Authors: Altomari, Nataliaa; 1 | Bruno, Francescob; 1 | Laganà, Valentinab | Smirne, Nicolettab | Colao, Rosannab | Curcio, Sabrinab | Di Lorenzo, Raffaeleb | Frangipane, Francescab | Maletta, Raffaeleb | Puccio, Gianfrancob | Bruni, Amalia Ceciliab; *

Affiliations: [a] Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, University of Calabria, Rende (CS), Italy | [b] Regional Neurogenetic Centre (CRN), Department of Primary Care, ASP Catanzaro, Lamezia Terme (CZ), Italy

Correspondence: [*] Correspondence to: Amalia Cecilia Bruni, Regional Neurogenetic Centre (CRN), Azienda Sanitaria Provinciale di Catanzaro, Viale A. Perugini, 88046 Lamezia Terme (CZ), Italy.

E-mail: amaliaceciliabruni@gmail.com.

Abstract

Background:

Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) have a large impact on the quality of life of patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Few studies have compared BPSD between early-onset (EOAD) and late-onset (LOAD) patients, finding conflicting results.

Objective:

The aims of this study were to:

1) characterize the presence, overall prevalence, and time of occurrence of BPSD in EOAD versus LOAD;

2) estimate the prevalence over time and severity of each BPSD in EOAD versus LOAD in three stages: pre-T0 (before the onset of the disease), T0 (from onset to 5 years), and T1 (from 5 years onwards);

3) track the manifestation of BPSD sub-syndromes (i.e., hyperactivity, psychosis, affective, and apathy) in EOAD versus LOAD at T0 and T1.

Methods:

The sample includes 1,538 LOAD and 387 EOAD diagnosed from 1996 to 2018. Comprehensive assessment batteries, including the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI), were administered at the first medical assessment and at different follow-up periods.

Results:

The overall prevalence for most BPSD was significantly higher in EOAD compared to LOAD whereas most BPSD appeared significantly later in EOAD patients. Between the two groups, from pre-T0 to T1 we recorded a different pattern of BPSD prevalence over time as well as for BPSD sub-syndromes at T0 and T1. Results on the severity of BPSD did not show significant differences.

Conclusion:

EOAD and LOAD represent two different forms of a single entity not only from a neuropathological, cognitive, and functional level but also from a psychiatric point of view.

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most widespread neurodegenerative disorder affecting more than 24 million people worldwide 1–3. Although it is considered mainly characterized by progressive memory loss and other cognitive function deficits 3,4, an ever-increasing number of studies recognize neuropsychiatric or behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) as core features of AD 5–7.

BPSD is a wide range of non-cognitive symptoms that can be classified into four different sub-syndromes: hyperactivity (agitation, disinhibition, irritability, aberrant motor behavior, and euphoria), psychosis (sleep and nighttime behavior disorders, delusion, hallucination), affective (depression and anxiety), and apathy (apathy and eating disorders) 5,8.

Usually, all twelve BPSD as well as BPSD sub-syndromes are assessed by using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) both in clinical practice and research contexts 9.

Several studies have reported that BPSD may have harmful consequences by reducing the quality of life of AD patients and caregivers 10–12 and increasing caregivers’ distress and burden 13–15. In addition, BPSD represents an important cause of early institutionalization 16–18 leading to considerable healthcare costs 19–20.

Although most AD patients display several BPSD 7,21 their occurrence, prevalence, and severity changes depend on the type of sample and setting considered 22. A growing body of evidence indicates that there are differences in the manifestation of BPSD between early-onset (EOAD, onset <65 years old) and late-onset (LOAD, onset >65 years) AD patients 23–29.

However, conflicting results have been achieved in these studies when comparing the two populations with respect to the prevalence of symptoms both at first medical assessment and when making a longitudinal comparison. Some authors found that the prevalence of most BPSD was lower 3–25, higher 26, or equal 27 in EOAD compared to LOAD.

The only two longitudinal studies 28,29 showed totally different figures of BPSD in EOAD compared to LOAD over two years and four years of assessment, respectively.

The above-reported contrasting results were probably due to methodological differences and small sample sizes particularly for EOAD patients 23–29.

As far as we know, a comparison has never been made between EOAD and LOAD patients regarding the time of occurrence, prevalence, and severity of BPSD from before the onset to the whole course of the disease. In addition, no studies compared the manifestation of BPSD sub-syndromes (i.e., hyperactivity, psychosis, affective, and apathy) between EOAD and LOAD patients both before the onset and at different stages of the disease.

Thus, the aim of the current study was threefold. First, to better characterize the occurrence and overall prevalence of BPSD in a large cohort of EOAD versus LOAD patients. Second, to estimate prevalence over time, time of occurrence, and severity of each BPSD in EOAD versus LOAD patients by arbitrarily analyzing three stages on the basis of mean duration of illness: pre-T0 (before the onset of the disease), T0 or Manifested Disease (from onset to 5 years), and T1 or Advanced (from 5 years onwards). Third, to compare the overall prevalence of BPSD sub-syndromes (i.e., hyperactivity, psychosis, affective, and apathy) in EOAD versus LOAD patients at T0 and T1.

METHODS

Subjects

The dataset includes 1,925 patients (1,292 women and 633 men) diagnosed with AD and followed at the Regional Neurogenetic Centre (ASP CZ) from 1996 to 2018. The diagnosis was performed according to NINCDS-ADRDA criteria 30 and National Institute on Aging and Alzheimer’s Association Workgroup 31.

The mean age of the whole sample was 71.58±9 years (57.7±4.9 years for EOAD and 75±5.7 years for LOAD patients). The mean follow-up was 4 years, assessment was at every six months. The mean duration of illness was about 9-years. Most of the patients were from southern Italy. Data were retrospectively extracted from the respective medical records on the basis of completeness of clinical data. Inclusion criteria were: 1) Diagnosis of probable AD according to the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria; 2) Availability of a reliable caregiver; 3) Completeness of clinical data. Exclusion criteria were: 1) Patients with a past history of psychiatric illness and/or any neurological illness that could interfere with neuropsychological tests; 3) Unavailability of a reliable caregiver; 4) Incompleteness of clinical data; 5) Patients free from pharmacologic treatments for BPSD; 6) Known or suspected history of alcoholism or drug abuse.

The work was done according to the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 and approved by the Ethical Committee of Calabria Region (Catanzaro, Italy).

Measures

All patients regularly performed at the first assessment and every six months the following examinations:

• Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) 32,33;

• Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR) 34, 35;

• Clinical Insight Rating Scale (CIRS) 36;

• Activities of Daily Living (ADL) 37 and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) 38;

• Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) to identify both individual BPSD 39,40 and BPSD sub-syndromes 5,8;

• Checklist encompassing the same BPSD of NPI referred to pre-T0 and extrapolated from the patient’s history collected in the medical records 41.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed with SPSS statistical software 21 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). To analyze the occurrence and prevalence of BPSD, descriptive statistics, frequencies, contingency, and coefficient tests (cross tabs) were evaluated. For the analysis of dichotomous variables between two groups, a chi-square cross tabs test was performed. Statistical significance was given by a p < 0.05.

Frequencies were used to calculate the overall prevalence for each BPSD at a given time. The differences between EOAD and LOAD were analyzed with the chi-square test. To calculate the occurrence and prevalence over time, three periods in which symptoms appeared for the first time in our sample were analyzed. The time of occurrence of each BPSD was calculated as a mean of onset among EOAD and LOAD patients. To measure the general trend of the sub-syndromes, four clusters were created accordingly to Zhao et al. 5 and Aalten et al. 8, and their prevalence was calculated through frequency analysis. Finally, to analyze BPSD severity we compared 1) NPI total score, 2) each individual BPSD, and 3) BPSD sub-syndromes at T0 and T1, between EOAD and LOAD by one-way ANOVA.

RESULTS

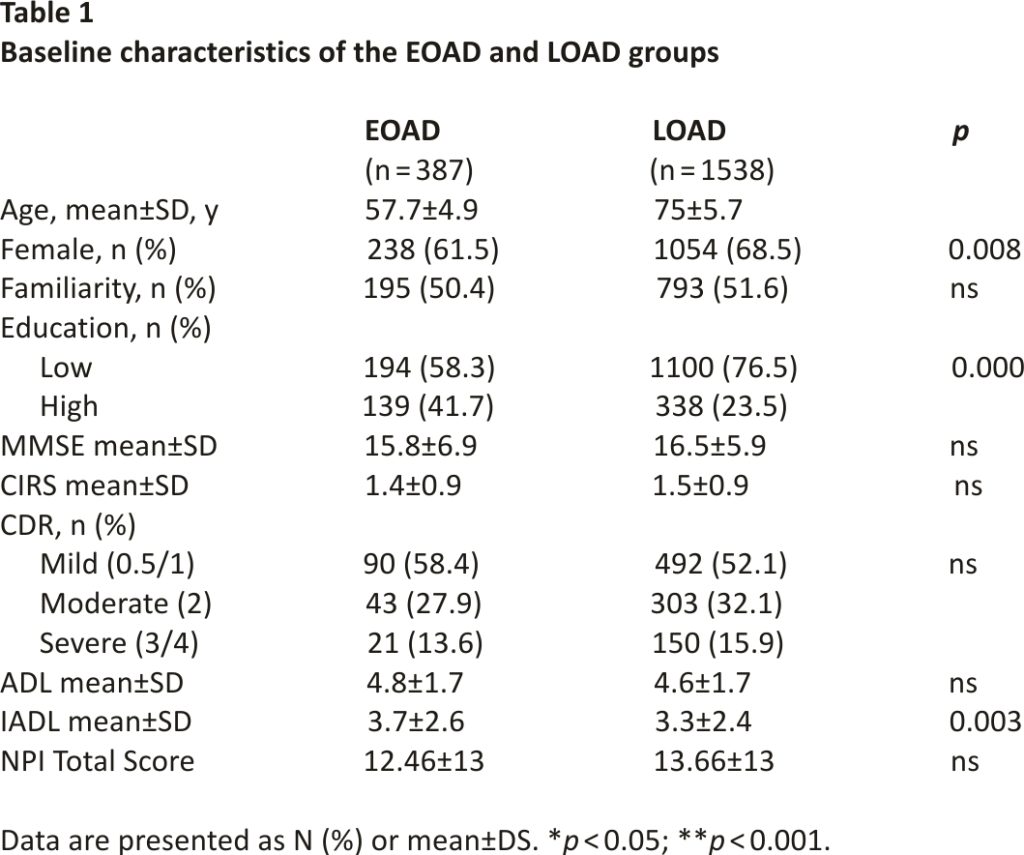

A total of 1,925 patients were included (387 EOAD and 1,538 LOAD). Table 1 shows demographic data for each group. The percentage of females was greater in LOAD compared to the EOAD group (p = 0.008), the EOAD group was higher educated (p = 0.000) and scored higher in the IADL (p = 0.003). No significant differences different in terms of family history of dementia, MMSE, CIRS, CDR, NPI, and ADL scores were found between the two groups.

The overall prevalence of BPSD

The pattern of the overall prevalence of BPSD in the whole sample is presented in Supplementary Figure 1. Considering the whole sample, 90.8%of the patients manifested at least one BPSD. More than two-thirds of patients showed Apathy (57.4%), followed by Irritability (50.5%), Agitation (42.3%), Depression (38.8%), Sleep and Nighttime Behavior Disorders (35.6%), Hallucinations (27.5%), Anxiety (26.8%), Disinhibition (26.3%), Delusions (24.8%), Eating Disorders (13.6%), Aberrant Motor Behavior (10.6%), and Euphoria (2.3%).

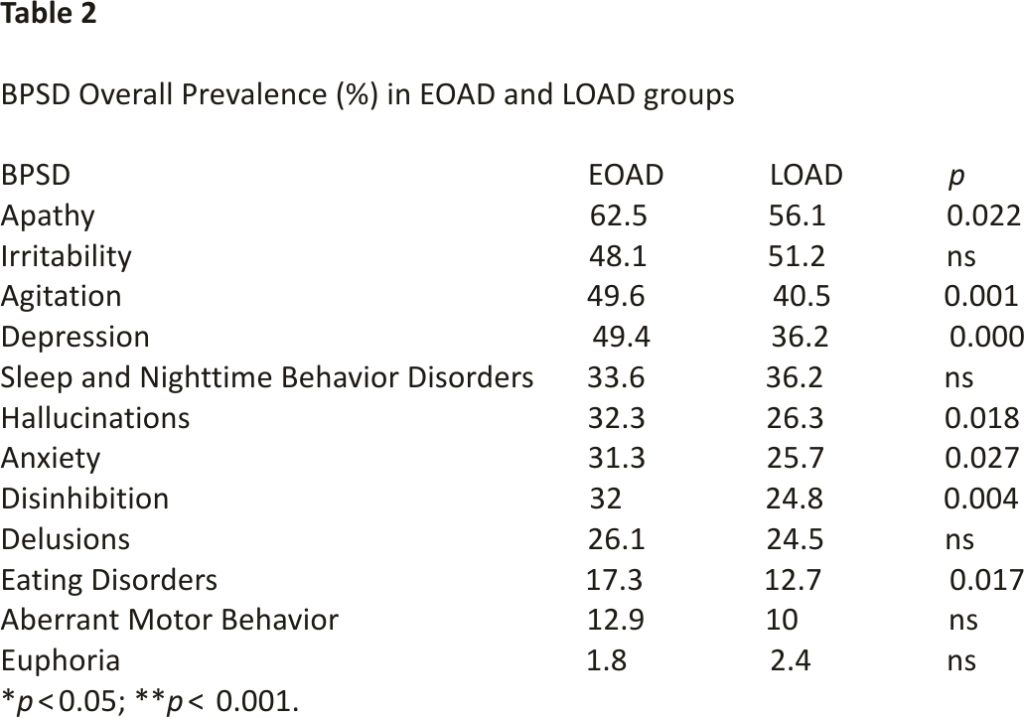

The pattern of the overall prevalence of BPSD between the two groups is presented in Table 2. The prevalence was significantly higher in EOAD compared to LOAD patients for Apathy (p = 0.022), Agitation (p = 0.001), Depression (49.4 versus 36.25, p = 0.000), Hallucination (p = 0.018), Anxiety (p = 0.027), Disinhibition (p = 0.004), and Eating Disorders (p = 0.017).

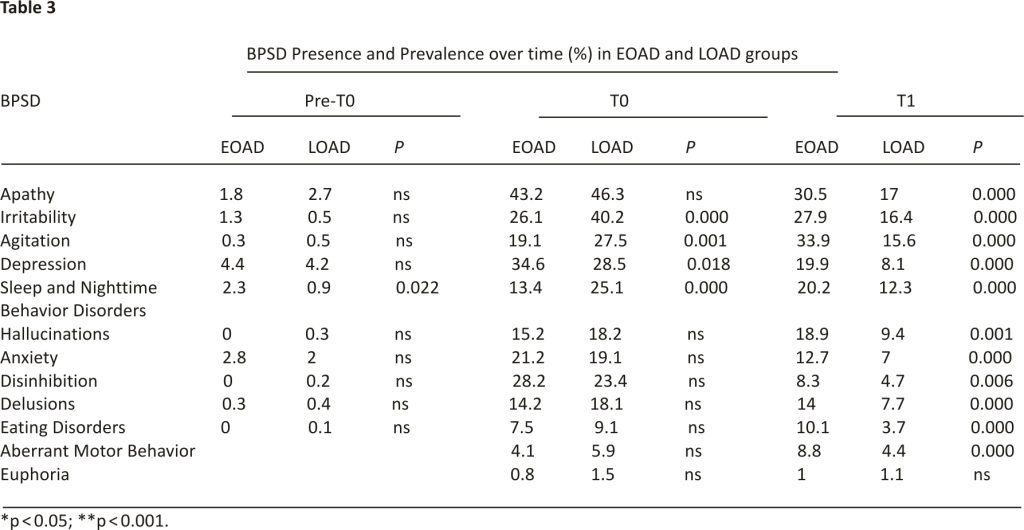

Occurrence and prevalence over time of BPSD

The occurrence and prevalence over time of each BPSD in the whole sample are presented in Supplementary Figure 2. At pre-T0 (Supplementary Figure 2a), Depression, Anxiety, Apathy, and Sleep and Nighttime Behavior Disorders were the symptoms most represented whereas at T0 (Supplementary Figure 2b) and T1 (Supplementary Figure 2c) all BPSD were strongly shown except Euphoria. The occurrence and prevalence over time of each BPSD between EOAD and LOAD are presented in Table 3. At pre-T0, the prevalence of Sleep and Nighttime Behavior Disorders was higher in EOAD (p = 0.022). At T0, Irritability (p = 0.000), Agitation (p = 0.001), and Sleep and Nighttime Behavior Disorders (p = 0.000) were more frequent in LOAD, whereas Depression was more prevalent in EOAD (p = 0.018). At T1 Apathy (p = 0.000), Irritability (p = 0.000), Agitation (p = 0.000), Depression (p = 0.000), Sleep and Nighttime Behavior Disorders (p = 0.000), Hallucinations (p = 0.001), Anxiety (p = 0.000), Disinhibition (p = 0.006), Delusions (p = 0.000), Eating Disorders (p = 0.000), Aberrant Motor Behavior (p = 0.000), were more prevalent in EOAD compared to LOAD patients.

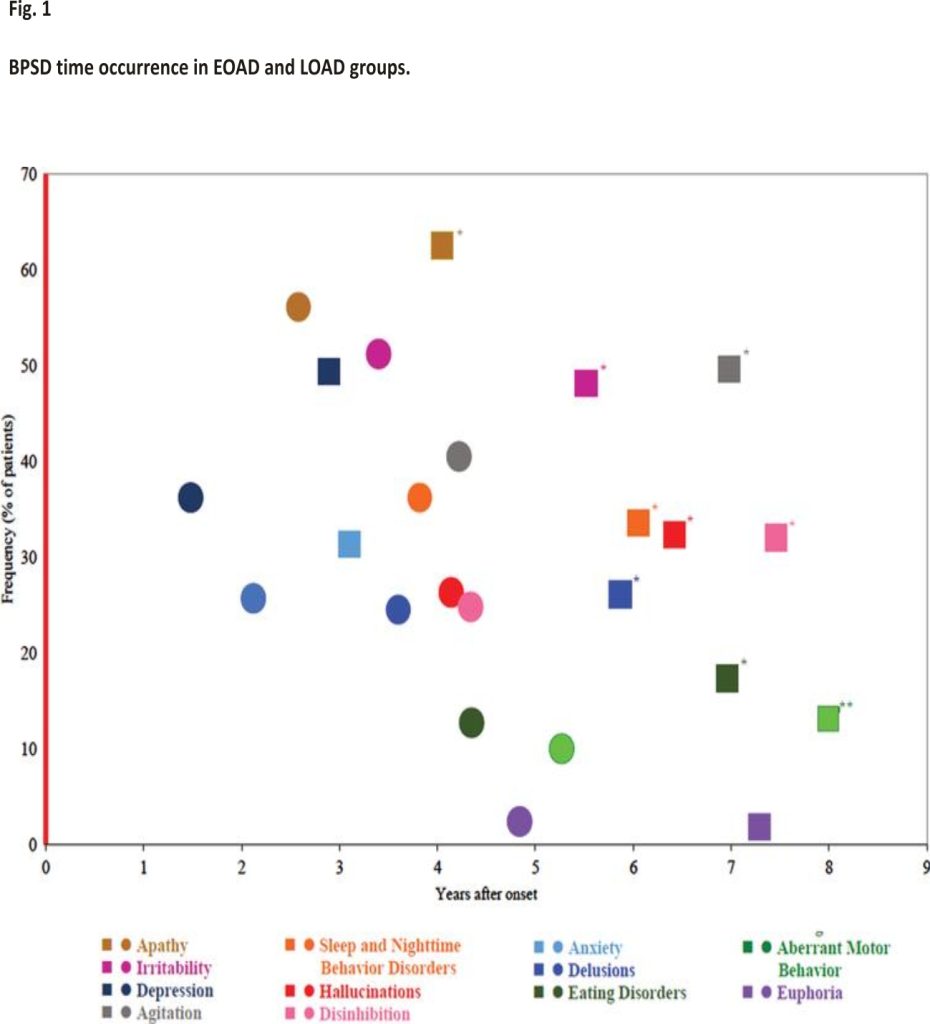

Time of occurrence of BPSD

The time of occurrence is presented in Fig. 1. Most BPSD were distributed between the fourth and fifth year after the onset of the disease in all groups. However, Apathy (p = 0.000), Irritability (p = 0.000), Agitation (p = 0.001), Sleep and Nighttime Behavior Disorders (p = 0.04), Hallucinations (p = 0.001), Disinhibition (p = 0.002), Delusions (p = 0.000), Eating Disorders (p = 0.000), and Aberrant Motor Behavior (p = 0.04) appeared significantly later in EOAD compared to LOAD patients.

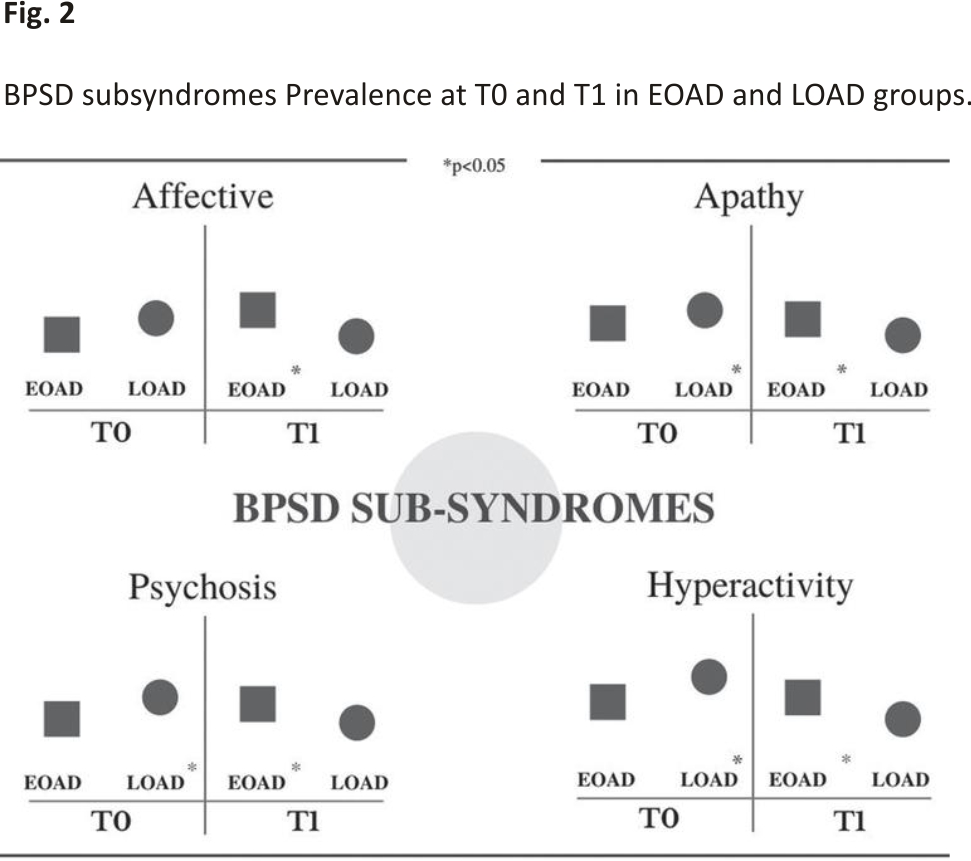

BPSD sub-syndromes prevalence

The prevalence of BPSD sub-syndromes is presented in Fig. 2. At T0, Apathy (p = 0.000), Psychosis (p = 0.000), and Hyperactivity (p = 0.000) were more prevalent in the LOAD group. At T1 all the four sub-syndromes, namely, Affective (p = 0.000), Apathy (p = 0.000), Psychosis (p = 0.013), and Hyperactivity (p = 0.000) were more prevalent in the EOAD group.

Severity of BPSD

Finally, severity was investigated for the Total NPI score, for each individual BPSD and for the BPSD sub-syndromes at T0 and T1. Results did not show significant differences (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The main aim of this study was to characterize the occurrence, time of occurrence, prevalence, and severity of BPSD and the prevalence of BPSD sub-syndromes in a large cohort of EOAD versus LOAD. Patients were observed at three stages: pre-T0 (before the onset of the disease), T0 or Manifested Disease (from onset to 5 years), and T1 or Advanced (from 5 years onwards).

Overall prevalence and prevalence over time of BPSD in the whole sample

The analyses of the overall prevalence of each BPSD in the whole sample showed that apathy was the most frequent symptom (Supplementary Material), in line with previously published data 5,42,43. This finding was very important since there is often an overlap between apathy and depression in dementia 44,45. Because depression and apathy have different neurobiological basis it is essential to identify them as two distinct BPSDs in order to guide treatment decisions 46. In addition, our results showed that euphoria was the less common symptom according to a recent meta-analysis that included 64 studies carried out between 1964 and 2014 5. Considering the prevalence over time we found that depression, anxiety, and apathy occur before the onset of AD (see the Supplementary Material) accordingly to previous data for AD 47,48 and mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Thus anxiety, depression, and apathy could represent a wake-up call to which clinicians should pay attention for the early detection of AD before the cognitive decline as already suggested by Ma et al. 49. This paper outlines that these three BPSD when present at the same time seems to predict both cognitive decline and progression from MCI to AD 49. In addition, it has been suggested that depression could represent a risk factor for developing dementia strengthening the importance to implement preventive strategies targeting especially this latter BPSD 50.

The overall prevalence of BPSD in EOAD versus LOAD patients

Although BPSD is common in both EOAD and LOAD patients, their prevalence and frequency vary across the few studies carried out so far. Our findings are in keeping with those that found a higher BPSD prevalence in EOAD compared to LOAD patients 26, 29. We found in particular that apathy, agitation, depression, hallucinations, anxiety, disinhibition, and eating disorders were significantly higher in EOAD patients (Table 2). The cause for increased BPSD in EOAD is likely multifactorial and includes both social and biological factors. Receiving a diagnosis of AD is probably more emotionally difficult for EOAD than LOAD patients due to their younger age, and more responsibilities within their families such as taking care of children and holding down a job 29. In addition, the pathophysiology of AD spreads in a more rapid and aggressive manner in EOAD compared to LOAD 51 determining a worse prognosis 52.

Prevalence over time of BPSD in EOAD versus LOAD patients

Comparing BPSD prevalence over time in the two groups we showed that in the preT0 phase the prevalence of Sleep and Nighttime Behavior Disorders was higher in EOAD compared to LOAD patients. However, at T0 these symptoms were higher in LOAD associated also with Irritability, Agitation, and Depression. Successively, at the T1 phase, all BPSD were more represented in EOAD patients. These results were particularly relevant demonstrating that EOAD is more rapid and aggressive than LOAD not only at a neuropathological 51,53,54, cognitive 52,55, and functional 52 level but also at a psychiatric dimension.

Time of occurrence of BPSD in EOAD versus LOAD patients

Most BPSD occurred between the fourth and fifth year of the disease in both groups. However, Apathy, Irritability, Agitation, Sleep, and Nighttime Behavior Disorders, Hallucinations, Disinhibition, Delusions, Eating Disorders, and Aberrant Motor Behavior emerged significantly early in LOAD compared to EOAD patients. Anxiety, Depression, and Euphoria presented with the same trend of occurrence without significant difference. This distribution can reflect the fact that a high proportion of AD patients receive a delayed diagnosis as already pointed out 56 probably when cognitive symptoms become disabling and/or BPSD destroys the family context.

However, as we already mentioned, some BPSD were present before the onset of AD in line with the literature that conceptualized mild behavioral impairment (MBI) as a transitional state between normal aging and dementia present even before cognitive symptoms appear 57,58. Thus, it is of primary importance to instruct general practitioners to consider BPSD as a possible precursor of dementia and to promote awareness campaigns in the general population to reach an early diagnosis and, therefore, provide care as soon as possible.

Prevalence of BPSD sub-syndromes in EOAD versus LOAD patients

This study represents also the first attempt to compare and characterize the prevalence of BPSD sub-syndromes in EOAD versus LOAD patients. In agreement with the previous studies on BPSD subsyndromes, that considered AD patients without making a distinction between EOAD and LOAD, all 4 sub-syndromes were manifested by AD patients 5,8. Interestingly, we found a different pattern of prevalence of BPSD sub-syndromes between EOAD and LOAD considering two different time points, namely, T0 and T1. At T0 the prevalence of the subsyndromes Apathy, Psychosis, and Hyperactivity was higher in LOAD patients whereas we found no difference in the prevalence of Affective sub-syndrome between the two groups. Furthermore, at T1 the prevalence of all sub-syndromes was higher in EOAD compared to LOAD patients. This pattern of BPSD sub-syndromes strengthens the need to consider EOAD and LOAD as two different forms of a single entity 58 also from a psychiatric point of view.

BPSD severity in EOAD versus LOAD patients

The overall NPI total score was not significantly different between the two groups according to previous studies 26,27 and also the severity of each BPSD and BPSD sub-syndromes, at T0 and T1, was similar. Overall, these findings demonstrated that it is important to give equal attention to BPSD throughout the whole course of the illness in order to guide treatment choices and strategies for both EOAD and LOAD patients.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study has some criticisms. These include the different distributions of gender, level of education, and IADL score between the two groups. However, it is well known that AD is a higher prevalence in women than men, particularly at age of 70 years 60. This might have unbalanced our sample. Concerning the different levels of education, it has been shown that EOAD patients are typically more instructed compared to LOAD patients 52 probably due to the improvement in the education system. As mentioned above, the analyses performed showed that EOAD displays more apathy than LOAD patients. Accordingly, to the previous literature, the lower IADL score of EOAD could be explained by persistent apathy that predicts a more rapid instrumental functional decline 61. In fact, the two groups were comparable for MMSE, CDR, CIRS, ADL, and NPI total scores strengthening the validity of our analyses.

A strong point of this study was the sample size. Our research was performed on a very large number of patients, unlike the previous studies. Second, patients were followed for a long time and their data was collected with the same methodology and the same research team since 1996. Finally, as far as we know, this study represents the first attempt to compare the prevalence of BPSD sub-syndromes between EOAD and LOAD patients.

Conclusion

In conclusion, EOAD and LOAD represent two different forms of a single entity not only at a neuropathological, cognitive, and functional level but also from a psychiatric point of view. Indeed, BPSD manifests differently in occurrence, time of occurrence, overall prevalence, and prevalence over time between EOAD and LOAD patients throughout the whole course of the illness. Along the same line also the prevalence of BPSD sub-syndromes follows a different pattern of manifestation over time. Our findings reinforce the clinical importance of not considering AD only as a “cognitive” disease emphasizing the urgency of characterizing the BPSD pattern of each patient to guide treatment choices and strategies. Interestingly, some signs of behavioral changes, such as apathy, depression, and anxiety, appear in both EAOD and LOAD patients before the onset of AD. The identification of these “wake-up call” signs of AD can be important and significant for the early detection of the disease. The different patterns of BPSD that we observed between EOAD and LOAD patients can be related to several genetic risk factors, brain pathophysiological changes, gender differences, and drug usage. Indeed, further studies are needed to correlate genetic risk factors with the manifestation of BPSD, as well as, to analyze the different patterns of BPSD and brain functional changes across the course of the disease in EOAD and LOAD, taking into account gender differences and drugs.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Authors’ disclosures are available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/21-5061r1).

REFERENCES

[1] García-Blanco A, Baquero M, Vento M, Gil E, Bataller L, Cháfer-Pericás C (2017) Potential oxidative stress biomarkers of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Sci 373, 295–302.

[2] Li J, Cesari M., Liu F, Dong B, Vellas B (2017) Effects of diabetes mellitus on cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review. Can J Diabetes 41, 114–119.

[3] Zheng W, Su Z, Liu X, Zhang H, Han Y, Song H, Lu J, Li K, Wang Z (2018) Modulation of functional activity and connectivity by acupuncture in patients with Alzheimer’s disease as measured by resting-state fMRI. PLoS One 13, e0196933.

[4] Pievani M, de Haan W, Wu T, Seeley WW, Frisoni GB (2011) Functional network disruption in the degenerative dementias. Lancet Neurol 10, 829– 843.

[5] Zhao QF, Tan L, Wang HF, Jiang T, Tan MS, Tan L, Xu W, Li JQ, Wang J, Lai TJ, Yu JT (2016) The prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 190, 264–271.

[6] Petrovic M, Hurt C, Collins D, Burns A, Camus V, Liperoti R, Marriott A, Nobili F, Robert P, Tsolaki M, Vellas B (2007) Clustering of behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia (BPSD): A European Alzheimer’s disease consortium (EADC) study. Acta Clin Belg 62, 426–432.

[7] Lyketsos CG, Carrillo MC, Ryan JM, Khachaturian AS, Trzepacz P, Amatniek J, Cedarbaum J, Brashear R, Miller DS (2011) Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement 7, 532–539.

[8] Aalten P, Verhey FR, Boziki M, Brugnolo A, Bullock R, Byrne EJ, Camus V, Caputo M, Collins D, De Deyn PP, Elina K (2008) Consistency of neuropsychiatric syndromes across dementias: Results from the European Alzheimer Disease Consortium. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 25, 1–8.

[9] Cummings J (2020) The neuropsychiatric inventory: Development and applications. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 33, 73–84.

[10] Shin IS, Carter M, Masterman D, Fairbanks L, Cummings JL (2005) Neuropsychiatric symptoms and quality of life in Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 13, 469–47 4.

[11] Hongisto K, Hallikainen I, Selander T, Törmälehto S, Väätäinen S, Martikainen J, Välimäki T, Hartikainen S, Suhonen J, Koivisto AM (2018) Quality of Life in relation to neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: 5-year prospective ALSOVA cohort study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 33, 47–57.

[12] Tatsumi H, Nakaaki S, Torii K, Shinagawa Y, Watanabe N, Murata Y, Sato J, Mimura M, Furukawa TA (2009) Neuropsychiatric symptoms predict change in the quality of life of Alzheimer disease patients: A two-year follow-up study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 63, 374–384.

[13] Chen CT, Chang CC, Chang WN, Tsai NW, Huang CC, Chang YT, Wang HC, Kung CT, Su YJ, Lin WC, Cheng BC, Lu CH (2017) Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: Associations with caregiver burden and treatment outcomes. QJM 110, 565–570.

[14] Hallikainen I, Koivisto AM, Välimäki T (2018) The influence of the individual neuropsychiatric symptoms of people with Alzheimer’s disease on family caregiver distress—a longitudinal ALSOVA study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 33, 1207–1212.

[15] Isik AT, Soysal P, Solmi M, Veronese N (2019) Bidirectional relationship between caregiver burden and neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: A narrative review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 34, 1326–1334.

[16] Brodaty H, Connors MH, Xu J, Woodward M, Ames D, PRIME Study Group (2014) Predictors of institutionalization in dementia: A three-year longitudinal study. J Alzheimers Dis 40, 221–226.

[17] Chan DC, Kasper JD, Black BS, Rabins PV (2003) Presence of behavioral and psychological symptoms predicts nursing home placement in community-dwelling elders with cognitive impairment in univariate but not multivariate analysis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 58, M548–M554.

[18] Jones RW, Romeo R, Trigg R, Knapp M, Sato A, King D, Niecko T, Lacey L, Group DI (2015) Dependence in Alzheimer’s disease and service use costs, quality of life, and caregiver burden: The DADE study. Alzheimer’s Dement 11, 280–290.

[19] Maust DT, Kales HC, McCammon RJ, Blow FC, Leggett A, Langa KM (2017) Distress associated with dementia-related psychosis and agitation in relation to healthcare utilization and costs. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 25, 1074–1082.

[20] Eikelboom WS, Singleton E, Van Den Berg E, Coesmans M, Raso FM, Van Bruchem RL, Goudzwaard JA, De Jong FJ, Koopmanschap M, Den Heijer T, Driesen JJ, Papma JM (2019) Early recognition and treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms to improve quality of life in early Alzheimer’s disease: Protocol of the BEAT-IT study. Alzheimer’s Res Ther 11, 48.

[21] Geda YE, Schneider LS, Gitlin LN, Miller DS, Smith GS, Bell J, Evans J, Lee M, Porsteinsson A, Lanctot KL, Rosenberg PB, Lyketsos CG (2013) Neuropsychiatric Syndromes Professional Interest Area of ISTAART (2013) Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: Past progress and anticipation of the future. Alzheimer’s Dement 9, 602–608.

[22] Cerejeira J, Lagarto L, Mukaetova-Ladinska E (2012) Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Front Neurol 3,73.

[23] Spalletta G, Luca V, Padovani A., Rozzini L, Perri R, Bruni A, Canonico V, Trequattrini A, Bellelli G, Pettenati C, Pazzelli F, Caltagirone C, Orfei M (2013) Early onset versus late onset in Alzheimer’s disease: What is the reliable cut-off? Adv Alzheimers Dis 2, 40–47.

[24] Toyota Y, Ikeda M, Shinagawa S, Matsumoto T, Matsumoto N, Hokoishi K, Fukuhara R, Ishikawa T, Mori T, Adachi H, Komori K, Tanabe H (2007) Comparison of behavioral and psychological symptoms in early-onset and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 22, 896–901.

[25] Mushtaq R, Pinto C, Tarfarosh SF, Hussain A, Shoib S, Shah T, Shah S, Manzoor M, Bhat M, Arif T (2016) A comparison of the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) in early-onset and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease-a study from South East Asia (Kashmir, India). Cureus 8, e625.

[26] Baillon S, Gasper A, Wilson-Morkeh F, Pritchard M, Jesu A, Velayudhan L (2019) Prevalence and severity of neuropsychiatric symptoms in early-versus late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 34, 433–438.

[27] Ferreira MDC, Abreu MJ, Machado C, Santos B, Machado Á, Costa AS (2018) Neuropsychiatric profile in early versus late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 33, 93–99.

[28] Van Vliet D, De Vugt ME, Aalten P, Bakker C, Pijnenburg YA, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Koopmans RT, Verhey FR (2012) Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in young-onset compared to late-onset Alzheimer’s disease– part 1: Findings of the two-year longitudinal NeedYD-study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 34, 319–327.

[29] Gumus M, Multani N, Mack ML, Tartaglia MC (2021) Progression of neuropsychiatric symptoms in young-onset versus late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Geroscience 43, 213–223.

[30] McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM (1984) Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group* under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 34, 939–944.

[31] McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR Jr, Kawas CH, Klunk WE, Koroshetz WJ, Manly JJ, Mayeux R, Mohs RC, Phelps CH (2011) The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement 7, 263–269.

[32] Folstein M, Folstein SE, McHugh P (1975) Mini-Mental State: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12, 189–198.

[33] Magni E, Binetti G, Bianchetti A, Rozzini R, Trabucchi M (1996) Mini-Mental State Examination: A normative study in Italian elderly population. Eur J Neurol 3, 198–202.

[34] Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger W, Coben LA, Martin RL (1982) A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry 140, 566–572.

[35] Morris J (1993) The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology 43, 2412– 2414.

[36] Ott BR, Tate CA, Gordon NM, Heindel WC (1996) Gender differences in the behavioral manifestations of Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 44, 583–587.

[37]Katz S (1983) Assessing self-maintenance: Activities of daily living, mobility, and instrumental activities of daily living. J Am Geriatr Soc 31, 721–727.

[38] Lawton MP, Brody EM (1969) Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 9, 179–186.

[39] Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J (1994) The Neuropsychiatric Inventory comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 44, 2308–2308.

[40] Frisoni G, Rozzini L, Gozzetti A, Binetti G, Zanetti O, Bianchetti A, Trabucchi M, Cummings J (1999) Behavioral syndromes in Alzheimer’s disease: Description and correlates. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 10, 130–138.

[41] Smirne N, Notaro P, Addesi D, Laganà V, Altomari N, Torchia G, Colao R, Cupidi C, Frangipane F, Puccio G, Curcio SA, Bruni AC (2018) Phenotypic expressions of Alzheimer’s disease: A gender perspective. Ital J Gender-Specific Med 4, 114–122.

[42] Siafarikas N, Selbaek G, Fladby T, Benth JŠ, Auning E, Aarsland D (2018) Frequency and subgroups of neuropsychiatric symptoms in mild cognitive impairment and different stages of dementia in Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr 30, 103–113.

[43] Nobis L, Husain M (2018) Apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Opin Behav Sci 22, 7–13.

[44] Starkstein SE, Ingram L, Garau ML, Mizrahi R (2005) On the overlap between apathy and depression in dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 76, 1070–1074.

[45] Vloeberghs R, Opmeer EM, De Deyn PP, Engelborghs S, De Roeck EE (2018) Apathy, depression and cognitive functioning in patients with MCI and dementia. Tijdschrift Gerontol Geriatr 49, 95–102.

[46] Massimo L, Kales HC, Kolanowski A (2018) State of the science: Apathy as a model for investigating behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia. J Am Geriatr Socy 66, S4–S12.

[47] Johansson M, Stomrud E, Lindberg O, Westman E, Johansson PM, van Westen D, Mattsson N, Hansson O (2020) Apathy and anxiety are early markers of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Ag85, 74–82.

[48] Masters MC, Morris JC, Roe CM (2015) “Noncognitive” symptoms of early Alzheimer disease: A longitudinal analysis. Neurology 84, 617–622.

[49] Ma L (2020) Depression, anxiety, and apathy in mild cognitive impairment: Current perspectives. Front Aging Neurosci 12, 9.

[50] Piras F, Banaj N, Porcari DE, Piras F, Spalletta G (2021) Later life depression as a risk factor for developing dementia: Epidemiological evidence, predictive models, preventive strategies and future trends. Minerva Med 112, 456–466.

[51] Taipa R, Sousa AL, Melo Pires M, Sousa N (2016) Does the interplay between aging and neuroinflammation modulate Alzheimer’s disease clinical phenotypes? A clinicopathological perspective. J Alzheimers Dis 53, 403–417.

[52] Wattmo C, Wallin ÅK (2017) Early-versus late-onset Alzheimer’s disease in clinical practice: Cognitive and global outcomes over 3 years. Alzheimer’s Res Ther 9, 70.

[53] Rabinovici GD, Furst AJ, Alkalay A, Racine CA, O’Neil JP, Janabi M, Baker SL, Agarwal N, Bonasera SJ, Mormino EC, Jagust WJ (2010) Increased metabolic vulnerability in early-onset Alzheimer’s disease is not related to amyloid burden. Brain 133, 512–528.

[54] Möller C, Vrenken H, Jiskoot L, Versteeg A, Barkhof F, Scheltens P, van der Flier WM (2013) Different patterns of gray matter atrophy in early-and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 34, 2014–2022.

[55] Koedam EL, Lauffer V, van der Vlies AE, van der Flier WM, Scheltens P, Pijnenburg YA (2010) Early-versus late-onset Alzheimer’s disease: More than age alone. J Alzheimers Dis 19, 1401–1408.

[56] Bradford A, Kunik ME, Schulz P, Williams SP, Singh H (2009) Missed and delayed diagnosis of dementia in primary care: Prevalence and contributing factors. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 23, 306.

[57] Taragano FE, Allegri RF, Lyketsos C (2008) Mild behavioral impairment: A prodromal stage of dementia. Dement Neuropsychol 2, 256–260.

[58] Ismail Z, Agüera-Ortiz L, Brodaty H, Cieslak A, Cummings J, Fischer CE, Gauthier S, Geda YE, Herrmann N, Kanji J, Lanctôt KL (2017) The Mild Behavioral Impairment Checklist (MBI-C): A rating scale for neuropsychiatric symptoms in pre-dementia populations. J Alzheimers Dis 56, 929–938.

[59] Tellechea P, Pujol N, Esteve-Belloch P, Echeveste B, García-Eulate MR, Arbizu J, Riverol M (2018) Early-and late-onset Alzheimer disease: Are they the same entity? Neurologia (Engl Ed) 33, 244–253.

[60] Jack CR, Therneau TM, Weigand SD, Wiste HJ, Knopman DS, Vemuri P, Lowe VJ, Mielke MM, Roberts RO, Machulda MM, Graff-Radford J (2019) Prevalence of biologically vs clinically defined Alzheimer spectrum entities using the National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer’s Association research framework. JAMA Neurol 76, 1174–1183.

[61] Lechowski L, Benoit M, Chassagne P, Vedel I, Tortrat D, Teillet L, Vellas B (2009) Persistent apathy in Alzheimer’s disease as an independent factor of rapid functional decline: The REAL longitudinal cohort study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 24, 341–346.

Credits: Altomari, Natalia, et al. ‘A Comparison of Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD) and BPSD Sub-Syndromes in Early-Onset and Late-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease. 1 Jan. 2022 : 691 – 699.