Among the most common causes of kidney failure (KF), monogenic kidney diseases (MKDs) exhibit a broad range of clinical manifestations. According to next-generation sequencing research, nearly 10% of patients with KF have MKDs, including large multinational cohorts. This has made MKDs more significant in recent years. A considerable amount of the aetiology of KF is caused by autosomal dominant tubulointerstitial diseases, primarily by UMOD and MUC1 variants, Alport syndrome/Alport kidney disease (COL4A3-4-5 variants), and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (particularly PKD1, PKD2, and IFT140 variants). Additionally, in African-Americans, KF development is highly linked to APOL1 high-risk polymorphisms (G1 and G2). A family history of kidney disease strongly predicts monogenic kidney problems. As a result, in nephrology practice, a thorough evaluation of family history is essential. Genetic screening should be given special consideration in cases of early onset kidney disease, cystic or congenital kidney disease, kidney disease with an unknown aetiology, unexplained multisystemic findings, immunosuppressive treatment responsiveness, and risk stratification in kidney transplantation (e.g. living relative donor screening or post-transplant recurrence of atypical haemolytic uremic syndrome), in addition to patients with a family history of kidney disease or consanguinity. For prognostic guidance in diseases such as autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease or Alport syndrome, genetic screening is also helpful.

However, little is known about how kidney disease progresses differently in patients with KF who have underlying genetic and non-genetic diseases. The 5-year risk of KF was higher in RaDaR participants than in 2.81 million UK patients with all-cause chronic kidney disease (CKD) (28% vs. 1%, P <.0001), according to the UK National Registry of Rare Kidney Diseases (RaDaR) cohort study, which included 27 285 patients with rare kidney disorders, primarily glomerular or genetic diseases. However, with a standardised death rate of 0.42 (95% CI 0.32–0.52; P <.0001), the study group outperformed other patients with stage 3–5 CKD in terms of survival rates.

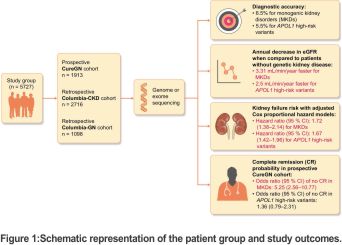

In light of this, Elliott et al. recently published a study in which they examined the prognostic differences between genetic and non-genetic kidney diseases in three distinct cohorts, including 5727 patients who had genome or exome sequencing: 1913 patients in prospective CureGN, 1098 patients in retrospective Columbia-GN, and 2716 patients in retrospective Columbia-CKD cohorts. Individuals with immunoglobulin A nephropathy (IgAN), minimal change disease (MCD), focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), and membranous nephropathy (MN) were included in the CureGN cohort (baseline median estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and urine protein–creatinine ratio (UPCR) were 83.33 mL/min and 3.39 g/g, respectively) and Columbia-GN (baseline median eGFR and UPCR were 48.16 mL/min and not available, respectively). Other than IgAN, MCD, FSGS, and MN, patients with various kidney disease aetiologies were included in the Columbia-CKD cohort (baseline median eGFR and UPCR were 27.24 mL/min and not available, respectively).

Consequently, hereditary kidney illnesses affected 12% of 5727 individuals (6.5% had MKDs and 5.5% had high-risk APOL1 mutations) (Fig. 1). The CureGN, Columbia-GN, and Columbia-CKD cohorts received diagnoses of MKDs in 371 patients in total [53/1913 (2.8%), 39/1098 (3.6%), and 279/2716 (10.3%), respectively]. In the CureGN, Columbia-GN, and Columbia-CKD cohorts, 318 individuals carried high-risk APOL1 mutations [122/1913 (6.4%), 66/1098 (6%) and 130/2716 (4.8%), respectively].

Cox proportional hazard models were used to assess the study groups’ risk of KF.

Cox proportional hazard models were used to assess the study groups’ risk of KF.

Two models for the Columbia-CKD group were employed:

Unadjusted (onset of the disorder at birth)

Modified (added APOL1 genotype, sex, diabetes, hypertension, immunosuppressive or renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors, and genetic ancestry cluster)

For the Columbia-GN group, three models were employed:

Unaltered (the time at which the kidney biopsy or clinical diagnosis begins)

minimally modified (APOL1 genotype, age at diagnosis, pathologic diagnosis, and added sex)

Additional diabetes, hypertension, immunosuppressive medication use during kidney biopsy, RAAS inhibitor use during enrolment, and genetic ancestry cluster are all included in the matching adjusted model.

For the CureGN group, four models were assessed:

Unadjusted (when the kidney biopsy begins)

minimally modified (APOL1 genotype, extra sex, and age at biopsy)

Matching adjusted for genetic heritage cluster, immunosuppressive therapy use at the time of kidney biopsy, extra diabetes, hypertension, and RAAS inhibitor use at enrolment

Completely modified (extra eGFR and UPCR at biopsy time)

For maximally adjusted models from all research groups, the corresponding hazard ratios (95% CIs) were 1.72 (1.38–2.14) for monogenic kidney diseases and 1.67 (1.42–1.96) for high-risk APOL1 variations.

At the same time, eGFR decreased 3.31 mL/min/year in MKDs and 2.5 mL/min/year in high-risk APOL1 variations, respectively, more quickly than in non-genetic illnesses. According to the covariates as fully adjusted Cox proportional hazard model, patients with MKD had a statistically lower chance of complete remission (UPCR <0.3 g/g or 24-hour proteinuria <0.3 g/day) of glomerular diseases [odds ratio (95% CI) for no remission 5.25 (2.56–10.77)], but not patients with high-risk APOL1 variants [odds ratio for no remission 1.36 (0.79–2.31)] in the prospective CureGN group.

One of the biggest multicohort studies comparing kidney outcomes between individuals with and without MKDs or high-risk APOL1 mutations has been published in the literature by Elliott et al. In this investigation, genetic screening yielded good predictive information for kidney disease development in addition to the high diagnosis accuracy of hereditary renal illnesses via genomic/exomic sequencing. It should be noted that the diagnostic yield in certain individuals may have been understated due to the failure to evaluate intronic, intergenic, and copy number variants as well as challenging sequencing sections such as the tandem repeat domain of MUC1.

According to this study, identifying hereditary kidney illnesses is essential for medical treatment and kidney survival prediction, especially in the context of precision medicine. Serious structural dysfunction brought on by impaired protein synthesis—which results from the altered expression of pertinent genes—may be linked to a worse prognosis in genetic kidney illnesses when compared to non-genetic causes. Follow-up should also take into account the patient’s resistance to immunosuppressive treatments and the necessity of avoiding them in cases with genetic glomerular diseases because these medications frequently have serious side effects, offer little benefit, and are expensive.

Additionally, genetic testing and diagnosis can help identify and screen for extrarenal symptoms of genetic illnesses and enable focused therapy for a small subset of genetic diseases. Additionally, this method facilitates family member screening and provides genetic counselling possibilities.

The findings of this study suggest that genetic screening ought to be used in nephrology practice as a predictive as well as diagnostic tool.

CREDITS: Prognostic insights from a multi-cohort study on hereditary versus non-genetic renal disease, Clinical renal Journal, Volume 18, Issue 3, March 2025, sfaf033, https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfaf033 Ahmet Burak Dirim and Roser Torra