Inder S. Anand, MD, DPhil (Oxon) and Pankaj Gupta, MD

Abstract

Anemia and iron deficiency are important and common comorbidities that often coexist in patients with heart failure. Both conditions, together or independently, are associated with poor clinical status and worse outcomes. Whether anemia and iron deficiency are just markers of heart failure severity or whether they mediate heart failure progression and outcomes and therefore should be treated is not entirely clear. Treatment of anemia in patients with heart failure with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents has been evaluated intensively during the past several years. Unfortunately, these agents did not improve outcomes but were associated with a higher risk of adverse events. Iron deficiency in patients with heart failure can be absolute, when total body iron is decreased, or functional when total body iron is normal or increased but is inadequate to meet the needs of target tissues because of sequestration in the storage pool. Whereas iron replacement is appropriate in patients with anemia resulting from absolute iron deficiency, it has been unclear whether and how absolute or functional iron deficiency should be treated in nonanemic patients with heart failure. Recently, small studies found that administration of intravenous iron in patients with heart failure and absolute or functional iron deficiency with or without anemia improves symptoms and exercise capacity, but long-term outcomes and safety data are not yet available. In this review, we discuss the causes and pathogenesis of and treatment options for anemia and iron deficiency in patients with heart failure.

Remarkable advances in our understanding of heart failure (HF) pathogenesis have led to rational therapies with considerable improvement in patient outcomes.1 Despite this, however, the prognosis of HF remains poor.2 Anemia and iron deficiency (ID) are 2 important comorbidities common in patients with HF and are associated with poor clinical status and worse outcomes. If anemia and ID are indeed mediators of poor outcomes in patients with HF, correcting these comorbidities would be attractive and novel therapeutic targets to improve outcomes. Although several small studies showed that the use of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) to increase hemoglobin in patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) is associated with beneficial effects on clinical outcomes,3,4 the neutral results of the large pivotal RED-HF trial (Reduction of Events With Darbepoetin Alfa in Heart Failure)5 suggest that anemia by itself is probably not a mediator of poor outcomes but rather a marker of HF severity. Although data from recent trials suggest that treating ID itself may be of benefit, significant knowledge gaps exist in our understanding of when, how, and for how long anemia or ID should be treated in HF and the mechanisms underlying the observed effects of treatment. In this review, we describe the magnitude of the problem of anemia and ID in patients with HF, discuss their impact on long-term outcomes, and examine whether and how they should be managed in light of recent clinical trial data.

Prevalence of Anemia in HF

The prevalence of anemia in patients with HF (defined as hemoglobin <13 g/dL in men and <12 g/dL in women)6 is ≈30% in stable and ≈50% in hospitalized patients, regardless of whether patients have HFrEF or HF with preserved ejection fraction, compared with <10% in the general population (although prevalence increases with age, exceeding 20% in subjects ≥85 years old).3,7–10 Compared with nonanemic patients with HF, anemic patients are older and more likely to be female and to have diabetes, chronic kidney disease (CKD), severe HF with worse functional status, lower exercise capacity, worse health-related quality of life (QoL), greater edema, lower blood pressure, the greater requirement of diuretics, and higher neuro- hormonal and proinflammatory cytokine activation.3,9,11–13 However, anemic subjects have a better left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (LVEF): Hemoglobin is inversely related to LVEF,8,11,14 and an increase in hemoglobin over time is associated with a decrease, not an increase, in LVEF.11,15

Causes of Anemia in HF

In the general elderly population, anemia is caused by nutritional deficiencies (primarily iron), chronic inflammation/CKD, or unexplained anemia of the elderly (hyperproliferative anemia with blunted erythropoietin response) in approximately one-third of each, with primary hematologic diseases or other conditions accounting for smaller proportions.10 Guidance is available on evaluation and management of anemia in the elderly.10 Identification of absolute ID mandates a search for its cause, particularly gastro-intestinal blood loss from benign or malignant conditions.16

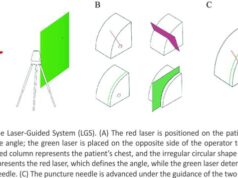

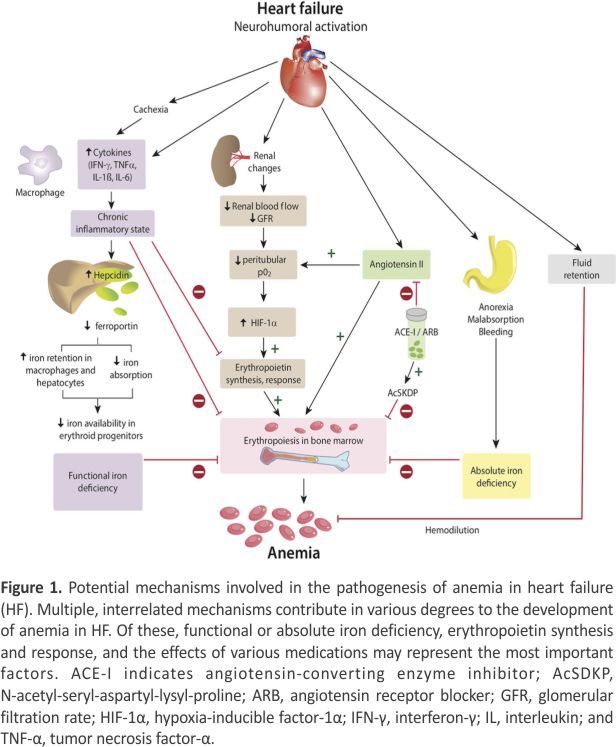

The pathogenesis of anemia in HF (reviewed previously 3) is multi-factorial (Figure 1). ID is common in HF and is discussed separately. However, deficiencies of hematinic vitamins (B12 or folate) are infrequent. Erythropoietin, which stimulates the production of red blood cells (RBCs), is produced primarily within the renal cortex and outer medulla by specialized peritubular fibroblasts and is often abnormal in HF. Low Po2 is the primary stimulus for erythropoietin production. Renal dysfunction is common in HF, but structural renal disease, which could reduce erythropoietin production, is infrequent. However, an imbalance between oxygen supply and demand related to increased proximal tubular sodium reabsorption caused by low renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate17,18 reduces renal Po2, activates hypoxia-inducible factor-1α and induces erythropoietin gene transcription. Therefore, erythropoietin levels are increased in proportion to HF severity but are lower than expected for the degree of anemia, suggesting blunted erythropoietin production.12,19 However, the relationship between renal blood flow and erythropoietin secretion during HF is complex and not fully understood.20

Inflammation is an important component of HF. Tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-6 and several other proinflammatory cytokines,12,21 and C-reactive protein are increased in HF11 and inversely related to hemoglobin level.13 Interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α also inhibit renal erythropoietin production by activating transcription factors GATA binding protein 2 (which binds nucleotide consensus sequence GATA in target gene promoters) and nuclear factor κ light-chain enhancer of activated B cells and may explain the blunted erythropoietin response. These cytokines also inhibit bone marrow erythroid progenitor cell proliferation. However, in some patients with HF, erythropoietin levels are excessively elevated, and high erythropoietin levels are associated with worse outcomes.19

The renin-angiotensin system plays an important role in erythropoietin pathophysiology through multiple pathways. First, angiotensin II decreases Po2 by reducing renal blood flow and increasing oxygen demand thereby stimulating erythropoietin production. Angiotensin II also directly stimulates bone marrow erythroid progenitor cell production. Therefore, angiotensin-converting inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers cause a modest reduction in hemoglobin11 by decreasing the production of erythropoietin22 and erythroid progenitors and by preventing breakdown of the hematopoiesis inhibitor N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline.23 Finally, anemia might be related to hemodilution,20 although clinically euvolemic patients have normal plasma volume,24 and measurement of hemoglobin reflects “true anemia” as assessed by RBC volume in the vast majority of anemic patients with HF.14

Opasich and colleagues12 identified a specific cause of anemia in only 43% of 148 patients with stable HF. ID was seen in only 5% of patients. In the remaining 57% of patients, proinflammatory cytokine activation, inadequate erythropoietin production, or defective iron utilization was found despite adequate iron stores, indicative of anemia of chronic disease (functional ID). Therefore, an activated proinflammatory state and anemia of chronic disease25 could be the most frequent underlying cause of anemia in HF. Recent reports show that mutation (eg, clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential) or deficiency of genes that regulate hematopoiesis results in an increase in inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-1β and -6, and is associated with increased incidence of coronary heart disease in humans and with worsening of cardiac remodelling in mice.26,27 Future studies may further elucidate such mechanistic interactions between the hematopoietic and cardiovascular systems.

Pathophysiological Consequences of Anemia

In patients with very severe anemia (hemoglobin, 4–6 g/dL)28,29 and normal LV function, usually seen with helminthic infections in developing countries, reduced oxygen-carrying capacity evokes nonhemodynamic and hemodynamic compensatory mechanisms (reviewed previously 3). There is an increase in RBC 2,3-diphosphoglycerate that displaces the hemoglobin-oxygen dissociation curve to the right, increasing tissue oxygen delivery. A low number of circulating RBCs reduces systemic vascular resistance28 by decreasing whole-blood viscosity, and low hemoglobin enhances nitric oxide-mediated vasodilation.29,30 The resulting decrease in arterial blood pressure causes baroreceptor-mediated neurohormonal activation, 28 identical to that seen in low-output HF.17,18 Increased sympathetic and renin-angiotensin activity decreases renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate, resulting in renal retention of salt and water with the expansion of extracellular and plasma volumes. Therefore, severe anemia itself may cause the syndrome of high-output HF in subjects with normal LV function, and correction of severe anemia in these patients causes rapid and complete regression of high-output HF.28 Although these hemodynamic and neurohormonal responses are observed in severe anemia, it is unclear whether and to what extent these mechanisms are also operative in patients with HFrEF with less severe anemia. Detailed hemodynamic and echocardiographic studies have not been reported in patients with HFrEF before and after treating anemia. However, when hemoglobin was increased from 8.5 to 10 to 14 g/dL with erythropoietin in patients with CKD and moderate anemia, cardiac output (7.0 to 6.6 to 5.2 L/min) and LV fractional shortening (36% to 33% to 29%) decreased progressively, proportional to the increase in hemoglobin.15 Therefore, all this evidence implies that increasing hemoglobin in patients with HFrEF would increase systemic vascular resistance, raise the LV afterload, and cause the LVEF to decrease. This sequence of events could explain the observed inverse relationship of hemoglobin with LVEF8,9,12 and the findings that an increase in hemoglobin over time is associated with a decrease in LVEF.9,13 These findings might also explain why the correction of anemia in patients with HFrEF has not improved outcomes.

Association of Anemia with Outcomes

Anemia is independently associated with increased mortality and hospitalizations in patients with both HFrEF and HF with preserved ejection fraction.3,7,8,31 The association of hemoglobin level with mortality is not linear, and most of the increased risk occurs at low hemoglobin.3,32,33 Some studies have reported a J-shaped relationship between hemoglobin and mortality in the normal population34 and patients with coronary artery disease,35 acute coronary syndromes,36 and HF.31,33 The lowest mortality risk was observed in the hemoglobin range of 13 to 16 g/dL, and the risk increased with hemoglobin concentrations below or above this range. Thus, the concern is that excessive increases in hemoglobin may be associated with increased mortality. In a meta-analysis of 33 studies involving > 150,000 patients with HF, anemia doubled the relative risk of death.37 A similar relationship was observed in patients with new-onset anemia and in patients with a decrease in hemoglobin over time.11 Moreover, a spontaneous increase in hemoglobin and the resolution of anemia over time were associated with a better prognosis, similar to that of patients without anemia.38 Anemia and CKD often coexist in patients with HF. Whereas anemia doubles the risk of death in patients with HF, the adjusted risk of death is further increased 1.5-fold in the presence of CKD.39 These findings, however, do not clarify whether anemia is a mediator or just a marker of HF severity.

Mechanisms Associated with Poor Outcomes in HF with Anemia

Multiple mechanisms appear to contribute to poor outcomes in these patients. Reduced oxygen delivery to metabolizing tissues in anemic subjects triggers a host of hemodynamic, neurohormonal, and renal alterations,28 leading to increased myocardial workload, which could cause adverse LV remodelling and LV hypertrophy.40,41 Moreover, patients with HF and anemia have several comorbidities, including CKD, cardiac cachexia-associated poor nutritional status, and low albumin,8,11,39 all of which could worsen outcomes. Finally, the neurohormonal and proinflammatory cytokine activation seen in patients with HF may have diverse deleterious consequences.13,21,28

Treatment Options

Should Anemia in Patients With HF Be Treated?

Most of the aforementioned observational studies suggest that anemia is common in patients with HF and is associated with poor clinical status and a worse prognosis. It is, therefore, reasonable to consider whether treatment of anemia might improve outcomes. Unfortunately, few options are available to increase hemoglobin.

Whereas packed RBC transfusion can be used as a short-term therapy, transfusions are associated with many risks and provide only temporary benefits. Kao and colleagues42 examined the large public discharge database of 596,456 patients admitted for HF. Anemia was present in 27% of patients with HF. Whereas untreated anemia was associated with ≈a 10% increased adjusted risk of mortality, the adjusted risk of mortality was ≈70% higher in anemic patients with HF who received transfusions. Although these data might raise serious concerns about the potentially harmful effects of transfusing patients with HF, there are important limitations in the analysis of this database. For example, the severity of anemia and clinical reasons for which a transfusion was required was not available and adjusted for. These and other residual measured and unmeasured confounders could have affected the results of the multivariable analysis. Prospective randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are required to clarify the role of packed RBC transfusions in patients with anemia and HF. Nevertheless, the TRICS III trial (Transfusion Requirements in Cardiac Surgery) in moderate- to high-risk patients undergoing cardiac surgery recently found that the composite primary outcome of death resulting from any cause, myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and new-onset renal failure with dialysis occurred in 11.4% of those randomized to receive intraoperative or postoperative transfusions for hemoglobin <7.5 g/dL compared with 12.5% in the more liberal strategy of transfusions for hemoglobin <9.5 g/dL, indicating that, in such patients, a restrictive transfusion strategy is non-inferior to a liberal strategy.43 These findings suggest that packed RBC transfusion in patients with HF and anemia is not necessarily beneficial and may even be associated with worse outcomes. Routine blood transfusion in asymptomatic patients, particularly those with nonacute anemia, therefore cannot be recommended.6 Because the hemoglobin threshold for packed RBC transfusions varies between clinical practice guidelines (summarized by Goodnough and Schrier10), careful consideration of individual factors, including age, comorbidities, and need for surgical intervention, is advisable when determining clinical indications for transfusion in patients with HF.

In the routine treatment of anemia, identification and correction of hematinic deficiencies (iron, B12, or folate) or hypothyroidism, if present, should be the first step. However, because many patients are thought to have anemia of chronic disease, stimulating erythropoiesis with ESAs has been investigated.

Treatment with ESAs

Between 2000 and 2010, 13 small uncontrolled or randomized placebo-controlled studies tested the effects of increasing hemoglobin with ESAs (summarized in Table I in the online-only Data Supplement). Most studies found symptomatic improvement with the use of ESAs. In 2011, Kotecha and colleagues 4 published a meta-analysis based on 11 of these RCTs of 794 patients comparing any ESA with a placebo with 2 to 12 months of follow-up. Nine studies were placebo-controlled and 5 were double-blind. Five studies used epoetin and 6 used darbepoetin. ESAs improved exercise duration by 96.8 seconds (P=0.04) and 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) by 69.3 m (P=0.009) compared with controls (Figure I in the online-only Data Supplement). Significant changes were also observed in peak oxygen consumption (Vo2; 2.29 mL·kg−1·min−1; P=0.007), New York Heart Association (NYHA) class (−0.73; P<0.001), LVEF (5.8%; P<0.001), BNP (brain natriuretic peptide; −227 pg/mL; P<0.001), and QoL indicators with a mean increase in hemoglobin of 2 g/dL. HF-related hospitalizations were reduced by 44% (P=0.005) with ESA therapy, but the reduction in all-cause mortality (42%) was of borderline significance (P=0.047; Figure II in the online-only Data Supplement). Adverse effects of ESAs were rare, with no significant increase in the development of hypertension (odds ratio, 1.37; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.65–2.87; P=0.41), stroke (odds ratio, 1.70; 95% CI, 0.52–5.62; P=0.38), MI (odds ratio, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.28–1.61; P=0.37), and thromboembolic events (odds ratio, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.17–2.11; P=0.43). In contrast, the use of darbepoetin in patients with moderate to severe HFrEF was not associated with any increase in exercise capacity in STAMINA-HeFT (Study of Anemia in Heart Failure Trial), the largest (n=319) of these small studies.44

The encouraging results of these small studies were not supported by the large pivotal RED-HF trial, published in 2013.5 RED-HF was a double-blind placebo-controlled trial that randomized 2278 patients with HFrEF, NYHA class II to IV HF, LVEF ≤40%, and mild to moderate anemia (hemoglobin, 9.0–12.0 g/dL) receiving guideline-recommended HF therapy. Patients with ID defined as a transferrin saturation (TSAT) of <15%, unless corrected, were ineligible. Patients with a history of bleeding or other correctable causes of anemia, serum creatinine >3 mg/dL, or blood pressure >160/100 mm Hg were excluded. Patients were randomized 1:1 to receive either darbepoetin alfa to achieve a hemoglobin target of 13 g/dL or placebo. Patients in the darbepoetin group received a starting dose of 0.75 μg/kg every 2 weeks until a hemoglobin of 13.0 g/dL was reached on 2 consecutive visits. Thereafter, patients received monthly darbepoetin to maintain a hemoglobin of 13.0 g/dL but not exceeding 14.5 g/dL. Iron indexes were assessed 3 months during the trial. If TSAT fell below 20%, oral and, if necessary, intravenous iron was administered. Patients had a median age of 72.0 years; 41% were women; 65% had NYHA class III or IV HF; the median LVEF was 31%; and the median estimated glomerular filtration rate was 45.7 mL/1.73m2 body surface area. The baseline median hemoglobin was 11.2 g/dL in both groups. One month after randomization and throughout the study thereafter, the median attained hemoglobin remained ≈1.5 g/dL higher in the darbepoetin group (13.0 g/dL; interquartile range, 12.4–13.4 g/dL) compared with the placebo group (11.5 g/dL; interquartile range, 10.7–12.2 g/dL; P<0.001). After a median follow-up of 28 months, darbepoetin did not affect the primary composite outcome of death resulting from any cause or hospitalization for worsening HF (hazard ratio [HR] 1.01; 95% CI, 0.90–1.13; P=0.87) or on its components. The lack of any effect of darbepoetin was consistent across all prespecified subgroups examined; no subgroup experienced any benefit from darbepoetin. There was also no significant difference in any secondary outcome, including fatal or nonfatal MI, fatal or nonfatal strokes, hypertension, and HF. More patients had fatal or nonfatal strokes in the darbepoetin than in the placebo group, although the difference was not significant. This finding becomes important because thromboembolic adverse events were significantly higher in the darbepoetin (13.5%) compared with the placebo (10.0%; P=0.01) group. Cancer-related adverse events were similar in the 2 groups. Although the rate of clinical events was not reduced by darbepoetin, treatment of anemia improved the Overall Summary and Symptom Frequency scores on the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire. However, the average between-group difference and the difference in the proportion of patients with a clinically meaningful improvement in these scores were of questionable importance. It is important to emphasize that all patients were iron-repleted at baseline. The darbepoetin group received more iron during the study because of a greater iron requirement for erythropoiesis. Neither group became ID during the study.

In summary, this large pivotal trial failed to confirm the results of previous smaller studies that treating mild to moderate anemia in patients with HFrEF with ESAs improved clinical outcomes. Although an increase in hemoglobin was associated with a modest improvement in QoL, this was of questionable importance, particularly because the use of darbepoetin was associated with a significant increase in thromboembolic events. Similar findings in CKD and cancer populations for cardiovascular safety have raised concerns about the use of ESAs to increase hemoglobin to relatively higher levels.45 Therefore, a brief examination of the CKD data may be helpful.

Are There Real Risks of Increasing Hemoglobin With ESA Therapy?

In the 1990s, several trials were conducted to assess whether complete normalization of hemoglobin with ESAs would produce additional benefits in patients with CKD. NHCT (Normal Hematocrit Cardiac Trial) randomized 1,223 patients with CKD on hemodialysis to epoetin-alfa to achieve a hematocrit of 45% versus 30%.46 The study was terminated early because of a trend of increased risk of the composite of death or nonfatal MI and a higher incidence of vascular access thrombosis in the normal hematocrit group (39% versus 29%; P=0.001). Two trials published more recently (CREATE [Cardiovascular Risk Reduction by Early Anemia Treatment With Epoetin Beta]47 and CHOIR [Correction of Hemoglobin and Outcomes in Renal Insufficiency]48) further raised serious concerns about the cardiovascular safety of higher hemoglobin with the use of ESAs in patients with CKD. In CREATE, 603 patients (hemoglobin, 11.6±0.6 g/ dL) were randomized to epoetin -beta to normalize hemoglobin (13.0–15.0 g/dL) or to epoetin only if hemoglobin declined to <10.5 g/dL. There was a trend to an increase in the relative risk of mortality (34%; P=0.14) with higher hemoglobin. The CHOIR trial randomized 1432 patients (hemoglobin, 10.1±0.9 g/dL) to epoetin to achieve a hemoglobin of 13.5 or 11.3 g/dL. The trial was stopped early for presumed futility but showed a 34% (P=0.03) increase in the composite of death, MI, hospitalization for HF, and stroke in the high hemoglobin group. Subsequently, a meta-analysis of 9 randomized trials, including the 3 trials mentioned earlier, compared the low and high hemoglobin target strategies and found a relative increase in all-cause mortality of 17% (P=0.03), arteriovenous access thrombosis of 34% (P=0.0001), and poorly controlled blood pressure of 27% (P=0.004) in the high hemoglobin groups.45

With that background, TREAT (Trial to Reduce Cardiovascular Events With Aranesp Therapy),49 the largest RCT, was designed to compare darbepoetin with placebo (achieved hemoglobin, 12.5 versus 10.6 g/dL) in 4038 patients with diabetes mellitus and CKD. Unlike previous trials that compared using ESA to achieve high or low hemoglobin, TREAT tested the more appropriate strategy of comparing an ESA with a placebo. Darbepoetin had a neutral effect on the 2 primary composite outcomes (death or a cardiovascular event; death or a renal event) but was associated with a doubling of the risk of stroke. In a post hoc analysis of the TREAT trial of 1347 patients (33.4%) with HF at baseline, darbepoetin also had a neutral effect on all-cause mortality (HR, 1.10; 95% CI, 0.93–1.29) or nonfatal HF events (HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.87–1.20), similar to the entire cohort.50 Therefore, increasing hemoglobin to relatively higher levels in patients with CKD is associated with either neutral or deleterious effects on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality with increases in thrombotic and stroke risk. Consequently, the current (2017) US Food and Drug Administration––approved label for ESAs carries Black Box statements for patients with CKD:

(a) In controlled trials, patients experienced greater risks for death, serious adverse cardiovascular reactions, and stroke when administered ESAs to target a hemoglobin level of greater than 11 g/dL, (b) No trial has identified a hemoglobin target level, ESA dose, or dosing strategy that does not increase these risks, and (c) Use the lowest ESA dose sufficient to reduce the need for RBC transfusions.50a

Consistent with the aforementioned guidance, Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative guidelines recommend interrupting or holding ESAs at a hemoglobin of 11.0 g/dL in patients with CKD.51 The US Food and Drug Administration and the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes guidelines6 recommend initiating ESA therapy at a hemoglobin cutoff of <10 g/dL in patients with CKD on dialysis and individualizing ESA initiation at this level in patients with CKD not on dialysis, although the rationale for initiating ESAs at hemoglobin <10 g/dL rather than even lower hemoglobin is not entirely clear if the only indication is to avoid transfusions. However, in a subgroup analysis of 816 TREAT-like patients with CKD and diabetes mellitus in RED-HF with baseline hemoglobin 11.0±0.8 g/dL, the use of darbepoetin to raise hemoglobin had an overall neutral effect on mortality (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.73–1.09) but was associated with a 2-fold increase in stroke risk (HR, 2.07; 95% CI, 0.98–4.38), supporting the US Food and Drug Administration and Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes guidelines on interrupting/holding ESAs at an upper level of hemoglobin ≥11 g/dL.

The overall consequences of correcting anemia in HF with ESAs are a tradeoff between the favourable effects of improving oxygen delivery and the putative cardioprotective effects of ESAs52 and the unfavourable effects of higher hemoglobin on increasing viscosity, vascular resistance, and blood pressure and ESAs on hypercoagulability.11,28,29 Moreover, the starting, achieved, change-in, and rates of rise in hemoglobin and the dose of ESA may influence the net effect of treatment.53

Taken together, data from small, short-term trials and meta-analyses of ESA in HF and the pivotal RED-HF trial suggest that correcting anemia with ESAs does not improve outcomes but does increase the risk of thromboembolic events. The findings do not support the use of these agents to increase hemoglobin in patients with HFrEF and mild to moderate anemia to higher levels. Therefore, although HF guidelines recommend a diagnostic workup to seek and treat correctable causes of anemia, they provide a Class III (no benefit), Level of Evidence BR recommendation: “In patients with HF and anemia, ESAs should not be used to improve morbidity and mortality.”1

Iron Deficiency and HF

Normal Iron Metabolism and Homeostasis

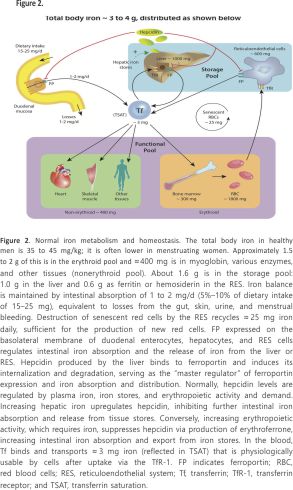

Iron is the most important essential trace element in the body. Apart from its role in maintaining the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood through erythropoiesis, iron is independently crucial for oxygen transport, delivery, and utilization. It is a key component of hemoglobin, myoglobin, and diverse enzymes involved in cellular respiration, oxidative phosphorylation, citric acid cycle, nitric oxide generation, oxygen radical production, and several critical body functions.54 Metabolic active cells, including myocytes and skeletal muscle cells, are dependent on iron for their function and structural integrity.55,56 Iron distribution and metabolism in healthy individuals are illustrated in Figure 2.

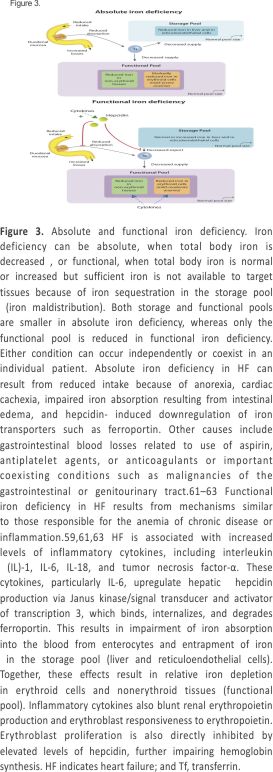

ID is a very common comorbidity in HF regardless of sex, race, anemia, and LVEF.57,58 Overall, nearly 50% of patients with HF with or without anemia have low levels of available iron.59,60 ID can be absolute, when total body iron is decreased, or functional when total body iron is normal or increased but inadequate to meet the needs of target tissues because of sequestration in the storage pool (iron maldistribution; Figure 3).

In the absence of inflammation or chronic disease, serum ferritin correlates strongly with body iron stores: 1 μg/L serum ferritin corresponds to ≈10 mg tissue iron. Serum ferritin of 100 μg/L thus reflects ≈1 g tissue iron stores. In healthy individuals, ferritin below ≈30 μg/L and TSAT below ≈16% define ID.64 In inflammatory states (including HF), however, ferritin is nonspecifically elevated as an acute-phase reactant, making the identification of absolute or functional ID complex and uncertain.16,65 Consequently, in patients with HF, ferritin <100 μg/L or <300 μg/L if TSAT is <20% has been used to include patients with both absolute and functional ID in iron replacement trials.

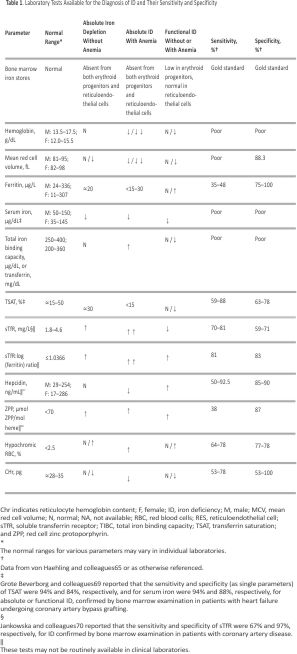

Table 1 summarizes tests available to diagnose ID.65,71,72 The soluble transferrin receptor (sTfR) level is increased in ID and unaffected by inflammation. Among the blood parameters, sTfR or TSAT may correlate strongly with bone marrow iron depletion.69,70 Although not commonly available in clinical practice, sTfR, sTfR: log (ferritin) ratio, or hepcidin levels may provide better discrimination of absolute and functional ID.73 Improving the diagnostic accuracy of tests to identify ID remains an area of active investigation.

Bone Marrow Iron Content for the Diagnosis of ID

Bone marrow iron depletion is very specific for ID, is not influenced by inflammation, and remains the gold standard for the definitive diagnosis of ID.16 However, its clinical applicability is limited because its assessment is invasive, expensive, somewhat subjective (relying on staining and observer interpretation), and difficult to perform serially. Few studies have correlated bone marrow iron with blood parameters of ID in HF. One small study in 37 hospitalized patients with decompensated HF and anemia found depleted bone marrow iron in 73% of patients despite normal serum iron, ferritin, and erythropoietin.74 Unpredictable and inconsistent variability in measured levels of ferritin and TSAT75 may partly explain discrepancies between blood parameters and bone marrow iron. Recently, Grote Beverborg and colleagues69 examined bone marrow iron in a relatively small cohort of 42 patients with HFrEF undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery and found bone marrow ID in 17 patients (40%). The commonly used definition of ID (ferritin <100 µg/L or 100–300 µg/L with TSAT <20%) had a sensitivity of 82% and a specificity of 72% for true ID. As single parameters, TSAT ≤19.8% and serum iron ≤13 µmol/L (≤72.6 µg/dL) were highly correlated with absolute or functional bone marrow ID (sensitivity, 94% for both; specificity, 84% and 88%, respectively; P<0.05). TSAT was calculated with the use of transferrin rather than total iron-binding capacity in the denominator (thus, TSAT=iron/ transferrin). It is notable that patients with low ferritin (<100 ng/mL) but normal TSAT (>20%) did not have bone marrow ID. In 387 patients with HF, TSAT or serum iron (but not ferritin) below these cutoffs was independently associated with higher all-cause mortality (P=0.015 and P=0.022, respectively), underscoring their prognostic significance. An individual patient data meta-analysis of 4 clinical trials (n=839) of the effects of intravenous ferric carboxymaltose (FCM) in patients with HFrEF found that TSAT ≤19.8% (but not serum iron [interaction P=0.077] or ferritin) identified patients who experienced reduction in cardiovascular hospitalizations and mortality (risk reduction 0.45 [95% CI, 0.29–0.71] versus 1.55 [95% CI, 0.69–3.47] for patients with TSAT >19.8%; interaction P=0.009).69 Thus, although the conventional definition of ID (ferritin <100 µg/L or 100–300 µg/L with TSAT <20%) performs reasonably well in diagnosing ID in patients with HF, a single parameter (TSAT ≤19.8% alone) performed at least as well in detecting true ID and identified subjects who responded to intravenous FCM on retrospective analysis. Ferritin levels may be more relevant for monitoring iron overload rather than the diagnosis of ID in patients with HF.

Pathophysiological Consequences of ID

Although ID is associated with several clinical consequences related to erythropoiesis, chronic ID by itself, independently of anemia, impairs oxidative metabolism, cellular energetics, and immune mechanisms that can cause a structural and functional change in the myocardium, decreasing oxygen storage in myoglobin and reducing tissue oxidative capacity, leading to mitochondrial and LV dysfunction. 76,77 Myocardial iron stores may be depleted in HF but correlate poorly with circulating markers of iron stores.78 Melenovsky and colleagues55 found that myocardial iron content in 91 patients with HF was lower than in 38 normal control organ donors (156±41 versus 200±38 µg/g dry weight, respectively; P<0.001). Reduced myocardial iron correlated with lower activity of citric acid cycle enzymes (aconitase and citrate synthase); diminished reactive oxygen species (ROS) protecting enzymes, including catalase, glutathione peroxidase, and superoxide dismutase; and reduced mitochondrial oxygen consumption. Myocardial ID in patients with HF might therefore further promote glucose rather than fatty acid utilization and, coupled with impaired protection against ROS, contribute to myocardial dysfunction and adverse remodelling. That severe myocardial ID can cause mitochondrial dysfunction is supported by the observation that isolated cardiac ID (induced by myocardial transferrin receptor 1 inactivation) induces mitochondrial respiratory dysfunction and fatal cardiomyopathy in mice.79 Iron supplementation partly prevented these adverse effects, suggesting a possible mechanism for the clinical benefit of intravenous iron in patients with HF (discussed below).

Impact of ID on Exercise Capacity, QoL, and Outcomes

Several studies showed that ID in patients with HF is associated with reduced exercise capacity, impaired QoL, and poor prognosis independently of anemia and LVEF.58,60,80,81 In a prospective study on 443 patients with stable HF and a mean LVEF of 26%, ID (serum ferritin <100 μg/L or 100–300 μg/L with TSAT <20%) was present in 35%. Peak Vo2 was significantly lower in those with ID compared with those without ID (peak Vo2, 13.3±4.0 versus 15.3±4.5 mL· min−1·kg−1). In multivariable models, ID was associated with reduced peak Vo2 independently of demographics and clinical variables, including anemia.80

Several observational studies have shown that the presence of ID in patients with HF with and without anemia is significantly associated with mortality independently of other prognostic factors.57,60,82 In 546 Polish patients with HF, absolute or functional ID (ferritin <100 µg/L or 100–300 µg/L with TSAT <20%) was present in 37% of patients; 57% were anemic and 32% were not anemic.82 On multivariable analysis, ID but not anemia was associated with a higher risk of death or heart transplantation (HR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.14–2.17; P<0.01). In a pooled international cohort comprising 1506 patients with HF, anemia, higher NYHA class, higher NT-proBNP (N-terminal pro-BNP) levels, lower RBC mean corpuscular volume, and female sex predicted ID. ID but not anemia remained a strong independent predictor of mortality in multivariable models that included NYHA class and NT-proBNP (HR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.14– 1.77; P=0.002),60 underscoring the importance of ID over anemia in predicting outcomes in HF. Similar findings were reported in an Asian cohort.57 Adverse effects of ID on exercise capacity in patients with HF may therefore be a consequence of the nonhematopoietic (rather than erythroid) effects of iron on energy metabolism and myocardial structure and function.76–79 This possibility needs to be examined prospectively.

Intravenous Iron Replacement Therapy in HF

Although the role of ID in HF pathogenesis is only just being clarified, investigators have been testing the safety and efficacy of intravenous iron in patients with HFrEF and ID for >10 years. As of 2017, 8 studies (2 small uncontrolled studies and 6 RCTs [3 small and 3 medium-sized trials]) reported the effects of intravenous iron in patients with HFrEF (Table II in the online-only Data Supplement). The primary objective of these studies was to investigate the safety and efficacy of intravenous iron on exercise capacity, NYHA class, and QoL. Clinical events were recorded as safety and secondary outcomes. Five studies (n=103 patients) used intravenous iron sucrose; 3 studies (n=504) used FCM. Therefore, the highest level of evidence for the safety and efficacy of intravenous iron therapy in patients with HFrEF and ID is with FCM. Four meta-analyses of published data reported the effects of intravenous iron on the secondary outcomes of HF hospitalizations and mortality.83–86 In addition, a robust meta-analysis of intravenous FCM on mortality and hospitalizations using individual patient data extracted from 4 RCTs, including data from 2 small previously unreported studies (FER-CARS-01 and EFFICACY-HF [Effect of Ferric Carboxymaltose on Exercise Capacity and Cardiac Function in Patients With Iron Deficiency and Chronic Heart Failure]), has recently been published.87

Bolger and colleagues88 first reported an uncontrolled open-label study of 16 anemic (hemoglobin ≤12 g/dL) patients with HF given intravenous iron sucrose for 12 to 17 days and followed up for 92±6 days. Iron treatment increased serum iron, ferritin, TSAT, and hemoglobin (11.2±0.7–12.6±1.2 g/dL; P=0.0007) and improved NYHA class, Minnesota Living With Heart Failure Questionnaire score, and 6MWD. In another open-label study, intravenous iron sucrose treatment in 32 patients with anemia and ID was associated with favorable effects on LV remodeling and NYHA functional class.89

The first randomized study was a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 40 anemic patients with HF.90 Twenty control subjects received intravenous saline and 20 received 200 mg intravenous iron sucrose weekly for 5 weeks. After 6 months, hemoglobin increased by a mean of 1.4 g/dL (P<0.01), and there was an improvement in creatinine clearance and Minnesota Living With Heart Failure Questionnaire score, a decrease in C-reactive protein and NT-proBNP, an increase in LVEF and 6MWD in the intravenous iron but not the placebo group. FERRIC-HF (Ferric Iron Sucrose in Heart Failure)91 was the first trial to use an inclusion criterion of ID defined as ferritin <100 µg/L or 100 to 300 µg/L with TSAT <20%. This definition of ID has since been used in all subsequent trials. Eighteen anemic (hemoglobin, <12.5 g/dL) and 17 nonanemic (hemoglobin, 12.5 – 14.5 g/dL) patients with ID and peak Vo2 ≤18 mL·kg−1·min−1 were randomized to open-label, observer-blinded treatment with placebo or intravenous iron sucrose 200 mg/ wk for 4 weeks during the initial ID correction phase (using the Ganzoni formula; Table 2) and additional iron sucrose 200 mg/mo as required during the maintenance phase or to no treatment for the next 3 months. The iron requirement was higher in patients with anemia than in those without anemia (1051 versus 781 mg). Iron therapy increased serum ferritin and improved NYHA class, but unlike the previous 2 studies, hemoglobin did not increase. Peak Vo2 increased significantly in anemic but not in nonanemic patients.

FAIR-HF (Ferinject Assessment in Patients With Iron Deficiency and Chronic Heart Failure) is the largest randomized study reported so far.92 Patients (n=459) with HF and ID (ferritin <100 μg/L or 100– 300 μg/L with TSAT <20%), with anemia (hemoglobin 9.5–12.0 g/dL) or without anemia (hemoglobin 12.0–13.5 g/dL), were randomly assigned 2:1 to intravenous FCM (n=304) or saline (n=155). FCM increased ferritin levels in all patients with a modest increase in hemoglobin only in anemic patients (0.9 g/dL; P<0.001 versus controls) but not in those without anemia (0.2 g/dL; P=0.21). FCM improved patients’ global assessment and NYHA class (both P<0.001), the coprimary endpoint. The beneficial effect of iron was similar in patients with and without baseline anemia. QoL and 6MWD also improved. However, there were no significant effects on all-cause mortality (3.4% versus 5.5%, FCM versus control) or first hospitalization (17.7% versus 24.8%). FCM was generally well tolerated. Adverse events were similar in both groups.

FAIR-HF (Ferinject Assessment in Patients With Iron Deficiency and Chronic Heart Failure) is the largest randomized study reported so far.92 Patients (n=459) with HF and ID (ferritin <100 μg/L or 100– 300 μg/L with TSAT <20%), with anemia (hemoglobin 9.5–12.0 g/dL) or without anemia (hemoglobin 12.0–13.5 g/dL), were randomly assigned 2:1 to intravenous FCM (n=304) or saline (n=155). FCM increased ferritin levels in all patients with a modest increase in hemoglobin only in anemic patients (0.9 g/dL; P<0.001 versus controls) but not in those without anemia (0.2 g/dL; P=0.21). FCM improved patients’ global assessment and NYHA class (both P<0.001), the coprimary endpoint. The beneficial effect of iron was similar in patients with and without baseline anemia. QoL and 6MWD also improved. However, there were no significant effects on all-cause mortality (3.4% versus 5.5%, FCM versus control) or first hospitalization (17.7% versus 24.8%). FCM was generally well tolerated. Adverse events were similar in both groups.

The design of CONFIRM-HF (A Study to Compare the Use of Ferric Carboxymaltose With Placebo in Patients With Chronic Heart Failure and Iron Deficiency)95 was very similar to that of FAIR-HF except for higher doses of FCM given for a longer duration (52 weeks). Patients (n=304) with LVEF ≤45%, elevated natriuretic peptides, and ID (ferritin <100 µg/L or 100–300 µg/L if TSAT <20%) were randomized 1:1 to intravenous FCM (n=152) or placebo (saline; n=152). FCM significantly improved the primary endpoint of 6MWD at week 24 compared with placebo, a benefit sustained at 1 year. This was associated with significant improvements in secondary endpoints, including NYHA class, patient global assessment, QoL, and fatigue score. FCM treatment was also associated with a significant reduction in the risk of hospitalizations for worsening HF (HR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.19–0.82; P=0.009) with no difference in all-cause mortality. These findings indicate that the benefits of FCM on functional capacity, symptoms, and QoL in symptomatic, iron-deficient patients with HF are sustainable over 1 year. Unlike previous studies, CONFIRM-HF95 also showed that the use of intravenous iron may be associated with a reduction in the risk of hospitalization for worsening HF.

In the most recent study, EFFECT-HF (Effect of Ferric Carboxymaltose on Exercise Capacity in Patients With Iron Deficiency and Chronic Heart Failure),96 randomized 172 patients with HFrEF and ID (ferritin <100 µg/L or 100–300 µg/L if TSAT <20%), NYHA class II to III HF, LVEF <45%, BNP >100 pg/mL or NT-proBNP >400 pg/mL, hemoglobin <15 g/dL, and peak Vo2 of 10 to 20 mL·kg−1·min−1 to FCM (n=86) or standard care (n=86, who could receive oral iron as needed). At 24 weeks, the primary endpoint of change in peak Vo2 from baseline was no different between the FCM and control groups (Δpeak Vo2, −0.16±0.373 mL·min−1·kg−1 in those receiving FCM and −0.63± 0.375 mL·min−1·kg−1 in controls; P=0.23) in an analysis in which missing data were not imputed. The patient’s global assessment and functional (NYHA) class improved on FCM versus standard of care. Outcomes were not assessed.

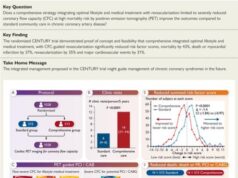

The meta-analysis by Anker and colleagues87 explored the effects of intravenous iron on objective cardiovascular outcomes and was reported before the results of EFFECT-HF were available. The authors examined individual patient data extracted from 4 RCTs comparing FCM with placebo in 839 patients with HFrEF and ID, 504 randomized to pooled FCM and 335 to pooled placebo groups. Approximately 90% of the patients were contributed by FAIR-HF and CONFIRM-HF. Patients in the 4 RTCs had very similar baseline characteristics; the same criteria were used to diagnose ID; and the same intravenous iron therapy (FCM) was tested. Therefore, this meta-analysis provides a more accurate and robust assessment of the relative effects of FCM on hard clinical outcomes compared with other recently performed meta-analyses that used different criteria for diagnosing ID, used different intravenous preparations, and included patients prescribed ESAs. 83–86 The main finding of the Anker et al87 meta-analysis is that FCM treatment is associated with lower rates of recurrent cardiovascular hospitalizations and cardiovascular mortality (rate ratio, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.40–0.88; P=0.009), recurrent HF hospitalizations and cardiovascular mortality (rate ratio, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.33–0.86; P=0.011), and recurrent cardiovascular hospitalizations and all-cause mortality (rate ratio, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.41–0.88; P=0.009). Intravenous iron was not associated with an increased risk of adverse events. However, a troublesome and hypothesis-generating finding comes from a prespecified subgroup analysis demonstrating a significant interaction between baseline tertiles of TSAT and treatment effect on all 3 composite outcomes. A TSAT-dependent effect of iron therapy was seen on all 3 composite outcomes, with the greatest benefit in the lowest TSAT tertile (<12.7%) but no benefit in subgroups with TSAT of 12.7% to 20.1% and ≥20.1% (Figure 4).

Indeed, a trend to adverse effects of intravenous iron was seen in the highest TSAT tertile. Separately, Grote Beverborg and colleagues69 reported in their meta-analysis of this same group of patients that FCM treatment was associated with an improvement in cardiovascular hospitalizations and cardiovascular mortality in those with TSAT ≤19.8% but not in those with TSAT >19.8%. If confirmed in prospective studies, these findings would suggest that there may be no clear benefit of intravenous iron in patients with only a modest degree of ID. These findings would be of great interest because, as discussed below, there are concerns about the deleterious effects of overcorrecting ID, particularly over prolonged periods.

Indeed, a trend to adverse effects of intravenous iron was seen in the highest TSAT tertile. Separately, Grote Beverborg and colleagues69 reported in their meta-analysis of this same group of patients that FCM treatment was associated with an improvement in cardiovascular hospitalizations and cardiovascular mortality in those with TSAT ≤19.8% but not in those with TSAT >19.8%. If confirmed in prospective studies, these findings would suggest that there may be no clear benefit of intravenous iron in patients with only a modest degree of ID. These findings would be of great interest because, as discussed below, there are concerns about the deleterious effects of overcorrecting ID, particularly over prolonged periods.

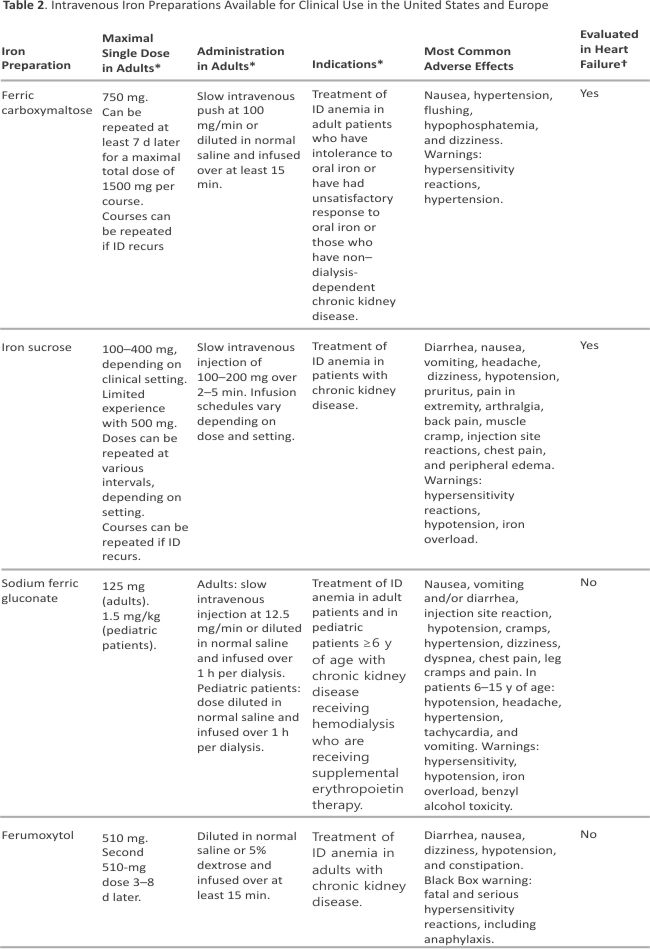

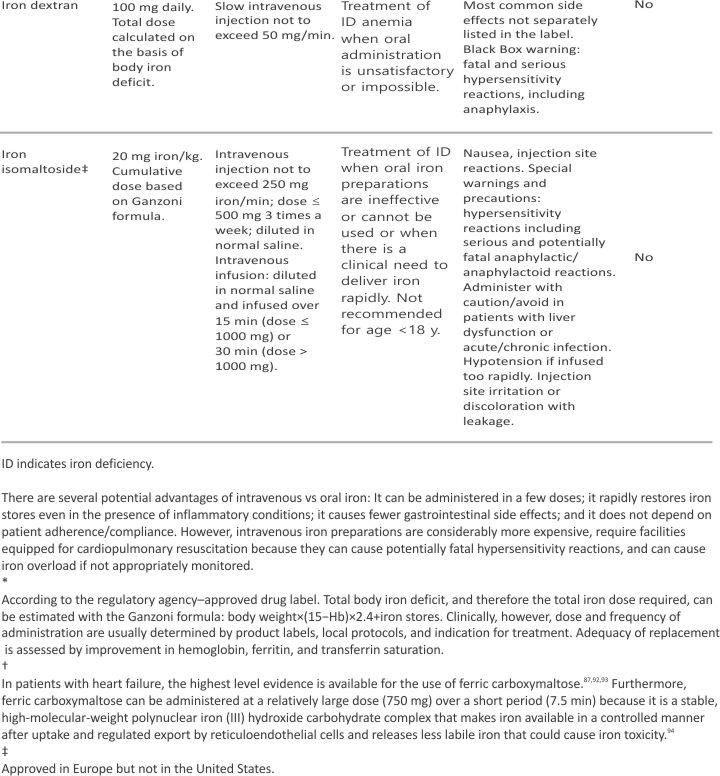

Intravenous Iron Preparations

Parenteral iron preparations (Table 2) have seen enormous development over the past 20 years. At present, 5 intravenous iron preparations are available in the United States and Europe, of which 2 preparations (iron sucrose and FCM) have been tested prospectively in patients with HF. In addition, iron isomaltoside is available in Europe but not yet in the United States. Both iron isomaltoside and FCM enable higher doses of iron to be administered to replenish iron stores more rapidly.

Oral Iron Replacement Therapy in HF

Although oral iron supplementation is convenient, readily available, and inexpensive, oral iron is not absorbed well, particularly in patients with HF because of the effects of HF on the gastrointestinal tract and elevated hepcidin, which inhibits iron absorption by reducing transmembrane ferroportin on enterocytes, thereby reducing iron transfer from enterocytes to blood.97 Moreover, oral iron is associated with adverse effects, particularly gastrointestinal intolerance, that limit compliance. Few studies have investigated the effects of oral iron in patients with ID and HF.98 The results of IRONOUT HF (Iron Repletion Effects on Oxygen Uptake in Heart Failure), the largest randomized study to examine the effects of high-dose oral iron in patients with HF, were published recently.99 In this phase 2 double-blind RCT, 225 patients with NYHA class II to IV HF (median LVEF, 25%), hemoglobin of 9 to 15 g/dL (men) or 9 to 13.5 g/dL (women), and ID (ferritin 15–100 µg/L or 100–299 µg/L with TSAT <20%) received either oral iron polysaccharide 150 mg twice daily or placebo. At 16 weeks, there was no significant difference between the groups in the primary endpoint of change in peak Vo2 from baseline or any secondary endpoint (6MWD, NT-proBNP levels, or Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire score), although oral iron increased TSAT, ferritin, and hepcidin and reduced sTfR-1 levels. These findings contrast with the results from trials of intravenous iron therapy in similar patient populations.87 Reasons for a lack of response to oral iron are not entirely clear. Robust repletion of iron stores may be required to achieve clinical benefit because oral iron-induced only modest iron repletion (median increases from baseline in TSAT of 3% and ferritin of 11 µg/L in IRONOUT HF), in contrast to median increases of 11.3% and 259.5 µg/L, respectively, with intravenous iron in FAIR-HF.92 This modest repletion of iron stores occurred despite 15-fold more oral iron administered in IRONOUT HF compared with intravenous iron in FAIR-HF (33.6 versus ≈2 g). Patients with higher baseline hepcidin levels demonstrated less improvement in TSAT and ferritin and an attenuated decline in sTfR levels, suggesting that higher hepcidin levels may limit responsiveness to oral iron, perhaps via inhibiting duodenal iron absorption.

In summary, these early studies provide encouraging data raising the possibility that intravenous but not oral iron therapy has a potential role in patients with HFrEF and absolute or functional ID with or without anemia. Most studies found that intravenous iron improved exercise capacity, NYHA class, and QoL. Although no study by itself showed significant improvements in cardiovascular mortality, meta-analyses of 4 trials demonstrated significant improvements in objective cardiovascular outcomes. Overall, intravenous iron was safe in the short term, but data on long-term safety and efficacy are lacking. Nevertheless, the 2016 European Society of Cardiology guidelines interpreted the available data as being adequate to provide a Class IIa, Level of Evidence A recommendation: “Intravenous FCM should be considered in symptomatic patients with HFrEF and iron deficiency (serum ferritin <100 μg/L, or ferritin 100–299 μg/L and TSAT <20%) to alleviate HF symptoms, and improve exercise capacity and quality of life.”99a The 2017 American Heart Association/ American College of Cardiology guidelines provide a lower Class IIb, Level of Evidence BR recommendation: “In patients with NYHA class II and III heart failure and iron deficiency (ferritin <100 µg/L or 100–300 µg/L if TSAT <20%), intravenous iron replacement might be reasonable to improve functional status and QoL.”1

Despite these recommendations, long-term clinical studies are still required to confirm the beneficial effects of intravenous iron on outcomes; to provide additional safety data, particularly on the potential adverse effects of iron overload during long-term administration in patients with HF; and to determine which parameters best reflect iron stores to guide iron supplementation. Several large long-term studies examining cardiovascular outcomes are ongoing (Table III in the online-only Data Supplement). Some ongoing studies directly examining changes in myocardial iron content, gene expression, and skeletal muscle metabolism are also likely to provide critical insights into the pathophysiological role of ID in nonerythroid tissues and the clinical effects of its repletion in patients with HF. Data from these studies are likely to provide valuable information to guide clinical decision-making.

Potential Adverse Effects of Iron Overload on the Heart

The human body does not possess any mechanism to excrete iron; instead, it regulates duodenal iron uptake.100 Above TSAT values of 70% to 85%, non–transferrin-bound iron is formed, part of which is called labile plasma iron or labile cellular iron. Labile plasma iron/ labile cellular iron catalyzes free radical (ROS) formation, which damages mitochondria, lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids.101 Under normal physiological conditions, duodenal iron uptake of dietary iron is reduced to prevent iron overload, which could lead to the formation of free/unbound iron. However, this protective mechanism is bypassed when iron is administered intravenously. Iron overload can cause cardiomyopathy and HF,102 increases the risk of bacteremia and promotes ROS formation, which can cause widespread tissue damage and endothelial dysfunction. These effects may increase the risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes. 103 Several mechanisms of iron-induced cardiac damage have been described,104 mainly related to ROS formation, which leads to cardiac myocyte apoptosis, fibrosis, and HF. Myocardial cells have low levels of antioxidant enzymes, and ROS-protective enzyme levels are further reduced by myocardial ID in HF,55 potentially making the failing heart even more susceptible to iron-mediated damage. Labile plasma iron/labile cellular iron directly enters cardiomyocytes (primarily via L-type calcium channels), increases ROS production, and may inhibit calcium influx, which further adversely influences myocardial excitation-contraction coupling. Intravenous iron given repeatedly over long periods can lead to clinically relevant tissue iron overloading. For instance, the drug label for FCM describes iron overload-induced hemosiderosis, leading to multiple joint disorders, walking disability, and asthenia in 1 patient and hypophosphatemic osteomalacia in another. It is therefore critical to prevent iron overload when correcting ID in patients with HF.

Hepcidin as A Potential Therapeutic Target in HF with Iron Deficiency

Hepcidin is the master regulator of iron absorption and distribution, and its level is increased in chronic diseases, including HF. Increased hepcidin reduces duodenal iron absorption and simultaneously reduces iron release from stores in reticulo-endothelial cells and hepatocytes, thereby causing functional ID (Figures 2 and 3). Blocking hepcidin might therefore be an effective therapeutic strategy, particularly in functional ID. In early human studies, several investigational antihepcidin agents increased iron bioavailability. Promising strategies include directly blocking hepcidin expression by an anti–hepcidin l– oligoribonucleotide (lexaptepid) or its activity by a fully human anti-hepcidin antibody or blocking hepcidin signalling by a small-molecule inhibitor (LDN-193189) or non anticoagulant heparins.16,105 Spironolactone, commonly used in patients with HF, inhibits hepcidin expression in mice, raising the possibility that this drug may be repurposed to this end.106 Whether strategies that downregulate hepcidin will be of clinical benefit merits prospective evaluation.

Conclusions

Anemia and absolute or relative ID are common comorbidities in patients with HF and are associated with poor clinical status and worse outcomes. Although the cause of anemia in HF is not entirely clear, evidence suggests that neuro-hormonal and proinflammatory cytokine activation and renal dysfunction favor the development of anemia of chronic disease. Whereas ESAs were considered to be a rational therapy to increase hemoglobin and treat anemia in HF, these agents do not improve outcomes and may be associated with thromboembolic complications. ESAs are therefore not recommended.

Early data from short-term studies in patients with HFrEF and absolute or functional ID with or without anemia suggest that intravenous but not oral iron therapy may have a potential role in improving exercise capacity, NYHA class, and QoL. However, larger, adequately powered trials with cardiovascular mortality and morbidity endpoints are needed to establish the long-term efficacy and safety of intravenous iron in patients with HF. The numerous long-term ongoing studies are likely to provide valuable information to address these concerns and to help guide future clinical decision-making.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Hector Mesa (Minneapolis VA Medical Center and University of Minnesota) for the critical review of the article and James Hungaski (Minneapolis VA Medical Center) for creating the original illustrations (Figures 1 through 3). The authors apologize to the many investigators whose work could not be discussed or cited because of space considerations.

Affiliations

Inder S. Anand, MD, DPhil (Oxon) anand001@umn.edu

VA Medical Center, Minneapolis, MN (I.A., P.G.), VA Medical Center, San Diego, CA (I.A.), University of Minnesota, Minneapolis (I.A., P.G.).

Pankaj Gupta, MD

VA Medical Center, Minneapolis, MN (I.A., P.G.), University of Minnesota, Minneapolis (I.A., P.G.).

References

1. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Colvin MM, Drazner MH, Filippatos GS, Fonarow GC, Givertz MM, Hollenberg SM, Lindenfeld J, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, Peterson PN, Stevenson LW, Westlake C. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology /American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation. 2017;136: e137–e161. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000 000000509.

2. Writing Group Members, Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, Das SR, de Ferranti S, Despres JP, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Isasi CR, Jimenez MC, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, Moy CS, Muntner P, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Rosamond W, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Woo D, Yeh RW, Turner MB, American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016; 133:e38–e360. doi: 10.1161/CIR.00 00000000000350.

3. Anand IS. Anemia and chronic heart failure implications and treatment options. J Am Coll Cardiol.2008;52:501 –511. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008. 04.044.

4. Kotecha D, Ngo K, Walters JA, Manzano L, Palazzuoli A, Flather MD. Erythropoietin as a treatment of anemia in heart failure: systematic review of randomized trials. Am Heart J. 2011;161:822– 831. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.02. 013.

5. Swedberg K, Young JB, Anand IS, Cheng S, Desai AS, Diaz R, Maggioni AP, McMurray JJ, O’Connor C, Pfeffer MA, Solomon SD, Sun Y, Tendera M, van Veldhuisen DJ; RED-HF Committees; RED-HF Investigators. Treatment of anemia with darbepoetin alfa in systolic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1210–1219. doi: 10.1056/ NEJMoa1214865.

6. Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes) (KDIGO) Anemia Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for anemia in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2: 279–335.

7. Tang YD, Katz SD. The prevalence of anemia in chronic heart failure and its impact on the clinical outcomes. Heart Fail Rev. 2008;13:387–392. doi: 10.1007/s10741-008-9089-7.

8. O’Meara E, Clayton T, McEntegart MB, McMurray JJ, Lang CC, Roger SD, Young JB, Solomon SD, Granger CB, Ostergren J, Olofsson B, Michelson EL, Pocock S, Yusuf S, Swedberg K, Pfeffer MA; CHARM Committees and Investigators. Clinical correlates and consequences of anemia in a broad spectrum of patients with heart failure: results of the Candesartan in Heart Failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity (CHARM) Program. Circulation. 2006;113:986 –994. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATION AHA.105. 582577.

9. Ezekowitz JA, McAlister FA, Armstrong PW. Anemia is common in heart failure and is associated with poor outcomes: insights from a cohort of 12 065 patients with new-onset heart failure. Circulation. 2003;107:223 –225.

10. Goodnough LT, Schrier SL. Evaluation and management of anemia in the elderly. Am J Hematol. 2014;89:88 –96. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23598.

11. Anand IS, Kuskowski MA, Rector TS, Florea VG, Glazer RD, Hester A, Chiang YT, Aknay N, Maggioni AP, Opasich C, Latini R, Cohn JN. Anemia and change in hemoglobin overtime related to mortality and morbidity in patients with chronic heart failure: results from Val-HeFT. Circulation. 2005;112:1121–1127. doi: 10.1161/ CIRCULATIONAHA.104.512988.

12. Opasich C, Cazzola M, Scelsi L, De Feo S, Bosimini E, Lagioia R, Febo O, Ferrari R, Fucili A, Moratti R, Tramarin R, Tavazzi L. Blunted erythropoietin production and defective iron supply for erythropoiesis as major causes of anaemia in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2005;26: 2232– 2237. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj /ehi388.

13. Anand IS, Rector T, Deswal A, Iverson E, Anderson S, Mann D, Cohn JN, Demets D. Relationship between proinflammatory cytokines and anemia in heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(suppl 1):485.

14. Montero D, Lundby C, Ruschitzka F, Flammer AJ. True anemia-red blood cell volume deficit-in heart failure: a systematic review. Circ Heart Fail. 2017;10:e003610. doi: 10.1161/ CIRCHEARTFAILURE.116.003610

15. McMahon LP, Mason K, Skinner SL, Burge CM, Grigg LE, Becker GJ. Effects of haemoglobin normalization on quality of life and cardiovascular parameters in end-stage renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15: 1425–1430.

16. Lopez A, Cacoub P, Macdougall IC, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Iron deficiency anaemia. Lancet. 2016;387:907– 916. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60865-0.

17. Anand IS, Ferrari R, Kalra GS, Wahi PL, Poole-Wilson PA, Harris PC. Patho- genesis of edema in constrictive pericarditis: studies of body water and sodium, renal function, hemodynamics, and plasma hormones before and after pericardiectomy. Circulation. 1991;83:1880–1887.

18. Anand IS, Ferrari R, Kalra GS, Wahi PL, Poole-Wilson PA, Harris PC. Edema of cardiac origin: studies of body water and sodium, renal function, hemodynamic indexes, and plasma hormones in untreated congestive cardiac failure. Circulation. 1989;80: 299–305.

19. van der Meer P, Voors AA, Lipsic E, Smilde TD, van Gilst WH, van Veldhuisen DJ. Prognostic value of plasma erythropoietin on mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:63–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.03.052.

20. Westenbrink BD, Visser FW, Voors AA, Smilde TD, Lipsic E, Navis G, Hillege HL, van Gilst WH, van Veldhuisen DJ. Anaemia in chronic heart failure is not only related to impaired renal perfusion and blunted erythropoietin production but to fluid retention as well. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:166–171. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl419.

21. Deswal A, Petersen NJ, Feldman AM, Young JB, White BG, Mann DL. Cytokines and cytokine receptors in advanced heart failure: an analysis of the cytokine database from the Vesnarinone trial (VEST). Circulation. 2001;103:2055–2059.

22. Fyhrquist F, Karppinen K, Honkanen T, Saijonmaa O, Rosenlöf K. High serum erythropoietin levels are normalized during treatment of congestive heart failure with enalapril. J Intern Med. 1989;226:257–260.

23. van der Meer P, Lipsic E, Westenbrink BD, van de Wal RM, Schoemaker RG, Vellenga E, van Veldhuisen DJ, Voors AA, van Gilst WH. Levels of hematopoiesis inhibitor N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline partially explain the occurrence of anemia in heart failure. Circulation. 2005;112: 1743–1747. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105. 549121.

24. Anand IS, Veall N, Kalra GS, Ferrari R, Sutton G, Lipkin D, Harris P, Poole-Wilson PA. Treatment of heart failure with diuretics: body compartments, renal function and plasma hormones. Eur Heart J. 1989;10:445–450.

25. Weiss G. Iron metabolism in the anemia of chronic disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790:682–693. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.08.006.

26. Jaiswal S, Natarajan P, Silver AJ, Gibson CJ, Bick AG, Shvartz E, McConkey M, Gupta N, Gabriel S, Ardissino D, Baber U, Mehran R, Fuster V, Danesh J, Frossard P, Saleheen D, Melander O, Sukhova GK, Neuberg D, Libby P, Kathiresan S, Ebert BL. Clonal hematopoiesis and risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:111 –121. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1701719.

27. Sano S, Oshima K, Wang Y, MacLauchlan S, Katanasaka Y, Sano M, Zuriaga MA, Yoshiyama M, Goukassian D, Cooper MA, Fuster JJ, Walsh K. Tet2-mediated clonal hematopoiesis accelerates heart failure through a mechanism involving the IL-1β/NLRP3 inflammasome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:875–886. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.12.037.

28. Anand IS, Chandrashekhar Y, Ferrari R, Poole-Wilson PA, Harris PC. Pathogenesis of oedema in chronic severe anaemia: studies of body water and sodium, renal function, haemodynamic variables, and plasma hormones. Br Heart J. 1993;70:357–362.

29. Anand IS, Chandrashekhar Y, Wander GS, Chawla LS. The endothelium-derived relaxing factor is important in mediating the high output state in chronic severe anemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:1402–1407. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00007-Q.

30. Ni Z, Morcos S, Vaziri ND. Up-regulation of renal and vascular nitric oxide synthase in iron-deficiency anemia. Kidney Int. 1997;52:195–201.

31. Go AS, Yang J, Ackerson LM, Lepper K, Robbins S, Massie BM, Shlipak MG. Hemoglobin level, chronic kidney disease, and the risks of death and hospitalization in adults with chronic heart failure: the Anemia in Chronic Heart Failure: Outcomes and Resource Utilization (ANCHOR) Study. Circulation. 2006;113:2713–2723. doi: 10.1161/ CIRCULATIONAHA.105. 577577.

32. Komajda M, Anker SD, Charlesworth A, Okonko D, Metra M, Di Lenarda A, Remme W, Moullet C, Swedberg K, Cleland JG, Poole-Wilson PA. The impact of new-onset anaemia on morbidity and mortality in chronic heart failure: results from COMET. Eur Heart J.2006; 27:1440–1446. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj /ehl012.

33. Sharma R, Francis DP, Pitt B, Poole-Wilson PA, Coats AJ, Anker SD. Haemoglobin predicts survival in patients with chronic heart failure: a substudy of the ELITE II trial. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1021–1028. doi: 10.1016/ j.ehj.2004.04.023.

34. Gagnon DR, Zhang TJ, Brand FN, Kannel WB. Hematocrit and the risk of cardiovascular disease: the Framingham study: a 34-year follow-up. Am Heart J. 1994;127:674–682.

35. Brown DW, Giles WH, Croft JB. Hematocrit and the risk of coronary heart disease mortality. Am Heart J. 2001;142:657–663. doi: 10.1067/ mhj.2001.118467.

36. Sabatine MS, Morrow DA, Giugliano RP, Burton PB, Murphy SA, McCabe CH, Gibson CM, Braunwald E. Association of hemoglobin levels with clinical outcomes in acute coronary syndromes. Circulation.2005;111: 2042–2049. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR. 0000162477.70955.5F.

37. Groenveld HF, Januzzi JL, Damman K, van Wijngaarden J, Hillege HL, van Veldhuisen DJ, van der Meer P. Anemia and mortality in heart failure patients a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008; 52:818–827. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008. 04.061.

38. Tang WH, Tong W, Jain A, Francis GS, Harris CM, Young JB. Evaluation and long-term prognosis of new-onset, transient, and persistent anemia in ambulatory patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51: 569–576. doi: 10.1016/j. jacc. 2007.07.094.

39. Herzog CA, Muster HA, Li S, Collins AJ. Impact of congestive heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and anemia on survival in the Medicare population. J Card Fail. 2004;10:467–472.

40. Datta BN, Silver MD. Cardiomegaly in chronic anaemia in rats; gross and histologic features. Indian J Med Res. 1976;64:447–458.

41. Anand I, McMurray JJ, Whitmore J, Warren M, Pham A, McCamish MA, Burton PB. Anemia and its relationship to clinical outcome in heart failure. Circulation. 2004;110:149–154. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000134279.79571.73.

42. Kao DP, Kreso E, Fonarow GC, Krantz MJ. Characteristics and outcomes among heart failure patients with anemia and renal insufficiency with and without blood transfusions (public discharge data from California 2000– 2006). Am J Cardiol. 2011;107: 69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010. 08.046.

43. Mazer CD, Whitlock RP, Fergusson DA, Hall J, Belley-Cote E, Connolly K, Khanykin B, Gregory AJ, de Médicis É, McGuinness S, Royse A, Carrier FM, Young PJ, Villar JC, Grocott HP, Seeberger MD, Fremes S, Lellouche F, Syed S, Byrne K, Bagshaw SM, Hwang NC, Mehta C, Painter TW, Royse C, Verma S, Hare GMT, Cohen A, Thorpe KE, Jüni P, Shehata N; TRICS Investigators and Perioperative Anesthesia Clinical Trials Group. Restrictive or liberal red-cell transfusion for cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2133–2144. doi: 10.1056/ NEJMoa1711818.

44. Ghali JK, Anand IS, Abraham WT, Fonarow GC, Greenberg B, Krum H, Massie BM, Wasserman SM, Trotman ML, Sun Y, Knusel B, Armstrong P; Study of Anemia in Heart Failure Trial (STAMINA-HeFT) Group. A randomized double-blind trial of darbepoetin alfa in patients with symptomatic heart failure and anemia. Circulation.2008; 117:526–535. doi: 10.1161/ CIRCULATIONAHA.107.698514.

45. Phrommintikul A, Haas SJ, Elsik M, Krum H. Mortality and target haemoglobin concentrations in anaemic patients with chronic kidney disease treated with erythropoietin: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2007;369: 381–388. doi: 10.1016/S0140-67 36(07)60194-9.

46. Besarab A, Bolton WK, Browne JK, Egrie JC, Nissenson AR, Okamoto DM, Schwab SJ, Goodkin DA. The effects of normal as compared with low hematocrit values in patients with cardiac disease who are receiving hemodialysis and epoetin. N Engl J Med. 1998;339: 584–590. doi: 10.1056/NEJM19980 8273390903.

47. Drüeke TB, Locatelli F, Clyne N, Eckardt KU, Macdougall IC, Tsakiris D, Burger HU, Scherhag A; CREATE Investigators. Normalization of hemoglobin level in patients with chronic kidney disease and anemia. N Engl J Med. 2006; 355:2071–2084. doi: 10.1056/NEJM oa062276.

48. Singh AK, Szczech L, Tang KL, Barnhart H, Sapp S, Wolfson M, Reddan D; CHOIR Investigators. Correction of anemia with epoetin alfa in chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2006; 355:2085–2098. doi: 10.1056/NEJM oa065485.

49. Pfeffer MA, Burdmann EA, Chen CY, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Eckardt KU, Feyzi JM, Ivanovich P, Kewalramani R, Levey AS, Lewis EF, McGill JB, McMurray JJ, Parfrey P, Parving HH, Remuzzi G, Singh AK, Solomon SD, Toto R; TREAT Investigators. A trial of darbepoetin alfa in type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2019–2032. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907845.

50. Desai A, Lewis E, Solomon S, McMurray JJ, Pfeffer M. Impact of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents on morbidity and mortality in patients with heart failure: an updated, post-TREAT meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;12:936–942. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq094.

50a. US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/.

51. Kliger AS, Foley RN, Goldfarb DS, Goldstein SL, Johansen K, Singh A, Szczech L. KDOQI US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for anemia in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62:849–859. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.06.008.

52. Calvillo L, Latini R, Kajstura J, Leri A, Anversa P, Ghezzi P, Salio M, Cerami A, Brines M. Recombinant human erythropoietin protects the myocardium from ischemia-reperfusion injury and promotes beneficial remodeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100: 4802– 4806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630 444100.

53. Solomon SD, Uno H, Lewis EF, Eckardt KU, Lin J, Burdmann EA, de Zeeuw D, Ivanovich P, Levey AS, Parfrey P, Remuzzi G, Singh AK, Toto R, Huang F, Rossert J, McMurray JJ, Pfeffer MA; Trial to Reduce Cardiovascular Events with Aranesp Therapy (TREAT) Investigators. Erythropoietic response and outcomes in kidney disease and type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1146–1155. doi: 10.1056/ NEJMoa1005109.

54. Dunn LL, Suryo Rahmanto Y, Richardson DR. Iron uptake and metabolism in the new millennium. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.12.003.

55. Melenovsky V, Petrak J, Mracek T, Benes J, Borlaug BA, Nuskova H, Pluhacek T, Spatenka J, Kovalcikova J, Drahota Z, Kautzner J, Pirk J, Houstek J. Myocardial iron content and mitochondrial function in human heart failure: a direct tissue analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19:522–530. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.640.

56. Jankowska EA, Ponikowski P. Molecular changes in the myocardium in the course of anemia or iron deficiency. Heart Fail Clin. 2010;6:295–304. doi:10. 1016/j.hfc.2010.03.003.

57. Yeo TJ, Yeo PS, Ching-Chiew Wong R, Ong HY, Leong KT, Jaufeerally F, Sim D, Santhanakrishnan R, Lim SL, M Y Chan M, Chai P, Low AF, Ling LH, Ng TP, Richards AM, Lam CS. Iron deficiency in a multi-ethnic Asian population with and without heart failure: prevalence, clinical correlates, functional significance and prognosis. Eur J Heart Fail.2014; 16:1125–1132. doi: 10.1002/ejhf. 161.

58. Martens P, Nijst P, Verbrugge FH, Smeets K, Dupont M, Mullens W. Impact of iron deficiency on exercise capacity and outcome in heart failure with reduced, mid-range and preserved ejection fraction. Acta Cardiol. 2017;73:1–9. doi: 10.1080/000153 85.2017.1351239.

59. Cappellini MD, Comin-Colet J, de Francisco A, Dignass A, Doehner W, Lam CS, Macdougall IC, Rogler G, Camaschella C, Kadir R, Kassebaum NJ, Spahn DR, Taher AT, Musallam KM; IRON CORE Group. Iron deficiency across chronic inflammatory conditions: international expert opinion on definition, diagnosis, and management. Am J Hematol. 2017; 92:1068–1078. doi: 10.1002/ajh .24820.

60. Klip IT, Comin-Colet J, Voors AA, Ponikowski P, Enjuanes C, Banasiak W, Lok DJ, Rosentryt P, Torrens A, Polonski L, van Veldhuisen DJ, van der Meer P, Jankowska EA. Iron deficiency in chronic heart failure: an international pooled analysis. Am Heart J. 2013;165:575–582.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.01.017.

61. Anand I. Iron deficiency in heart failure. Cardiology.2014;128:317– 319. doi: 10.1159/000361040.

62. Jankowska EA, Malyszko J, Ardehali H, Koc-Zorawska E, Banasiak W, von Haehling S, Macdougall IC, Weiss G, McMurray JJ, Anker SD, Gheorghiade M, Ponikowski P. Iron status in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:827–834. doi: 10.1093/ eurheartj/ehs377.

63. Alexandrakis MG, Tsirakis G. Anemia in heart failure patients. ISRN Hematol. 2012;2012:246915. doi: 10.5402/2012/246915.

64. Weiss G, Goodnough LT. Anemia of chronic disease. N Engl J Med. 2005; 352:1011–1023. doi: 10.1056/NEJM ra041809.

65. von Haehling S, Jankowska EA, van Veldhuisen DJ, Ponikowski P, Anker SD. Iron deficiency and cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12: 659– 669. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio. 2015.109.

66. Skikne BS, Punnonen K, Caldron PH, Bennett MT, Rehu M, Gasior GH, Chamberlin JS, Sullivan LA, Bray KR, Southwick PC. Improved differential diagnosis of anemia of chronic disease and iron deficiency anemia: a prospective multicenter evaluation of soluble transferrin receptor and the sTfR/log ferritin index. Am J Hematol.2011; 86:923–927. doi: 10.1002/ajh.22108.

67. Girelli D, Nemeth E, Swinkels DW. Hepcidin in the diagnosis of iron disorders. Blood. 2016;127:2809–2813. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-12-639112.

68. Mwangi MN, Maskey S, Andang o PE, Shinali NK, Roth JM, Trijsburg L, Mwangi AM, Zuilhof H, van Lagen B, Savelkoul HF, Demir AY, Verhoef H. Diagnostic utility of zinc protoporphyrin to detect iron deficiency in Kenyan pregnant women. BMC Med. 2014; 12: 229. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0229-8.

69. Grote Beverborg N, Klip IT, Meijers WC, Voors AA, Vegter EL, van der Wal HH, Swinkels DW, van Pelt J, Mulder AB, Bulstra SK, Vellenga E, Mariani MA, de Boer RA, van Veldhuisen DJ, van der Meer P. Definition of iron deficiency based on the gold standard of bone marrow iron staining in heart failure patients. Circ Heart Fail. 2018; 11:e004519. doi: 10.1161/CIRC- HEARTFAILURE.117.004519

70. Jankowska EA, Wojtas K, Kasztura M, Mazur G, Butrym A, Kalicinska E, Rybinska I, Skiba J, von Haehling S, Doehner W, Anker SD, Banasiak W, Cleland JG, Ponikowski P. Bone marrow iron depletion is common in patients with coronary artery disease. Int J Cardiol. 2015;182:517–522. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.10.006.

71. Infusino I, Braga F, Dolci A, Panteghini M. Soluble transferrin receptor (sTfR) and sTfR/log ferritin index for the diagnosis of iron-deficiency anemia: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012; 138:642–649. doi: 10.1309/ AJCP 16NTXZLZFAIB.

72. Wish JB. Assessing iron status: beyond serum ferritin and transferrin saturation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(suppl 1):S4–S8. doi: 10.2215/CJN.014 90506.

73. van Santen S, van Dongen-Lases EC, de Vegt F, Laarakkers CM, van Riel PL, van Ede AE, Swinkels DW. Hepcidin and hemoglobin content parameters in the diagnosis of iron deficiency in rheumatoid arthritis patients with anemia. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63: 3672–3680. doi: 10.1002/art.30623.

74. Nanas JN, Matsouka C, Kara georgopoulos D, Leonti A, Tsolakis E, Drakos SG, Tsagalou EP, Maroulidis GD, Alexopoulos GP, Kanakakis JE, Anastasiou-Nana MI. Etiology of anemia in patients with advanced heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006; 48:2485–2489. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc. 2006.08.034.

75. Dale JC, Burritt MF, Zinsmeister AR. Diurnal variation of serum iron, iron-binding capacity, transferrin saturation, and ferritin levels. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;117:802–808. doi: 10.1309/ 2YT4-CMP3-KYW7-9RK1.

76. Brownl ie T, Utermohlen V, Hinton PS, Haas JD. Tissue iron deficiency without anemia impairs adaptation in endurance capacity after aerobic training in previously untrained women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:437 –443. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.3.43 7.

77. Dong F, Zhang X, Culver B, Chew HG, Kelley RO, Ren J. Dietary iron deficiency induces ventricular dilation, mitochondrial ultrastructural aberrations and cytochrome c release: involvement of nitric oxide synthase and protein tyrosine nitration. Clin Sci (Lond). 2005;109:277–286. doi: 10.1042/CS20040278.