CRAIG BARSTOW, MD, and MATTHEW RICE, MD, Womack Army Medical Center, Fort Bragg, North Carolina, JONATHAN D. McDIVITT, MD, Naval Hospital, Jacksonville, Florida

CRAIG BARSTOW, MD, is director of the Family Medicine Hospitalist Fellowship at Womack Army Medical Center, Fort Bragg, N.C.

MATTHEW RICE, MD, is a fellow in the Family Medicine Hospitalist Fellowship at Womack Army Medical Center.

JONATHAN D. McDIVITT, MD, is head of the Department of Internal Medicine and a staff cardiologist at Naval Hospital Jacksonville, Fla.

Address correspondence to Craig Barstow, MD, Womack Army Medical Center, 2817 Reilly Rd., Fort Bragg, NC 28310

(e-mail: craig.h.barstow. mil@mail.mil).

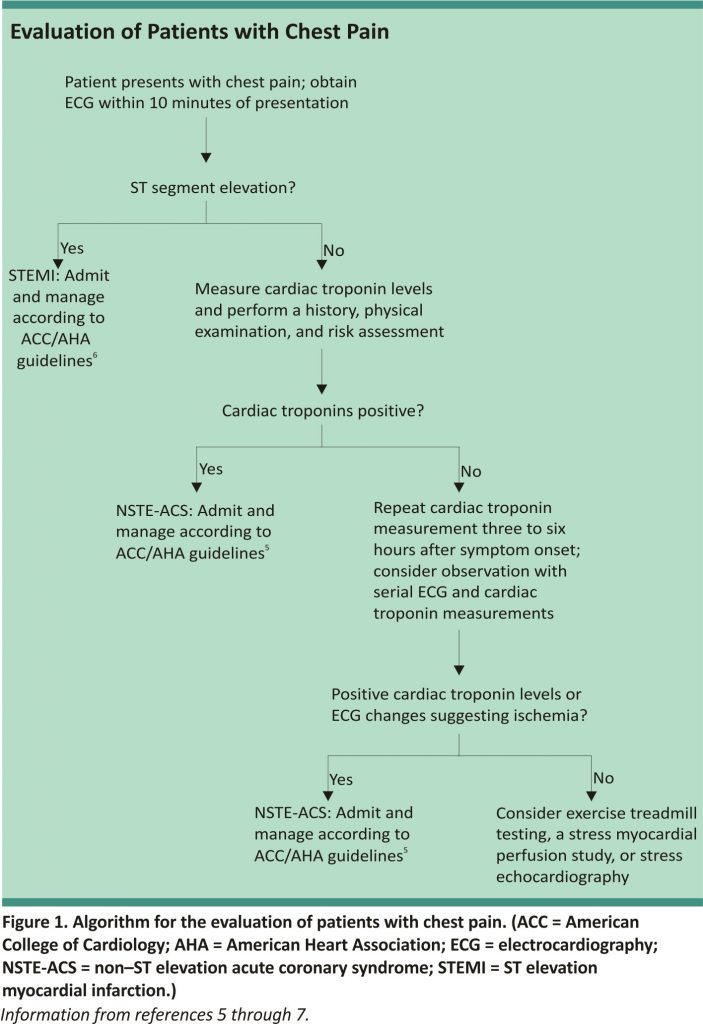

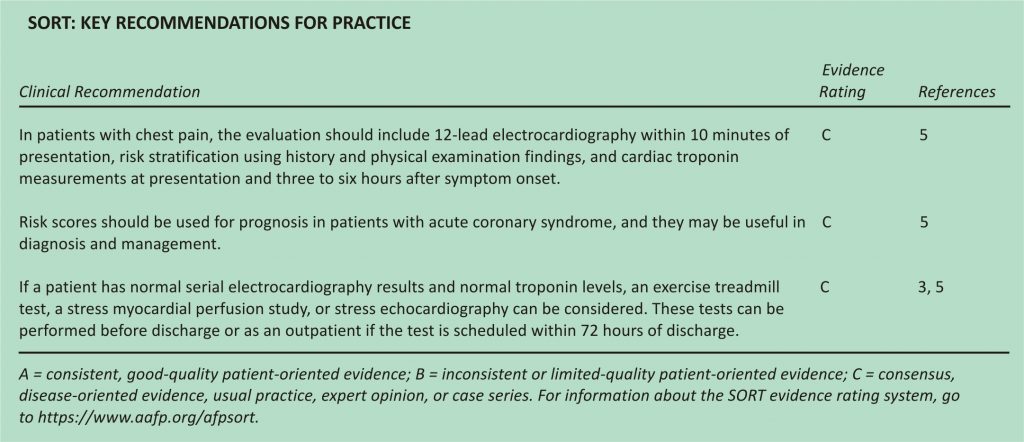

Myocardial infarction (MI), a subset of the acute coronary syndrome, is damage to the cardiac muscle as evidenced by elevated cardiac troponin levels in the setting of acute ischemia. Coronary artery disease is the leading cause of mortality in the United States. Chest pain is a common presentation in patients with MI; however, there are multiple noncardiac causes of chest pain, and the diagnosis cannot always be made based on initial presentation. The assessment of a possible MI includes evaluation of risk factors and presenting signs and symptoms, rapid electrocardiography, and serum cardiac troponin measurements. A validated risk score, such as the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction score, may also be useful. Electrocardiography should be performed within 10 minutes of presentation. ST-elevation MI is diagnosed with ST-segment elevation in two contiguous leads on electrocardiography. In the absence of ST segment elevation, non–ST-elevation ACS can be diagnosed. An elevated cardiac troponin level is required for diagnosis, and an increase or decrease of at least 20% is consistent with MI. In some patients with negative electrocardiography findings and normal cardiac biomarkers, additional testing may further reduce the likelihood of coronary artery disease. Cardiac catheterization is the standard method for diagnosing coronary artery disease, but exercise treadmill testing, a stress myocardial perfusion study, stress echocardiography, and computed tomography are noninvasive alternatives.

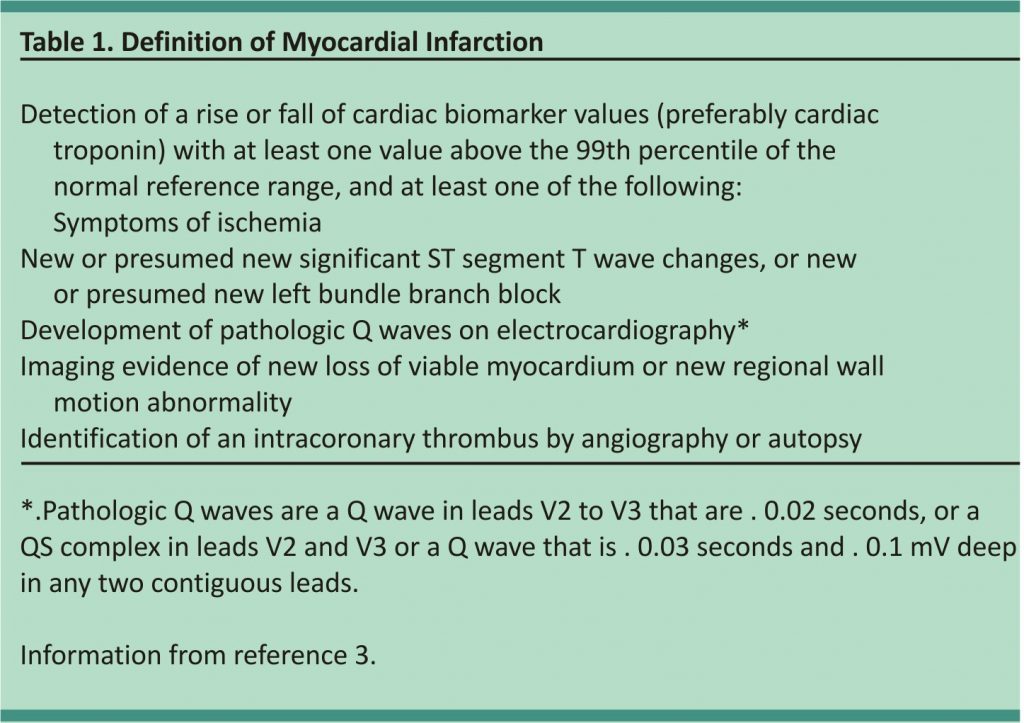

Chest pain affects 20% to 40% of the general population during their lifetime. Each year, approximately 1.5% of the population consults a primary care physician for symptoms of chest pain. The rate is even higher in the emergency department, where more than 5% of visits and up to 40% of admissions are because of chest pain.1,2 Chest pain is often the presenting symptom of myocardial infarction (MI), which is damage to the cardiac muscle caused by ischemia (Table 1).3 This can be caused by a thrombotic occlusion of a coronary vessel (type 1) or by the myocardial oxygen demand surpassing the oxygen supply (type 2).3

In the United States, coronary artery disease is the leading cause of mortality, with more than 300,000 deaths annually. Each year, more than 600,000 persons will have their first MI, and nearly 300,000 patients with known coronary artery disease will have a recurrence.4 MI is a subset of acute coronary syndrome (ACS), which is a spectrum of clinical presentations.5 ACS is divided into ST-elevation MI (STEMI) and non–ST elevation ACS, which includes unstable angina and non–ST elevation MI (NSTEMI) because the two entities are often indistinguishable at presentation. STEMI is defined as symptoms characteristic of cardiac ischemia with persistent ST-segment elevation or a new left bundle branch block on electrocardiography (ECG).6 NSTEMI is persistent symptoms with elevated cardiac troponin levels but no ST-segment elevation. Unstable angina produces symptoms suggestive of cardiac ischemia without elevated cardiac troponin levels.

Initial Approach to the Patient with Chest Pain

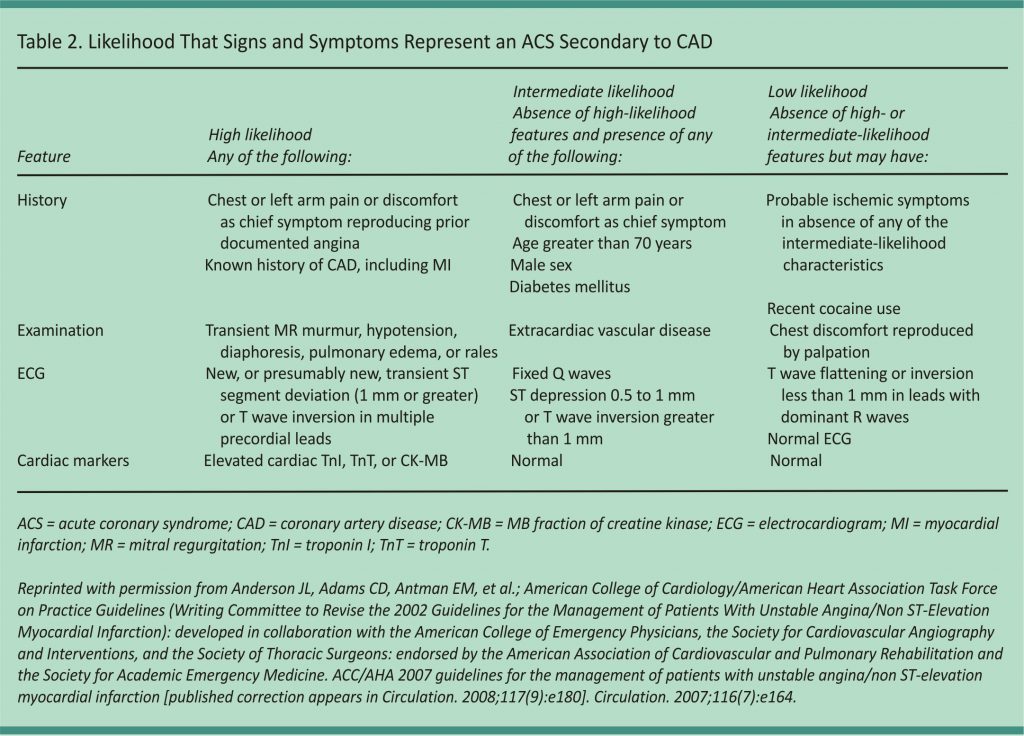

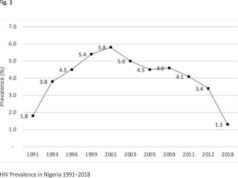

Most patients with chest pain do not have MI, and a systematic approach can usually rule it out (Figure 1).5-7 The assessment begins with a rapid 12-lead ECG within 10 minutes of presentation. If there is evidence of STEMI, the patient should be emergently referred for reperfusion therapy with primary percutaneous coronary intervention (preferred) or fibrinolytic therapy.6 If there is no evidence of STEMI, the patient’s risk of ACS should be categorized as low, intermediate, or high (Table 2).8 This is based on an assessment of risk factors, presenting signs and symptoms, and serial cardiac troponin measurements. Cardiac troponin levels should be measured at presentation and again three to six hours after symptom onset.5 Patients with elevated levels consistent with non–ST elevation ACS should be hospitalized and treated according to the American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association guidelines with an early invasive strategy (diagnostic angiography with revascularization as indicated) for higher-risk groups.5 In patients with negative cardiac troponin levels, additional confirmatory testing may be performed to further lower the risk of undiagnosed ACS; this may be done in a chest pain unit, as an inpatient, or as an outpatient.5

Clinical Diagnosis and Risk Assessment

Risk factors for MI include increasing age, male sex, chronic renal insufficiency, diabetes mellitus, known atherosclerotic disease (coronary or peripheral), and early family history of coronary artery disease (first-degree male relative with the first event before 55 years of age or first-degree female relative with the first event before 65 years of age).5 A calculator from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association estimates the 10-year risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and assists with primary prevention (http://my.americanheart.org/ cvriskcalculator).

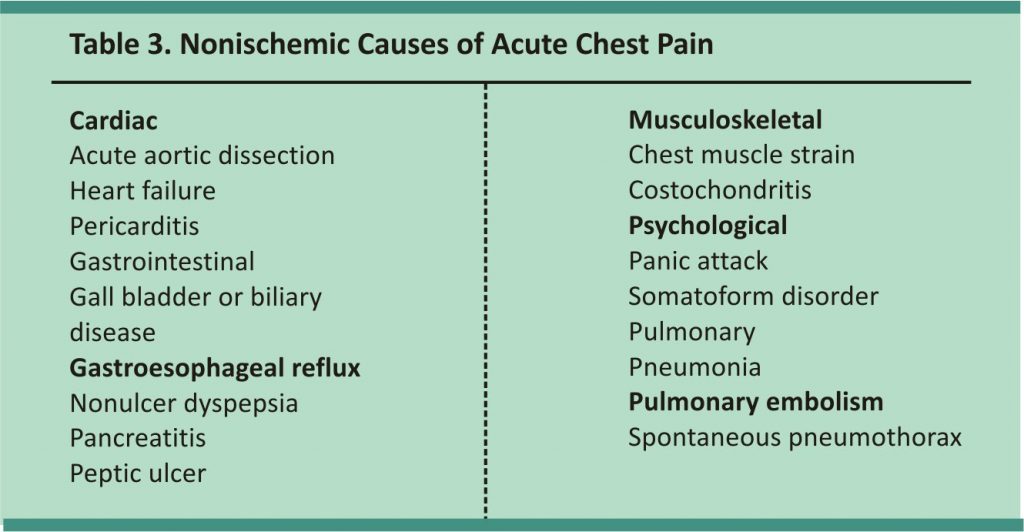

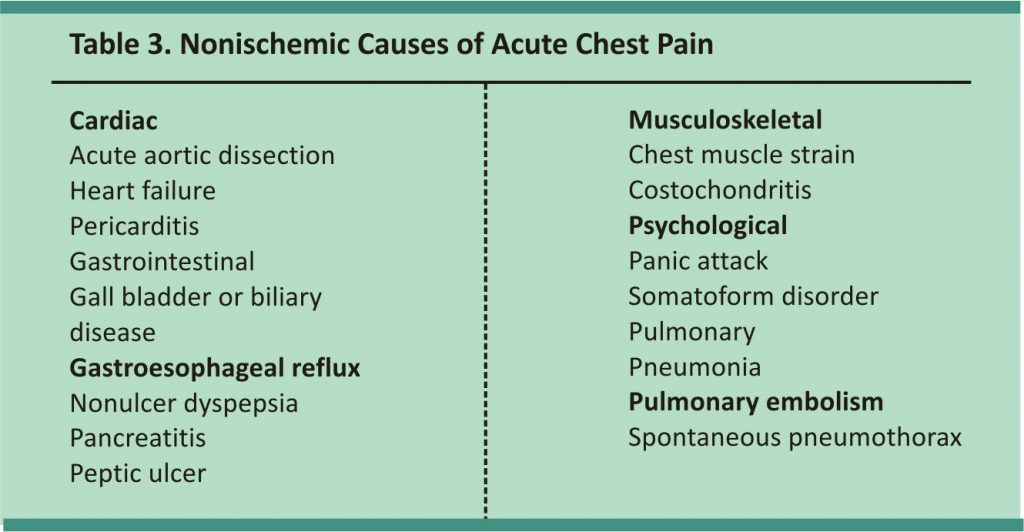

Although determining risk factors provides helpful background information, assessing symptoms is more useful during an acute presentation. Symptoms suggestive of cardiac ischemia include retrosternal chest pain (with or without radiation to either arm, the neck, or the jaw), oppressive chest pressure, abdominal pain, dyspnea, nausea, vomiting, diaphoresis, and syncope. In older persons, those with dementia or diabetes, and women, ischemic discomfort may present atypically, including epigastric discomfort, indigestion, pleuritic chest pain, and dyspnea.5 Conditions other than coronary ischemia, with cardiac or noncardiac causes (Table 3), can lead to similar symptoms and should be ruled out.

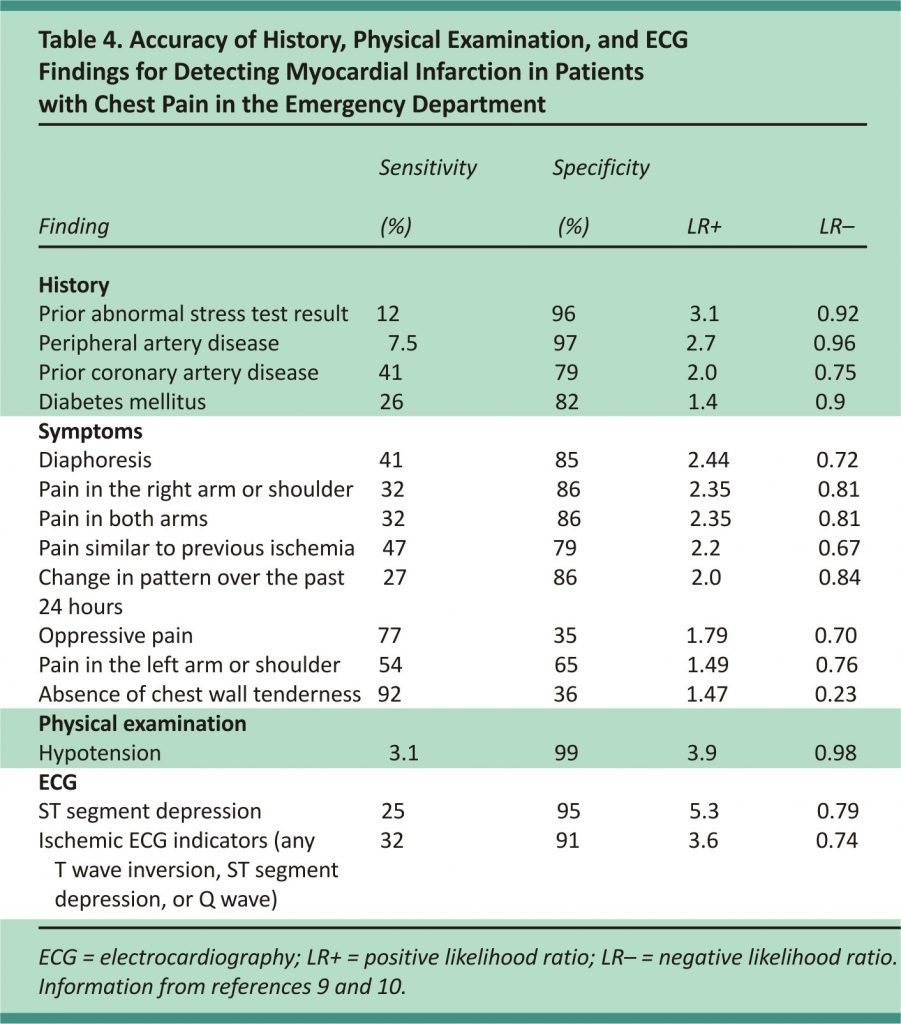

In a meta-analysis of symptoms useful in diagnosing ACS in a low-risk setting, diaphoresis was found to be the strongest predictor of MI (likelihood ratio [LR] = 2.44), and the presence of chest wall tenderness significantly reduced the possibility of MI (LR = 0.23).9 In another meta-analysis including patients presenting to the emergency department, the most useful symptoms for predicting MI were pain radiating to both arms (LR = 2.35), pain similar to a prior ischemic event (LR = 2.2), and a change in the pain within the past 24 hours (LR = 2.0).10 None of these symptoms are sufficient to exclude or confirm MI without further evaluation. Table 4 includes the accuracy of different findings in the diagnosis of chest pain in the emergency department.9,10

The physical examination is useful for determining the patient’s hemodynamic status and identifying cardiovascular instability, dysrhythmias, and volume overload. Other signs, such as heart failure or a new murmur, may suggest ischemia. The examination can also identify nonischemic cardiac causes of chest pain.5

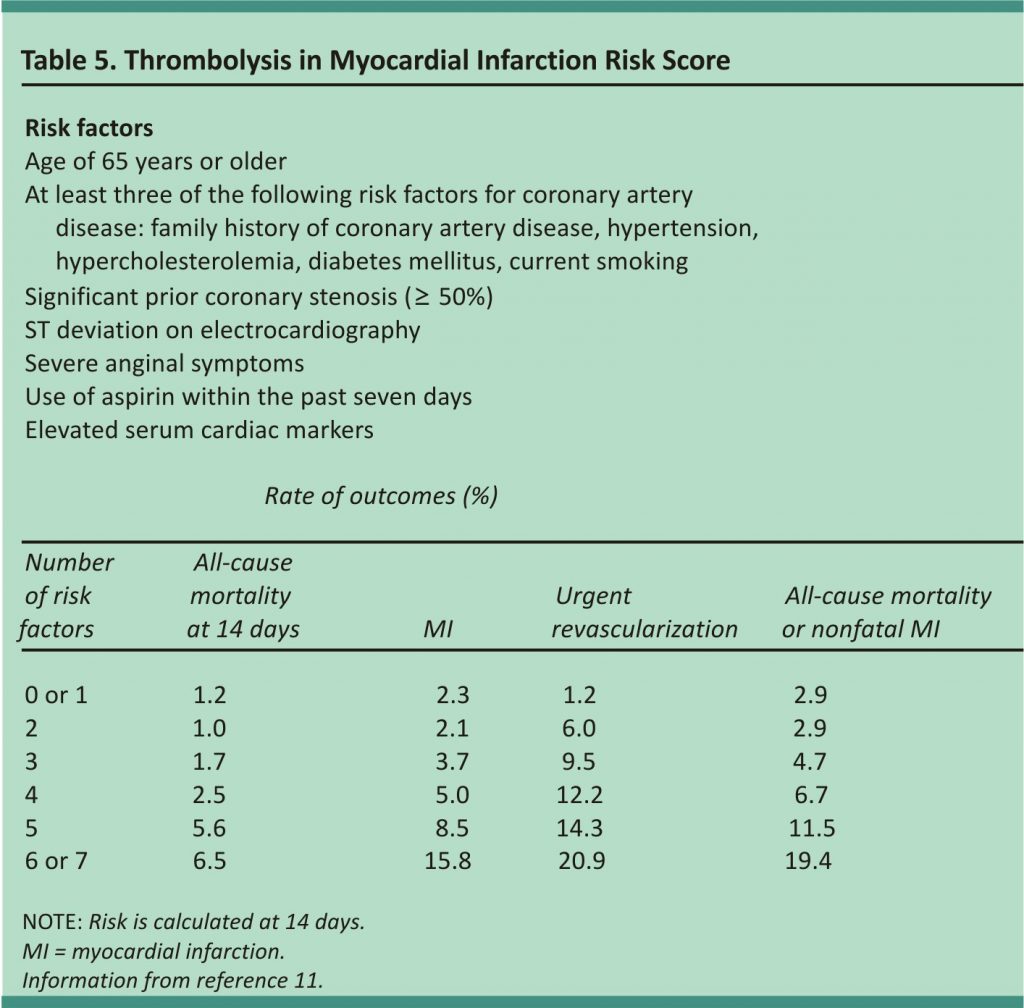

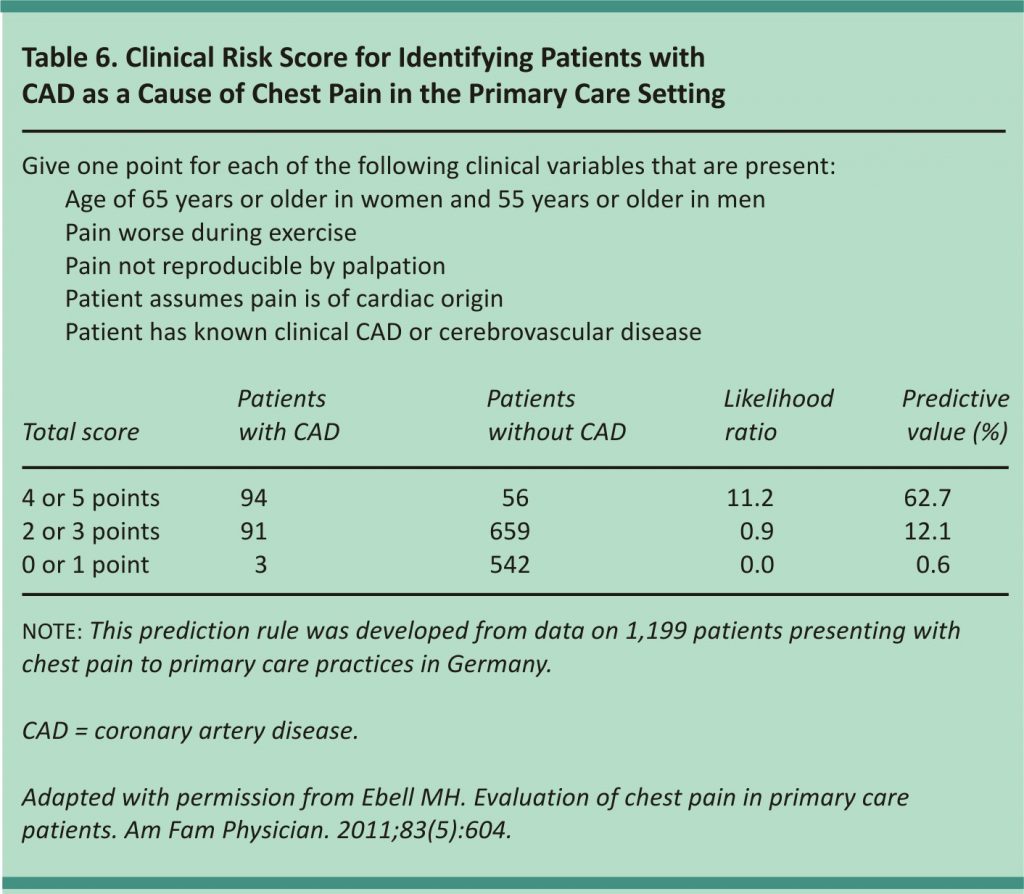

Various scoring systems have been developed to help determine the risk of ACS. The Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction score (Table 511) was initially validated as a prognostic tool for patients admitted for ACS but has been studied for use in the diagnosis of MI.10,11 A newer score (Table 612) evaluated for coronary artery disease in the primary care setting identified patients with chest pain who have a very low risk of coronary heart disease, but it did not differentiate between ACS and stable coronary artery disease.13 Both scores are useful adjuncts but do not preclude further evaluation.

Electrocardiography

Normal or near-normal ECG findings decrease the risk of MI, especially in patients with no history of coronary artery disease, but NSTEMI may occur in 1% to 6% of these patients.14 ST segment depression, symmetric T wave inversion, and Q waves are associated with an increased risk of MI.10 Abnormalities, such as ventricular hypertrophy, atrial fibrillation, pacing artefacts, and other bundle branch blocks, can conceal ischemic signs on ECG and may warrant further testing.15 Serial ECG or continuous ST segment monitoring may increase the detection of ischemic changes, especially in patients with continued pain.7,16

Criteria to diagnose STEMI include ST segment elevation of 2 mm in men and 1.5 mm in women for leads V2 and V3; 1 mm for leads V1, V4-6, I, II, III, aVL, and aVF; and 0.5 mm for leads V3R and V4R (right-sided leads) and V7-9 (posterior leads).3 Anatomically contiguous leads include any two adjacent precordial leads or any two leads in an anatomic group. ST segment elevation in leads II, III, and aVF may be evidence of a right ventricular infarct,17 and right-sided precordial or posterior leads should be obtained, especially in a patient with hypotension or jugular distention with clear lung fields.7

The presence of a new or presumed new left bundle branch block in the setting of chest pain, especially with elevated cardiac troponin levels, is diagnostic of MI and requires immediate treatment.6 A new left bundle branch block without the symptoms of ischemia should not be considered an MI equivalent.6,18

Cardiac Biomarkers

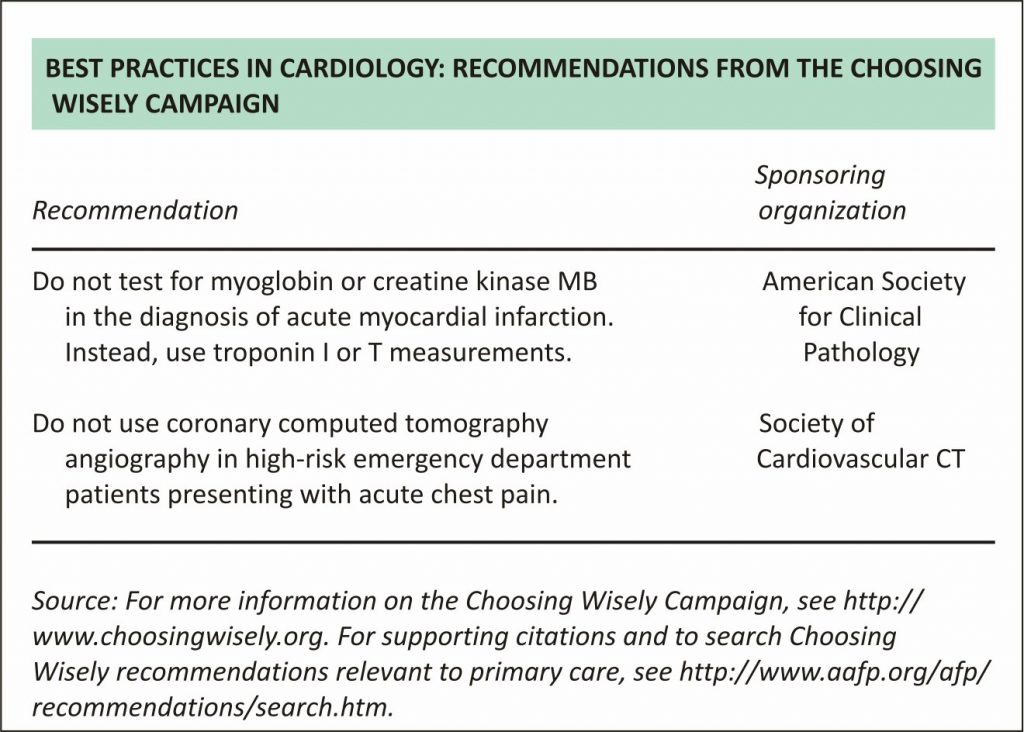

Cardiac troponins T and I are highly specific to myocardial cells and are the primary measure of myocardial injury. Measurement of other biomarkers, such as creatine kinase myocardial isoenzyme and myoglobin, is no longer recommended.5 Troponins T and I are clinically equivalent and have a sensitivity of 79% to 83% and a specificity of 93% to 95% for detecting myocardial injury.19-21 Cardiac troponin should be measured at presentation and three to six hours after onset of ischemic symptoms.5 A troponin value above the 99th percentile of the upper reference level (laboratory-specific) is required for the diagnosis of myocardial necrosis and an increase or decrease of at least 20% is required for the diagnosis of acute myocardial necrosis.3,5 Alternatively, if the initial troponin level is below the 99th percentile, a change greater than three standard deviations is considered positive for acute myocardial necrosis.5 When initial troponin results are normal but ECG changes or clinical presentation suggests a moderate or high risk of ACS, troponin levels should be measured again after six hours.5 Accelerated protocols with troponin levels measured at presentation and two hours later have been shown to have a negative predictive value of 99.7% in low-risk patients.22

New high-sensitivity troponin assays have drawn interest worldwide but are not yet approved for use in the United States. They have been incorporated into protocols that can identify a group of patients with chest pain who are at low risk of MI and 30-day cardiovascular events. These assays have higher sensitivity but lower specificity than contemporary assays and have a high negative predictive value.21,23,24 A Point-of-Care Guide on these rapid protocols appears in a previous issue of American Family Physician (http://www.aafp. org/afp/ 2016/0615/p1008.html).

Nonischemic conditions can cause cardiac troponin elevations (Table 7),25 and serial measurements may be useful to differentiate these conditions from acute MI. Patients with acute MI will have a rising or falling pattern, whereas levels will remain relatively stable with chronic conditions.3

Additional Diagnostic Testing

Chest radiography can identify a pneumothorax, pneumonia, aortic dissection, and ischemic-related left-sided heart failure. Radiography findings are rarely abnormal in patients with ACS. Likewise, computed tomography may be useful to exclude other, nonischemic causes of chest pain when clinically suspected. If available, focused bedside echocardiography can identify other cardiac causes of chest pain, such as aortic dissection, cardiac tamponade, pulmonary embolism, severe valvular disease, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Regional wall motion abnormalities on resting echocardiography may be a sign of ischemia, and the absence of these abnormalities has a high negative predictive value for ischemia but a low positive predictive value (i.e., it is primarily useful for ruling out ischemia when absent).7

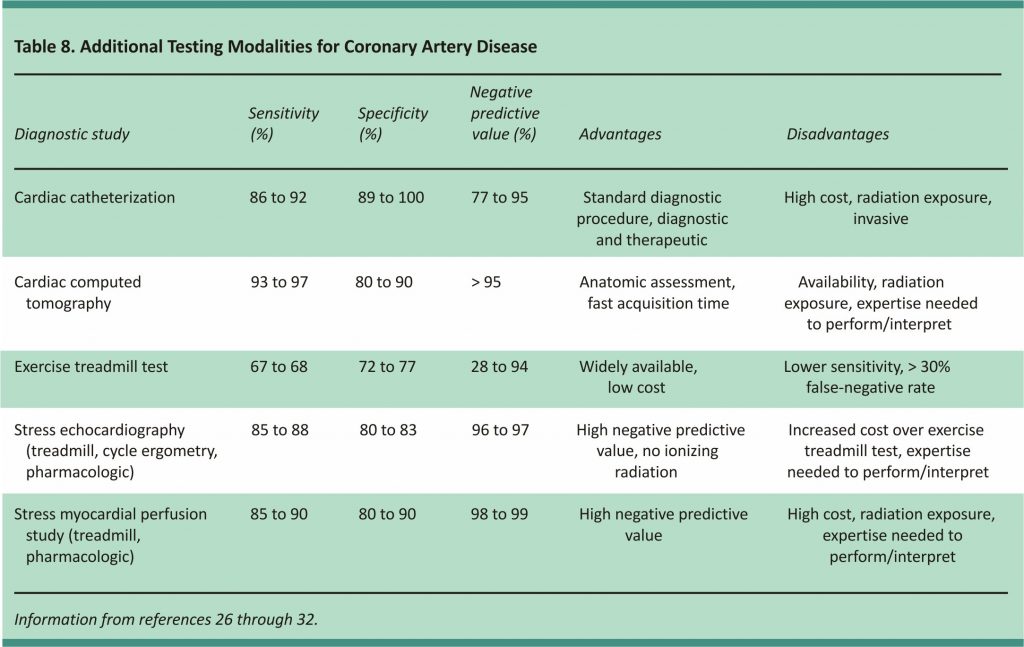

Many chest pain protocols include additional functional or anatomic testing (Table 826-32) to evaluate patients with normal or near-normal ECG results and negative cardiac troponins.5 A negative result further reduces the possibility of ischemia as the cause of chest pain.7 The standard test for diagnosing coronary artery disease is cardiac catheterization. Noninvasive testing is routinely performed before catheterization to assess the patient’s risk before an invasive procedure is performed. Patients who have normal serial ECG results and normal cardiac troponin levels can have an exercise treadmill test, a stress myocardial perfusion study, or stress echocardiography before discharge or as an outpatient if the test is scheduled within 72 hours of discharge.5

Exercise treadmill testing has been well-validated, is inexpensive, is relatively easy to conduct, and can be performed after only six to eight hours of observation.7 However, it is less sensitive than other tests, with at least a 30% false-negative rate. A stress myocardial perfusion study (single-photon emission computed tomography and positron emission tomography) and stress echocardiography diagnose ischemia by comparing resting images to post-stress images and have a higher sensitivity and specificity than ECG stress testing.27,33 These modalities are well established and validated.

Computed tomography is an emerging technology in the evaluation of suspected coronary artery disease.34,35 Coronary artery calcification is a surrogate measure of atherosclerosis and is primarily helpful when making decisions about preventive therapy in intermediate-risk patients. Computed tomography angiography evaluates the coronary arteries and has been validated in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. It has a high negative predictive value (more than 95%) for ruling out coronary artery disease. Limitations of computed tomography angiography include the need for patient heart rate control, specialized computed tomography scanners with the timing of contrast media administrations, and specially trained cardiac imaging professionals to interpret the examinations.36,37

REFERENCES

1. Nilsson S, Scheike M, Engblom D, et al. Chest pain and ischaemic heart disease in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53 (490):378-382.

2. Goodacre S, Cross E, Arnold J, Angelini K, Capewell S, Nicholl J. The health care burden of acute chest pain. Heart. 2005; 91(2):229-230.

3. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al.; Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2012;126(16):2020 -2035.

4. Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al.; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129(3):e28-e292.

5. Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al.; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; Society of Thoracic Surgeons; American Association for Clinical Chemistry. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non–ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(24):2713-2714]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(24): e139- e228.

6. O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al.; American College of Emergency Physicians; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(4):e78-e140.

7. Amsterdam EA, Kirk JD, Bluemke DA, et al.; American Heart Association Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Prevention Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Testing of low-risk patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association [published correction appears in Circulation. 2010;122(17): e500-e501]. Circulation. 2010;122(17):1756-1776.

8. Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al.; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction); developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons: endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation, and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. ACC/ AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non ST-elevation myocardial infarction [published correction appears in Circulation. 2008;117 (9):e180]. Circulation. 2007;116(7):e148-e304.

9. Bruyninckx R, Aertgeerts B, Bruyninckx P, Buntinx F. Signs and symptoms in diagnosing acute myocardial infarction and acute coronary syndrome: a diagnostic meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58(547): 105-111.

10. Fanaroff AC, Rymer JA, Goldstein SA, Simel DL, Newby LK. Does this patient with chest pain have acute coronary syndrome? The rational clinical examination systematic review. JAMA. 2015;314(18):1955-1965.

11. Antman EM, Cohen M, Bernink PJ, et al. The TIMI risk score for unstable angina/non-ST elevation MI: a method for prognostication and therapeutic decision making. JAMA. 2000;284(7):835-842.

12. Ebell MH. Evaluation of chest pain in primary care patients. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83(5):603-605.

13. Bösner S, Haasenritter J, Becker A, et al. Ruling out coronary artery disease in primary care: development and validation of a simple prediction rule. CMAJ. 2010; 182(12):1295-1300.

14. Slater DK, Hlatky MA, Mark DB, Harrell FE Jr, Pryor DB, Califf RM. Outcome in suspected acute myocardial infarction with normal or minimally abnormal admission electrocardiographic findings. Am J Cardiol. 1987;60(10):766-770.

15. Lev EI, Battler A, Behar S, et al. Frequency, characteristics, and outcome of patients hospitalized with acute coronary syndromes with undetermined electrocardiographic patterns. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91(2):224-227.

16. Wagner GS, Macfarlane P, Wellens H, et al.; American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; American College of Cardiology Foundation; Heart Rhythm Society. AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part VI: acute ischemia/infarction. Circulation. 2009; 119(10):e262-e270.

17. Kinch JW, Ryan TJ. Right ventricular infarction. N Engl J Med. 1994;330 (17):1211-1217.

18. Jain S, Ting HT, Bell M, et al. Utility of left bundle branch block as a diagnostic criterion for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107(8):1111-1116.

19. de Lemos JA. Increasingly sensitive assays for cardiac troponins: a review. JAMA. 2013;309(21):2262-2269.

20. Keller T, Zeller T, Peetz D, et al. Sensitive troponin I assay in early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(9):868-877.

21. Reichlin T, Hochholzer W, Bassetti S, et al. Early diagnosis of myocardial infarction with sensitive cardiac troponin assays. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(9):858-867.

22. Than M, Cullen L, Aldous S, et al. 2-hour accelerated diagnostic protocol to assess patients with chest pain symptoms using contemporary troponins as the only biomarker: the ADAPT trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(23):2091-2098.

23. Reichlin T, Schindler C, Drexler B, et al. One-hour rule-out and rule-in of acute myocardial infarction using high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172 (16):1211-1218.

24. Body R, Carley S, McDowell G, et al. Rapid exclusion of acute myocardial infarction in patients with undetectable troponin using a high-sensitivity assay [published correction appears in J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(12):1122]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(13):1332-1339.

25. Newby LK, Jesse RL, Babb JD, et al. ACCF 2012 expert consensus document on practical clinical considerations in the interpretation of troponin elevations: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(23):2427-2463.

26. Gibbons RJ, Balady GJ, Bricker JT, et al.; American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Committee to Update the 1997 Exercise Testing Guidelines. ACC/ AHA 2002 guideline update for exercise testing: summary article [published correction appears in J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(8) :1731]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40(8):1531-1540.

27. Metz LD, Beattie M, Hom R, et al. The prognostic value of normal exercise myocardial perfusion imaging and exercise echocardiography: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(2):227-237.

28. Gibler WB, Runyon JP, Levy RC, et al. A rapid diagnostic and treatment center for patients with chest pain in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;25(1): 1-8.

29. Mark DB, Shaw L, Harrell FE Jr, et al. Prognostic value of a treadmill exercise score in outpatients with suspected coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 1991;325 (12):849-853.

30. Janne d’Othée B, Siebert U, Cury R, Jadvar H, Dunn EJ, Hoffmann U. A systematic review on diagnostic accuracy of CT-based detection of significant coronary artery disease. Eur J Radiol. 2008;65(3):449-461.

31. Berman DS, Kang X, Nishina H, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of gated Tc-99m sestamibi stress myocardial perfusion SPECT with combined supine and prone acquisitions to detect coronary artery disease in obese and nonobese patients. J Nucl Cardiol. 2006;13(2):191-201.

32. Kern MJ. Coronary physiology revisited: practical insights from the cardiac catheterization laboratory. Circulation. 2000;101(11):1344-1351.

33. DeLorenzo A, Hachamovitch R, Kang X, et al. Prognostic value of myocardial perfusion SPECT versus exercise electrocardiography in patients with ST-segment depression on resting electrocardiography. J Nucl Cardiol. 2005;12(6):655-661.

34. Thomas DM, Divakaran S, Villines TC, et al. Management of coronary artery calcium and coronary CTA findings. Curr Cardiovasc Imaging Rep. 2015;8(6):18.

35. Cheezum MK, Hulten EA, Fischer C, Smith RM, Slim AM, Villines TC. Prognostic value of coronary CT angiography. Cardiol Clin. 2012;30(1):77-91.

36. Hulten E, Pickett C, Bittencourt MS, et al. Outcomes after coronary computed tomography angiography in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 61(8):880-892.

37. Nasir K, Michos ED, Rumberger JA, et al. Coronary artery calcification and family history of premature coronary artery disease: sibling history is more strongly associated than parental history. Circulation. 2004; 110(15):2150-2156.38.

38. Achar SA, Kundu S, Norcross WA. Diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72(1):119-126.

Credits: Barstow, C., Rice, M., & Mcdivitt, J.D. (2017). Acute Coronary Syndrome: Diagnostic Evaluation. American Family Physician, 95 (3) 170 – 177. Retrieved from https://www.aafp.org/afp/2017/0201/ p170.pdf