Zhongxin Zhu1 , Hongliang Zhou2, Yanfei Wang3 and Xiaocong Yao1

1Department of Osteoporosis Care and Control, Xiaoshan First Affiliated Hospital of Hangzhou Normal University, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

2Department of Clinical Laboratory, Xiaoshan First Affiliated Hospital of Hangzhou Normal University, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

3Department of Medical Oncology, Xiaoshan First Affiliated Hospital of Hangzhou Normal University, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Corresponding author:

Xiaocong Yao, Department of Osteoporosis Care and Control, Xiaoshan First Affiliated Hospital of Hangzhou Normal University, Hangzhou, Zhejiang 311200, China.

Email: hzyaoxiaocong@163.com

Abstract

Objective:

To examine the associations between bone turnover markers (BTMs) and bone mineral density (BMD) in older adults aged 60–85 years.

Methods:

A total of 1124 men (mean age, 69.1 years) and 1203 women (mean age, 70.7 years) from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2002 were included in this cross-sectional analysis. Independent variables were serum bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (sBAP) and urinary N-telopeptide (uNTx), which are biomarkers of bone formation and resorption, respectively. The outcome variable was lumbar BMD. The associations of sBAP and uNTx levels with lumbar BMD was examined using multivariable linear regression models.

Results:

sBAP was negatively associated with lumbar BMD in each multivariable linear regression model, and this negative association was stable in both men and women men (men: β = −0.0028, 95% CI: −0.0046 to −0.0010; women: β = −0.0039, 95% CI: −0.0054 to −0.0023). On the other hand, uNTx was negatively associated with lumbar BMD after adjustment of relevant covariables (β = −0.0328, 95% CI: −0.0523 to −0.0133). However, in the subgroup analysis stratified by gender, this negative association remained only in older women (β = −0.0491, 95% CI: −0.0751 to −0.0231).

Conclusion:

Our study suggested that elevated sBAP and uNTX levels correlated with decreased lumbar BMD, especially in older women. This finding indicated that maintaining BTMs at low levels may be beneficial to bone health for older adults.

Keywords

bone health, bone-specific alkaline phosphatase, bone turnover markers, NHANES, N-telopeptide

Introduction

Osteoporosis has been the most common age-related bone disorder characterized by low bone mineral density (BMD) and deterioration of microarchitecture.1,2 With the ageing of the population, the number of osteoporosis patients is increasing, and osteoporosis-induced fractures are also on the rise.3 However, loss of bone occurs silently and progressively, often without symptoms until the first devastating fracture. Therefore, it is essential to understand the osteoporotic risk factors for the prevention, early diagnosis, and management of osteoporosis.

BMD measurement using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is recognized as the gold standard for the diagnosis of osteoporosis.4 However, DXA has low sensitivity, and the changes in BMD may need a long interval of more than a year.5 In the past decades, other markers for evaluating osteoporosis have attracted considerable interest. As an index reflecting the rate of bone turnover, bone turnover markers (BTMs) can be measured with blood and urine non-invasively. Hence, there has been growing interest in the potential role of BTMs in monitoring the treatment response and predicting fracture risk in daily clinical practice.6,7

Throughout life, the bone is a dynamic tissue that constantly undergoes remodelling caused by the coupling of bone formation and resorption. Nevertheless, the resorption rate exceeds the formation rate later in life among all older individuals, and prolonged bone loss leads to low BMD and eventually osteoporosis.8 Compared with BMD, which is static and represents the net gain or loss of bone mass over years to decades, BTM measurements are dynamic and reflect current bone metabolism. BTMs have long been used for research purposes to better understand the effects of bone-active medications and diseases, and BTMs are also available for clinical use. The latest guide proposed that BTMs can be used for osteoporosis fracture risk assessment, but the current results of clinical studies are not completely consistent.9–12 Thus, the purpose of this study was to examine the associations between BTMs and BMD among older adults using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES 1999– 2002).

Methods

Study design

As a cross-sectional survey on a nationally representative sample, NHANES collects data about the nutrition and health status of non-institutionalized individuals in the United States.

The NHANES program began in early 1960 as a series of surveys and became a continuous program in 1999. Each year, this survey examined about 5,000 persons who were located in counties across the country. The study was approved by the National Center of Health Statistics (NCHS) Ethics Review Board, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Participants

We used NHANES 1999–2002 data because uNTx was collected only during this period. This study was limited to older adults aged 60 years and over. After excluding 495 participants with cancer, 2327 eligible participants with all sBAP, uNTx, and lumbar BMD data were enrolled for final analysis.

Variables

sBAP was measured using the Access Ostase assay, and uNTx was assessed by using the Osteomark and Vitros ECI on-spot urine specimens.13 Lumbar BMD was determined by DXA.

For covariates, continuous variables included age, body mass index, poverty to income ratio, alkaline phosphatase, blood urea nitrogen, total cholesterol, total protein, serum uric acid, serum phosphorus, and serum calcium; categorical variables included gender, race, education, physical activities, smoking behaviour, alcohol consumption, and calcium supplementation. sBAP, uNTx, lumbar BMD and other covariate acquisition processes are available on the NHANES dataset (http://cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes).

Statistical analysis

We performed all statistical analyses by using R (http://www.R-project. org) and EmpowerStats (http://www.em powerstats.com), with statistical significance set at P < 0.05. All estimates were calculated by using sample weights following the analytical guideline edited by NCHS because the goal of NHANES is to produce data representative of the civilian noninstitutionalized US population. We constructed three multivariable linear regression models: model 1, no covariates were adjusted; model 2, age, gender, and race were adjusted; model 3, all the covariates presented in Table 1 were adjusted. Subgroup analyses were further performed. A weighted generalized additive model and a smooth curve fitting were conducted to address non-linearity.

Results

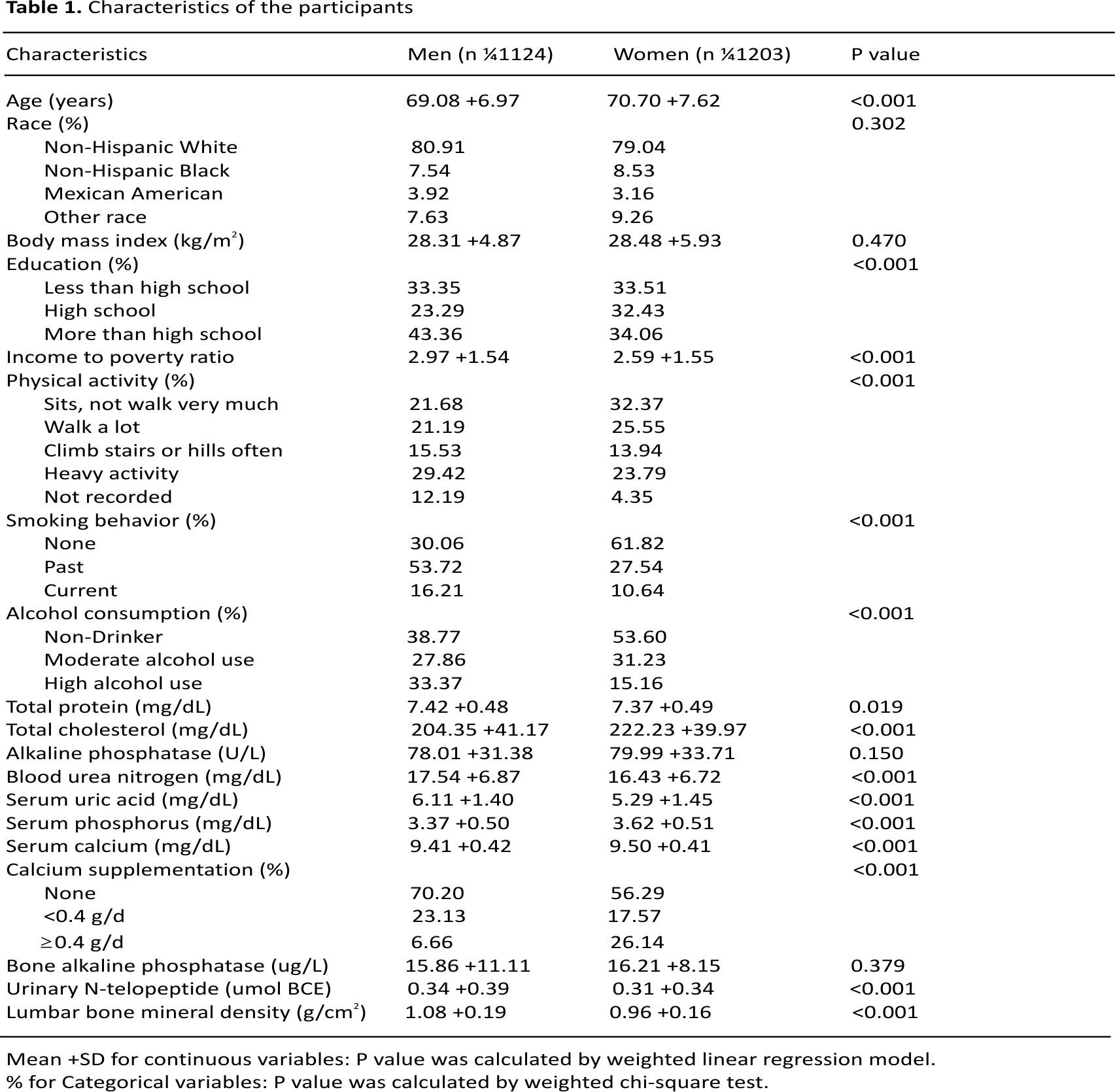

The demographic and laboratory data of the participants (1124 men and 1203 women) are presented in Table 1. Compared to men participants, women had significantly lower levels of education, physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption, income to poverty ratio, total protein, blood urea nitrogen, serum uric acid, uNTx, and lumbar BMD, had higher levels of total cholesterol, serum phosphorus, serum calcium, and calcium supplementation use.

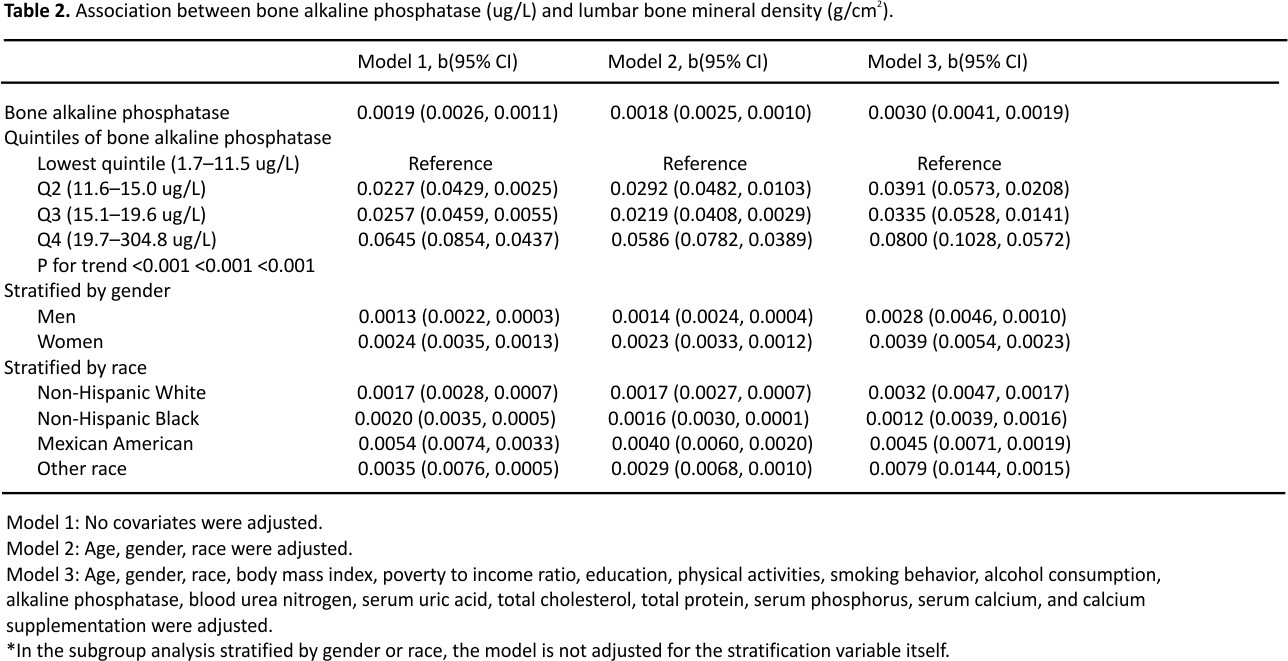

sBAP was negatively associated with lumbar BMD in each multivariable linear regression model (Table 2). The trend remained significant among different sBAP quartile groups (P < 0.001). This negative association was observed in both men (β = −0.0028, 95% CI: −0.0046 to −0.0010) and women (β = −0.0039, 95% CI: −0.0054 to −0.0023); as well as in most race groups except non-Hispanic black group.

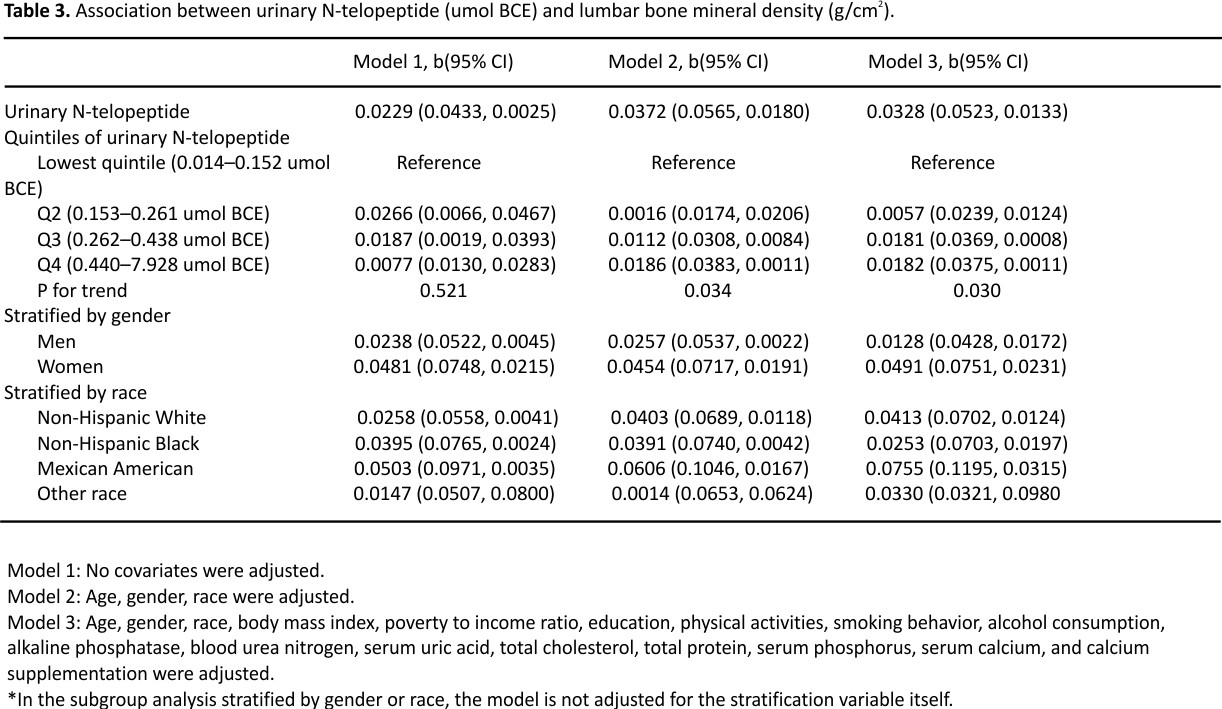

In the fully adjusted model, uNTx was negatively associated with lumbar BMD (β = −0.0328, 95% CI: −0.0523 to −0.0133), and the trend was significant among different uNTx quartile groups (Table 3). However, in the subgroup analyses stratified by gender and race, this negative association was still present only in women (β = −0.0491, 95% CI: −0.0751 to −0.0231) and non-Hispanic white, Mexican American groups.

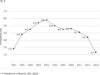

Moreover, we used a weighted generalized additive model and a smooth curve fitting to address the non-linear relationship and confirm the results (Figures 1 to 3). We further conducted sensitivity analysis by excluding 68 subjects with serum bone-specific alkaline phosphatase ≥40ug/L or urinary N-telopeptide ≥1.5 umol BCE and found that the results remained the same (Online Supplementary Figures 1 to 3).

Discussion

The overall aim of this study was to explore the associations of sBAP and uNTX levels with lumbar BMD in a nationally representative sample of US older adults. Our results suggested that elevated sBAP and uNTX levels correlated with decreased lumbar BMD, especially in older women. Although we found some non-linear associations between them, the trends were consistent with our multivariable linear regressions. This finding indicated that maintaining BTMs at a low level may be beneficial to bone health.

BTMs are important tools for drug development and clinical research studies. sBAP is an indicator of osteoporosis and an accurate and reliable marker of osteoblastic activity.14 This is supported by an NHANES study showing that sBAP is inversely associated with BMD in adults aged 20–49 years with or without diabetes.15 A cross-sectional study conducted in India showed an inverse association between sBAP and BMD of Ward’s triangle and femur neck in 95 healthy post-menopausal women.16 This conclusion was supported by other studies showing a negative association between sBAP and BMD.17–19 However, in a study involving 18 older men, the authors found no association between BAP and BMD.20 Our data showed a stable negative association between sBAP and lumbar BMD in both genders.

uNTX is collagen I derived bone resorption marker and is specific to bone due to its unique amino acid sequence, which is generated by osteoclastic activity and proteolysis.21 A longitudinal cohort study conducted in the US suggested that uNTx during the menopause transition period was strongly associated with the likelihood of bone loss at the lumbar spine over the next several years.22 Our multivariable linear regression results also suggested that elevated uNTx level was associated with low lumbar BMD in older women.

It was demonstrated that treatment-related reductions in specific BTMs are associated with a lower risk of fracture over several years.8 For example, data from the Fracture Intervention Trial suggested that greater reductions in bone turnover are associated with fewer fractures among older women with alendronate therapy.23 Elevated resorption and formation markers are associated with accelerated bone loss and increased risk of fractures among older men and women.24 Although the activities of osteoclasts and osteoblasts decrease in bone tissues of older individuals,25 may be beneficial for bone health to keep BTMs at low levels.

The present study has some notable limitations. First, the causal correlations of sBAP and uNTx with lumbar BMD were not assessed due to its cross-sectional design. A long-term observation study should be considered in future research. Second, instead of serum samples, urine samples were used to measure NTx levels in this study. NTx is the stable degradation end product, which can be measured both in serum and urine. Serum biomarkers may have better reproducibility. However, there is no scientific evidence for the superiority of serum BTMs compared with urinary BTMs.12,26,27 Third, considering the potential impacts of cancers on BTMs and BMD, we excluded patients with cancer. Therefore, the conclusion of this study is not suitable for this population.

Conclusion

Our study suggested elevated sBAP and uNTX levels correlated with decreased lumbar BMD, especially in older women. This finding indicated that maintaining BTMs at low levels may be beneficial to bone health for older adults.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the staff and the participants of the NHANES study for their valuable contributions.

Author contributions

Writing—original draft preparation: ZXZ, validation: HLZ and YFW, writing— review and editing: XCY.

Data availability

The survey data are publicly available on the internet for data users and researchers throughout the world (www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/).

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the ethics review board of the National Center for Health Statistics and written informed consents were obtained from each participant.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

1. Kanis, JA, McCloskey, EV, Johansson, H, et al. A reference standard for the description of osteoporosis. Bone 2008; 42: 467–475.

2. Jacobs, E, Senden, R, McCrum, C, et al. Effect of a semirigid thoracolumbar orthosis on gait and sagittal alignment in patients with an osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture. Clin Interv Aging 2019; 14: 671– 680.

3. Center, JR. Fracture burden: what two and a half decades of Dubbo Osteoporosis Epidemiology Study data reveal about clinical outcomes of osteoporosis. Curr Osteoporos Rep 2017; 15: 88–95.

4. Blake, GM, Fogelman, I. Role of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry in the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis. J Clin Densitom 2007; 10: 102–110.

5. Camacho, PM, Petak, SM, Binkley, N, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology clinical practise guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis— 2016: executive summary. Endocr Pract 2016; 22: 1111–1118.

6. Park, SY, Ahn, SH, Yoo, JI, et al. Position statement on the use of bone turnover markers for osteoporosis treatment. J Bone Metab 2019; 26: 213–224.

7. Nishizawa, Y, Miura, M, Ichimura, S, et al. Executive summary of the Japan Osteoporosis Society guide for the use of bone turnover markers in the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis (2018 edition). Clin Chim Acta 2019; 498: 101–107.

8. Bauer, DC. Clinical use of bone turnover markers. JAMA 2019; 322: 569–570.

9. Kanis, JA, Cooper, C, Rizzoli, R, et al. European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 2019; 30: 3–44.

10. Morris, HA, Eastell, R, Jorgensen, NR, et al. Clinical usefulness of bone turnover marker concentrations in osteoporosis. Clin Chim Acta 2017; 467: 34–41.

11. Tian, A, Ma, J, Feng, K, et al. Reference markers of bone turnover for the prediction of fracture: a meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res 2019; 14: 68.

12. Vilaca, T, Gossiel, F, Eastell, R. Bone turnover markers: use in fracture prediction. J Clin Densitom 2017; 20: 346–352.

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm

14. Leung, KS, Fung, KP, Sher, AH, et al. Plasma bone-specific alkaline phosphatase as an indicator of osteoblastic activity. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1993; 75: 288–292.

15. Chen, H, Li, J, Wang, Q. Associations between bone-alkaline phosphatase and bone mineral density in adults with and without diabetes. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018; 97: e0432.

16. Kumar, A, Devi, SG, Mittal, S, et al. A hospital-based study of biochemical markers of bone turnovers & bone mineral density in north Indian women. Indian J Med Res 2013; 137: 48–56.

17. Bruyere, O, Collette, J, Delmas, P, et al. Interest of biochemical markers of bone turnover for long-term prediction of new vertebral fracture in postmenopausal osteoporotic women. Maturitas 2003;

44: 259– 265.

18. Ross, PD, Knowlton, W. Rapid bone loss is associated with increased levels of biochemical markers. J Bone Miner Res 1998; 13: 297–302.

19. Gurban, CV, Balaş, MO, Vlad, MM, et al. Bone turnover markers in postmenopausal osteoporosis and their correlation with bone mineral density and menopause duration. Rom J Morphol Embryol 2019; 60: 1127–1135.

20. Lumachi, F, Orlando, R, Fallo, F, et al. Relationship between bone formation markers bone alkaline phosphatase, osteocalcin and amino-terminal propeptide of type I collagen and bone mineral density in elderly men. Preliminary results. In Vivo 2012; 26: 1041–1044.

21. Ganesan, GR, Vijayaraghavan, PV. Urinary N-telopeptide: the new diagnostic test for osteoporosis. Surgery J (N Y) 2019; 5: e1–e4.

22. Shieh, A, Greendale, GA, Cauley, JA, et al. Urinary N-telopeptide as a predictor of the onset of menopause-related bone loss in pre-and perimenopausal women. JBMR Plus 2019; 3: e10116.

23. Bauer, DC, Black, DM, Garnero, P, et al. Change in bone turnover and hip, non-spine, and vertebral fracture in alendronate-treated women: the Fracture Intervention Trial. J Bone Miner Res 2004; 19: 1250– 1258.

24. Johansson, H, Odén, A, Kanis, JA, et al. A meta-analysis of reference markers of bone turnover for the prediction of fracture. Calcif Tissue Int 2014; 94: 560–567.

25. Shen, L, Zhou, S, Glowacki, J. Effects of age and gender on WNT gene expression in human bone marrow stromal cells. J Cell Biochem 2009; 106: 337–343.

26. Baxter, I, Rogers, A, Eastell, R, et al. Evaluation of urinary N-telopeptide of type I collagen measurements in the management of osteoporosis in clinical practice. Osteoporos Int 2013; 24: 941–947.

27. Löfman, O, Magnusson, P, Toss, G, et al. Common biochemical markers of bone turnover predict future bone loss: a 5-year follow-up study. Clin Chim Acta 2005; 356: 67–75.

CREDITS:

Zhu Z, Zhou H, Wang Y, Yao X. Associations between bone turnover markers and bone mineral density in older adults. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2021 Jan-Apr;29(1):23094990209876 53. doi: 10.1177/2309499020987653. PMID: 33480325.