD (see map).3

Hydroxyurea administration requires clinician oversight and periodic blood tests to support dose titration, efficacy, and safety. We believe it would be feasible to leverage PEPFAR’s framework to expand the distribution, use, and oversight of medications for SCD in resource-limited settings. These services could be grafted onto existing PEPFAR initiatives. Employing PEPFAR-trained African healthcare professionals might alleviate practical challenges in rural areas; for example, existing PEPFAR staff and sites in these regions could conduct routine clinical follow-ups for people with SCD. These efforts could relieve bottlenecks in the provision of SCD care. Although the capacity for diagnosing SCD is limited in much of sub-Saharan Africa, improving access to treatments could create incentives for national healthcare systems to improve testing and foster enthusiasm for participation in community-based screening programs.

Before a PEPFAR-based expansion of SCD treatment is implemented, a needs assessment should be conducted to identify potential barriers and facilitators. Using implementation science in the context of the PEPFAR framework to address barriers would be critical.

Taking advantage of the infrastructure used to conduct recent studies of therapies for SCD could provide another avenue for supporting drug monitoring and disease surveillance. For instance, hydroxyurea trials and the phase 3 clinical trial of voxelotor, an antipolymerization drug, involved research consortia or hospitals in Kenya, Uganda, and Egypt. These studies established the basic infrastructure and blueprints for recruiting personnel and for acquiring, using, and maintaining the equipment needed to monitor drug efficacy and toxicity.2 Combining resources would offset costs, and such coordination might require only minor additions to efforts that have already included local community leaders and governments.

A PEPFAR-based program that subsidizes or negotiates prices of medications for SCD would be another critical tool for expanding access to treatment and fostering sustainability. Using a recent analysis of a hydroxyurea formulation in sub-Saharan Africa,4 we estimated that such a program would have an initial cost of less than $100 million per year (based on a figure of $67 per person treated). Funding for this program could be added to PEPFAR’s current $7 billion annual budget.3 A daily dose of hydroxyurea in Tanzania currently costs more than U.S. $14; for a medication requiring lifelong use, this amount can be prohibitive, since the average household income is less than $30 per day. PEPFAR brokered dramatic price reductions for antiretrovirals. A similar effort to work with pharmaceutical companies to drive down the price of generic hydroxyurea formulations to $0.10 per dose, for instance, would translate into substantial savings for the program and reduced financial barriers for patients. Price-negotiation approaches used for antiretroviral drugs could be applied to therapies for SCD, and efforts to reduce prices could take advantage of PEPFAR’s existing supply-chain management and procurement systems. A PEPFAR-based program should also recognize cooperation by pharmaceutical companies by emphasizing tools such as the Access to Medicine Index, which ranks companies on the basis of their efforts to make medications affordable and accessible in 106 low- and middle-income countries. Drawing attention to such practices could foster engagement, competition, economic growth, and positive recognition, thereby encouraging companies to make more lifesaving medications available at reasonable prices.

Additional promising medications for SCD are on the horizon, and the global health community can start developing a platform to support their implementation in regions with the greatest need. In addition to the voxelotor trial, a phase 3 trial was recently completed for l-glutamine, an antioxidant that prevents sickle-cell adherence to the microvasculature, and both medications have been approved by the FDA for use in adults and some children. With an effective delivery platform in place, new therapies could be swiftly introduced in sub-Saharan Africa.

Other international agencies and organizations could provide critical support for such a program, including the World Health Organization, the United Nations Children’s Fund, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria. The Global Fund, an international organization founded in 2002, has disbursed more than U.S.$50 billion, including funds for insecticide-treated bed nets to prevent malaria transmission and medications for millions of people with tuberculosis or AIDS. Like PEPFAR, it has provided crucial infrastructure support to health systems in regions that have high rates of SCD, and its scope could grow to encompass SCD.

Support from PEPFAR, the Global Fund, other international health agencies and stakeholders, and regulatory agencies such as the FDA and the European Medicines Agency could expedite testing, certification, and implementation of new therapies and minimize the need for redundant clinical trials in low-income countries. The fundamental goal will be to generate evidence on the safety and efficacy of such medications for all children with SCD.5 Using resources established by PEPFAR and Global Fund-supported efforts to build a pipeline for delivering medications would also be an important step toward creating sustainable programs — one that could permit further expansion and development of health care systems, particularly systems to address other childhood illnesses.

Pharmaceutical companies are shepherding gene therapies and biologic products through research and development pipelines without a clear strategy for introducing these medications to the populations with the greatest need. We believe the medical community should advocate for effective, safe, and affordable therapies for SCD throughout sub-Saharan Africa. Taking advantage of existing platforms such as PEPFAR could help accomplish this important goal.

Author Affiliations

From the Malaria Research Program, Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore.

References

1. Piel FB, Patil AP, Howes RE, et al. Global epidemiology of sickle haemoglobin in neonates: a contemporary geostatistical model-based map and population estimates. Lancet 2013;381:142-151.

2. Tshilolo L, Tomlinson G, Williams TN, et al. Hydroxyurea for children with sickle cell anemia in sub-Saharan Africa. N Engl J Med 2019; 380:121-131.

3. Fauci AS, Eisinger RW. PEPFAR — 15 years and counting the lives saved. N Engl J Med 2018;378: 314-316.

4. Costa E, Tibalinda P, Sterzi E, et al. Making hydroxyurea affordable for sickle cell disease in Tanzania is essential (HASTE): how to meet major health needs at a reasonable cost. Am J Hematol 2021;96(1): E2-E5.

5. Yawn BP, Buchanan GR, Afenyi-Annan AN, et al. Management of sickle cell disease: summary of the 2014 evidence-based report by expert panel members. JAMA 2014;312:1033-1048.

Credits: Zhou AE, Travassos MA. Bringing Sickle-Cell Treatments to Children in Sub-Saharan Africa. N Engl J Med. 2022 Aug 11;387(6):488-491. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2201763. Epub 2022 Aug 6. PMID: 35929824.