Ubong B. Akpan 1, Chinyere J. Akpanika 1, Udeme Asibong 2, Kazeem Arogundade 3, Adaolisa E. Nwagbata 1, Saturday Etuk 1

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Calabar Teaching Hospital, Calabar, NGA.

2Department of Family Medicine, University of Calabar Teaching Hospital, Calabar, NGA.

3Department of Public Health, Bruyere Research Institute, Ottawa, CAN.

Abstract

Background: Pregnancies complicated by threatened miscarriage (TM) may be associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. The objective of this study was to compare the differences in pregnancy outcomes between the women who experienced TM and asymptomatic controls.

Methods: This was a 10-year retrospective review. Case records of 117 women who were managed for TM from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2019, were retrieved and studied. The control group was developed from an equal number of asymptomatic clients matched for age, parity, and BMI who were receiving antenatal care (ANC) during the same period. Data on demography, clinical and ultrasound findings, treatment, and pregnancy outcomes were retrieved and analyzed.

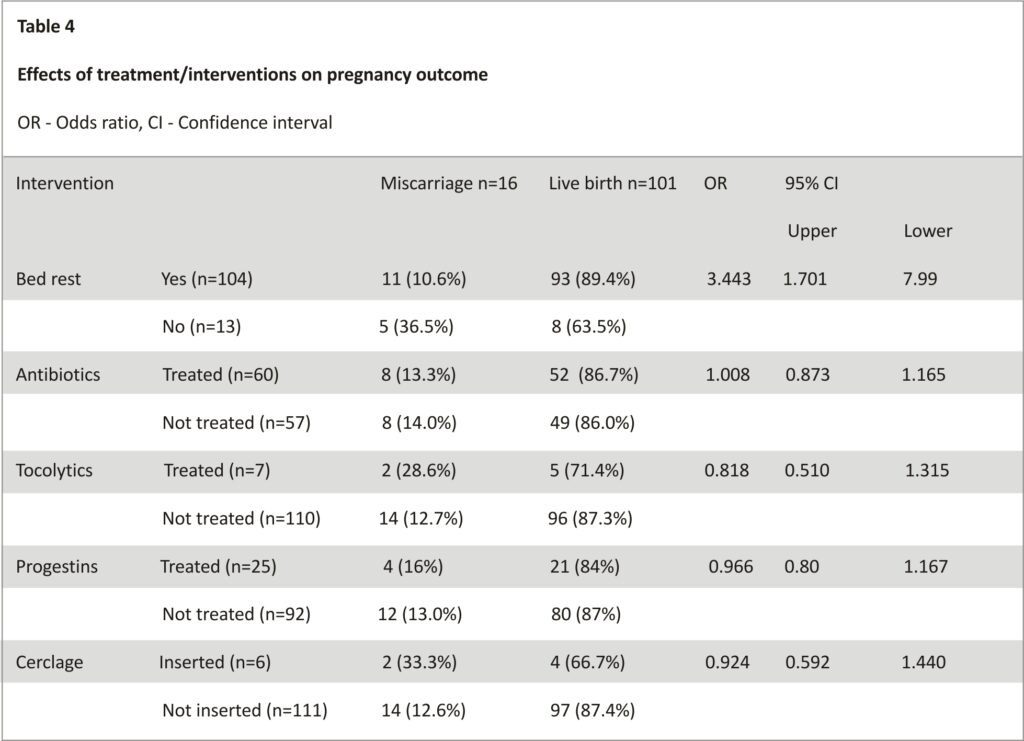

Results: Spontaneous abortion rate of 13.7% was recorded among the study group compared with 3.4% in the control (P-value [p] = 0.005, odds ratio [OR]: 4.475; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.445 – 13.827). Women with TM had higher odds for placenta previa (p = 0.049, OR: 4.77, 95% CI: 2.19 – 23.04), premature rupture of membranes (PROM) (p = 0.028, OR: 1.918, 95% CI: 1.419 – 2.592), postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) (p = 0.001, OR: 2.66, 95% CI: 20.8 – 8.94), and preterm birth (OR: 2.5, 95% CI: 1.75 – 3.65). They were also more likely to undergo cesarean section (p = 0.020, OR: 1.70, 95% CI: 1.053 – 2.964). There was no statistically significant difference in their infants’ mean birth weight (3.113 ± 0.585kg for the TM group and 3.285± 0.536kg for the control, P=0.074). Other maternal and perinatal complications were similar. Admission for bed rest significantly improved fetal survival. Women who were not admitted for bed rest had higher odds of pregnancy loss (OR: 3.443, 95% CI: 1.701-7.99). Other treatment plans did not significantly contribute to a positive outcome.

Conclusion: Threatened miscarriage is a significant threat to fetal survival and may increase the risk for operative delivery. Bed rest improves the live birth rate

Introduction

Vaginal bleeding in the first half of pregnancy is a common problem encountered in obstetrics practice and is reported to occur in about one-fifth of all pregnancies 1,2. It is one of the visible warning signs in pregnancy but oftentimes, most of such pregnancies progress to live birth with good maternal and fetal outcomes 3,4. Studies have shown that this pregnancy event is among the most common indication for admission for in-patient care during pregnancy 5,6. Threatened miscarriage is characterized by vaginal bleeding, often painless, associated with a closed cervix and ultrasonographic evidence of fetal cardiac activity occurring before 20 weeks gestational age 7.

Meta-analysis indicates that vaginal bleeding in pregnancy is associated with a two-fold increased risk of complications such as pregnancy-induced hypertension, preeclampsia, preterm rupture of membranes, spontaneous abortion, repeated and late pregnancy bleeding, placenta previa, retained placenta, and postpartum hemorrhage. About half of the bleeding episodes during pregnancy have unknown causes and it may also be difficult to predict which of such women would develop complications in the course of the gestation 8,9, although these complications are more in women with underlying medical conditions such as maternal obesity and chronic hypertension.

Threatened miscarriage is a known cause of anxiety among pregnant women who experience it and their caregivers. It also contributes to an increased financial burden in caring for pregnancies. Vaginal bleeding is a common reason for a referral from peripheral centers to the Maternal Fetal Medicine unit of our facility for specialist consultation in the first half of the pregnancy. Several interventions may be attempted to improve pregnancy outcomes in these patients including bed rest and medication such as progesterone; however, the extent to which such treatment influences pregnancy outcomes is not certain and is yet to be evaluated. Hence, this review intends to determine the influence of threatened miscarriage (TM) on maternal and perinatal outcomes and spontaneous abortion rate and also evaluate the various treatment protocols and their effects on fetal survival with the aim of suggesting an evidence-based approach to the care of such patients.

Materials & Methods

This was a retrospective cohort (case-control) study of women who met the diagnoses of threatened miscarriage and were managed in the maternity unit of the University of Calabar Teaching Hospital (UCTH), Calabar, Nigeria, between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2019. The UCTH is a second-generation Nigerian tertiary health institution situated in the south-south region of the country.

Using the patient records and register in the maternity unit of the hospital, all cases of threatened abortions were identified and the case notes were retrieved and analyzed. An equal number of asymptomatic pregnant women of similar age and parity with the same gestational ages who received antenatal care at the same period were systematically selected as control from the antenatal records. The diagnosis of threatened miscarriage was made by clinical and sonographic findings. The diagnostic criteria were based on a documented history of vaginal bleeding with a closed cervix before the gestational age of 20 weeks and ultrasound documented evidence of fetal heart activity at the time of presentation in the hospital 7,10.

Women with the following medical and pregnancy complications were excluded. They include diabetes mellitus, chronic hypertension, chronic renal disease, cardiac disease in pregnancy, known thrombophilia, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, prior diagnosis of cervical incompetence, ultrasound evidence of fetal congenital anomaly, uterine anomaly, and uterine pathologies such as fibroids, prior myomectomy, or cervical amputations. The outcome measures were pregnancy complications such as spontaneous abortion, antepartum hemorrhage (placenta abruption and placenta previa), preeclampsia/eclampsia, pregnancy-induced hypertension, preterm labor and preterm birth, preterm pre-labor rupture of membranes (PPROM), mode of delivery, retained placenta, postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), low birth weight (<2.5Kg), birth asphyxia, neonatal ICU (NICU) admission, perinatal death, and neonatal sepsis.

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0 (Released 2016; IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, United States). Descriptive data were presented as frequencies and proportions. Logistic regression was computed to assess the relationship between dependent variables (pregnancy complications) and sub-groups (Independent variables). The statistically significant differences in mean BMI and the mean infant birth weights in the two groups were accessed using Z-test. The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Formal approval was obtained from the UCTH Research Ethics Committee (protocol number UCTH/ HREC/33/ 90) before the commencement of the study. Information obtained from patients’ records was handled confidentially.

Results

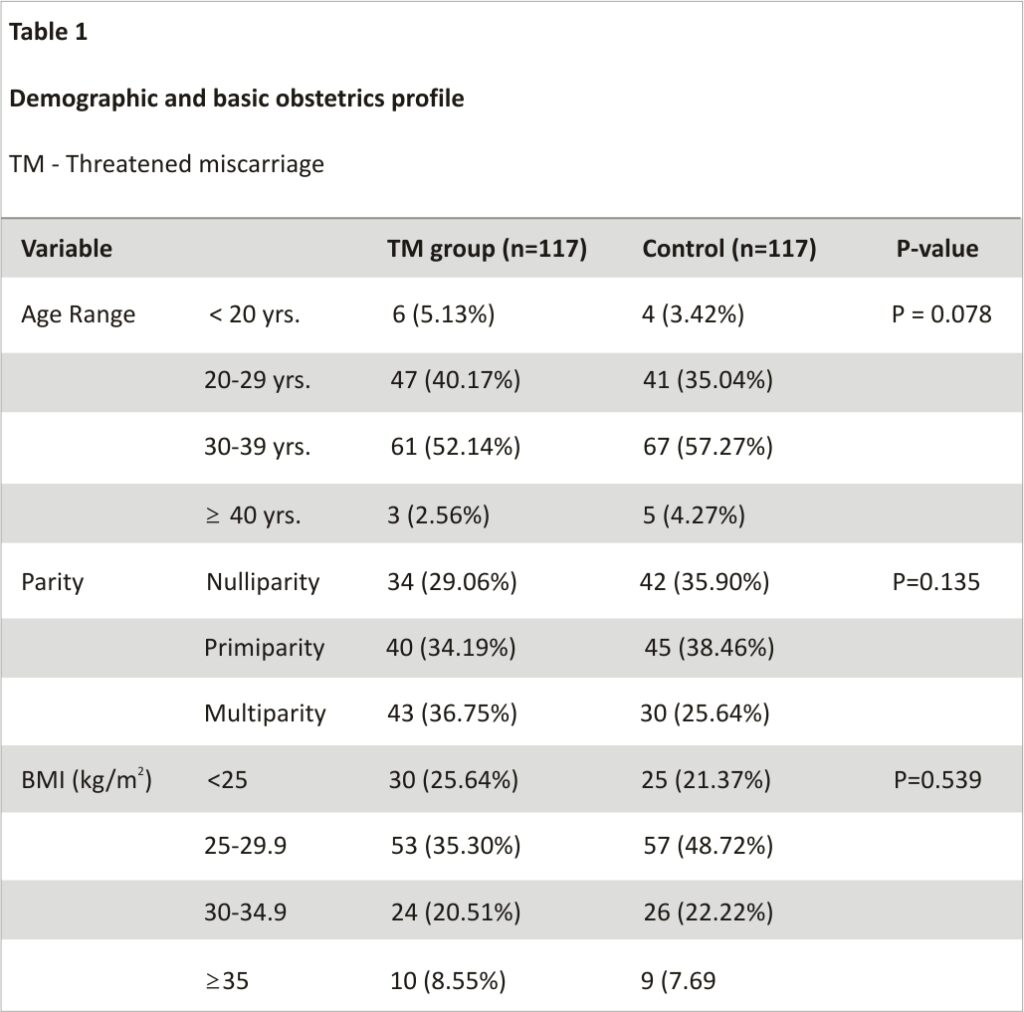

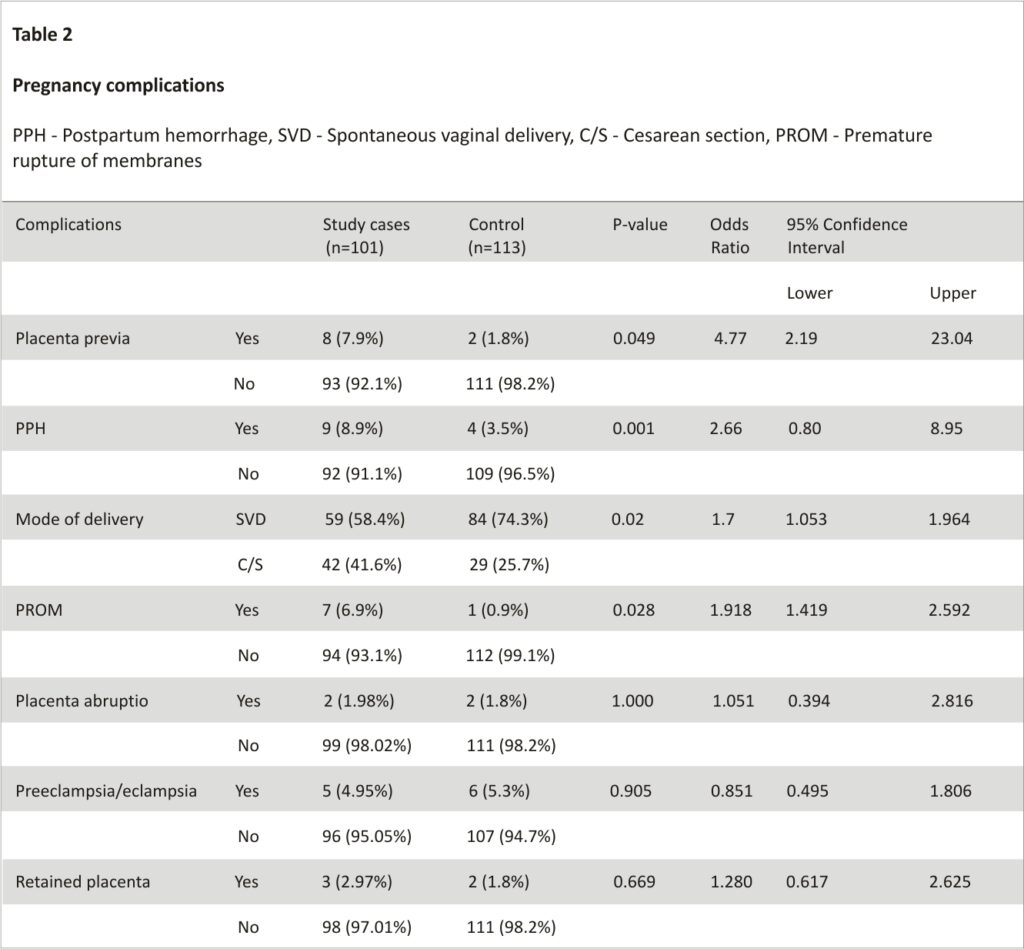

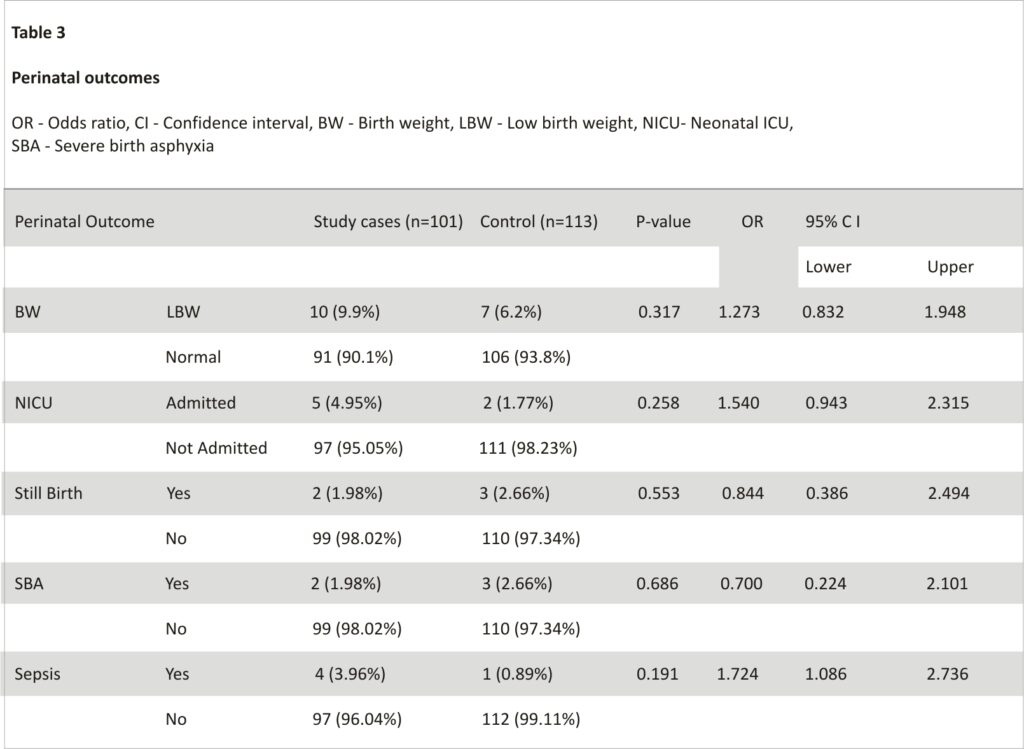

From available records, a total of 117 cases managed within the period under review met the diagnostic/inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis. An equal number of matched controls was also included in the final analysis. The mean BMI of the women was similar: 28.160 ± 5.082kg/m2 for the TM arm and 27.942± 4.418kg/m2 for the control arm (P = 0.798). Table 1 shows the demographic profile of the two groups of women. Among the women who experienced TM, 16 (13.7%), lost the pregnancy before fetal viability (spontaneous miscarriage) while 4 (3.4%) among the control had miscarriages. The difference was statistically significant (P = 0.005, OR: 4.475; 95% CI: 1.445 – 13.827). Among the women whose pregnancies progressed to fetal viability, there was a higher incidence of preterm delivery (before 37 weeks of gestation) among the TM group compared to the control, 10.9% versus 4.4%, (OR: 2.5; 95% CI: 1.75 – 3.65). In considering the mode of delivery, the study found that TM was associated with higher odds for cesarean delivery compared to the control (42.6% versus 25.7 %, OR: 1.7; 95% CI: 1.05 -2.96, P=0.02). Table 2 compares the incidences of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Women with TM had a statistically significantly higher incidence of placenta previa compared with the control (7.9% versus 1.8%; OR: 4.77; 95% CI: 2.19 – 23.04; P = 0.049). There were also statistically significantly increased odds for PPH and premature rupture of membranes (PROM). There was also no statistical difference in their mean birth weights: 3.113 ± 0.585kg for the TM group and 3.285 ± 0.536kg for the control (P=0.074). Table 3 summarizes other perinatal outcomes. In terms of intervention to improve pregnancy outcomes, the study revealed that admission to the ward for in-patient care was a departmental policy routinely practiced. However, 11 of the women with TM declined admission and were managed as outpatient care. The main reason for in-patient care was bed rest. Analysis showed that five out of thirteen (36.5%) of the women who were managed on an outpatient basis miscarried their pregnancy compared to 11 out of 104 (10.6%) who had bed rest in the hospital until the bleeding stopped. (OR: 3.443, 95% CI: 1.70 – 7.99). Apart from bed rest, other interventions recorded include the administration of tocolytic drugs such as beta-agonists, antibiotics, progesterone supplements, sedatives, and cervical cerclage placement. The details of the interventions are shown in Table 4.

Discussion

In this review, we found that vaginal bleeding in early pregnancy was a common pregnancy complication and the most common indication for admission during the first and second trimesters of pregnancy in this center. However, we included only cases that met the diagnostic criteria in the final analysis. Women who were managed and discharged without ultrasound evidence of fetal cardiac activity at the time of the bleeding event were excluded, which explains the relatively few cases analyzed within the period under review. The incidence of spontaneous miscarriage of 13.7% among women with TM compared to 3.4% in asymptomatic controls in this study indicates that TM is a warning sign for possible unwanted occurrence. This rate among TM pregnancies is similar to findings from other studies 10-12. Threatened miscarriage is therefore a major risk factor for pregnancy loss before fetal viability

Apart from the increased risk of spontaneous miscarriage, TM was associated with relatively increased odds of placenta previa, PROM, and preterm birth compared with the asymptomatic women. This is in keeping with other studies 13-15. Clinically, the low-lying placenta often presents as a warning bleed. Ultrasound imaging should be considered to ascertain placental location in women with a history of TM in the index pregnancy. Placenta previa is a major risk factor for PPH 16. The incidence of other pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia and placenta abruption was similar in the two groups.

The pathogenesis of TM and the adverse effects on pregnancy outcomes is not well understood. Abnormal placentation and implantation may result in first-trimester bleeding which if not resolved can progress to spontaneous abortion 17. The molecular study has shown a significant increase in placental markers of oxidative stress in TM pregnancies 18. Mal-expression of placental antioxidant enzymes and disruption in the balance of production of reactive oxygen radicals and the natural antioxidant defenses as well as endothelial damage leading to thrombi formation may negatively affect placental development and pregnancy outcome 19, hence the higher incidences of pregnancy complications.

The increased cesarean delivery rate among patients with TM may have been affected by the higher incidences of placenta praevia and preterm birth, which are common indications for cesarean section. There were no significant differences in perinatal complication rates in the two groups of women. This is in keeping with other reports 20,21.

The treatment plans for women with TM were evaluated and the possible impact on their pregnancy outcomes was assessed. The major interventions identified were bed rest, prophylactic antibiotics, progesterone therapy, cervical cerclage insertion, and administration of tocolytic drugs. However, our analysis suggests that only bed rest was effective in preventing pregnancy loss among women with TM. In a systematic review, prophylactic antibiotics did not reduce the risk of preterm rupture of membranes or preterm labor 22. The effect of antibiotics was only observed in patients who had evidence of vaginal bacterial infection. Also, there was no difference in birth weight or neonatal sepsis similar to our findings 22.

Also, the use of tocolytics like magnesium sulfate and beta-2 adrenergic receptor agonists in women with TM in this study did not significantly prevent pregnancy loss. In some other studies, while magnesium treatment in women with low serum magnesium levels with preterm uterine contractions was beneficial, its use in patients with threatened miscarriage with absent uterine contractions did not improve pregnancy outcomes 23,24. Furthermore, the success of emergency cervical cerclage insertion in preventing pregnancy loss in patients with TM is controversial. When prophylactic cerclage placement is offered to patients with ultrasound evidence of short or insufficient cervix, pregnancy outcome may improve, but its use in women with TM confers no significant benefit 25,26. Similarly, there have been conflicting reports on the effectiveness of progesterone in the treatment of TM. A recent Cochrane review concluded that the available evidence suggests that progestogens probably make little or no difference in the live birth rate in women with TM 27.

Study limitations

The main limitation of this study is its retrospective nature. Sometimes vital information is missed in documentation; hence, the analysis was limited to cases that met diagnostic study criteria and adequate information concerning diagnosis, treatment, and outcome. Case notes with improper documentation were excluded from the final analysis.

A set of cofounders was controlled using regression analysis and the independent determinants/factors are presented. Wherever cofounders were encountered, path analysis was done to rule out the effect.

Conclusions

At present, it is difficult to accurately predict which pregnancy with early pregnancy bleeding will eventually lead to miscarriage. The inability to accurately predict which pregnancy with threatened miscarriage will survive or end in spontaneous miscarriage may lead to unnecessary and potentially harmful or wasteful intervention. We recommend that women with TM should be offered bed rest in the hospital or if declined they should be counseled on modified bed rest at home. Psychological counseling and fetal surveillance should be offered to improve outcomes. The high probability of operative delivery should be discussed with the patients.

Additional Information

Disclosures

Human subjects: Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study. The University of Calabar Teaching Hospital (UCTH) Research Ethics Committee issued approval UCTH/ HREC/33/90.

Animal subjects: All authors have confirmed that this study did not involve animal subjects or tissue.

Conflicts of interest: In compliance with the ICMJE uniform disclosure form, all authors declare the following

Payment/services info: All authors have declared that no financial support was received from any organization for the submitted work.

Financial relationships: All authors have declared that they have no financial relationships at present or

within the previous three years with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work.

Other relationships: All authors have declared that there are no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the contribution of the nursing staff of antenatal and gynecological wards, theatre staff, staff of the record department, and the Department of Community Health of the University of Calabar Teaching Hospital, Calabar, Nigeria, towards the success of this work.

References

1. Paspulati RM, Bhatt S, Nour SG: Sonographic evaluation of first-trimester bleeding. Radiol Clin North Am. 2004, 42:297-314.

2. Chen BA, Creinin MD: Contemporary management of early pregnancy failure. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2007, 50:67-88. 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3 1802f1233

3. Yang J, Savitz DA: The effect of vaginal bleeding during pregnancy on preterm and small-for-gestational-age births: US National Maternal and Infant Health Survey, 1988. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2001, 15:34-9. 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.00318.x

4. Lykke JA, Paidas MJ, Langhoff-Roos J: Recurring complications in a second pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009, 113:1217-24.10.1097/AOG.0b013e 3181a66f2d

5. Yang J, Hartmann KE, Savitz DA, Herring AH, Dole N, Olshan AF, Thorp JM Jr: Vaginal bleeding during pregnancy and preterm birth. Am J Epidemiol. 2004, 160:118-25. 10.1093/aje/kwh 180

6. Saraswat L, Bhattacharya S, Maheshwari A, Bhattacharya S: Maternal and perinatal outcome in women with threatened miscarriage in the first trimester: a systematic review. BJOG. 2010, 117:245-57. 10.1111/j.1471-0528. 2009.02427.x

7. Calleja-Agius J, Schembri-Wismayer P, Calleja N, Brincat M, Spiteri D: Obstetric outcome and cytokine levels in threatened miscarriage. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2011, 27:121-7.10.3109/09513590. 2010.487614

8. Mulik V, Bethel J, Bhal K: A retrospective population-based study of primigravid women on the potential effect of threatened miscarriage on obstetric outcome. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004, 24:249-53.10.1080/014436104100 01660724

9. Ahmed SR, El-Sammani Mel-K, Al-Sheeha MA, Aitallah AS, Jabin Khan F, Ahmed SR: Pregnancy outcome in women with threatened miscarriage: a year study. Mater Sociomed. 2012, 24:26-8. 10.5455/msm.2012.24.26-28

10. Şükür YE, Göç G, Köse O, et al.: The effects of subchorionic hematoma on pregnancy outcome in patients with threatened abortion. J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc. 2014, 15:239-42. 10.5152/jtgga.2014.14170

11. Sivasane DS, Daver RG: Study of pregnancy outcome of threatened abortion and its correlation with risk factor in a tertiary care hospital of Mumbai, India. Int J Rerprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2018, 7:4598-603.10.18203/2320-1770.ijrcog20 184514

12. Agarwal S, Khoiwal S, Jayant K, Agarwal R: Predicting adverse maternal and perinatal outcome after threatened miscarriage. Open J Obstet Gynecol. 2014, 4:1-7.10.4236/ojog.2014. 41001

13. Dadkhah F, Kashanian M, Eliasi G: A comparison between the pregnancy outcome in women both with or without threatened abortion. Early Hum Dev. 2010, 86:193-6. 10.1016/ j.earlhumdev. 2010.02.005

14. Petriglia G, Palaia I, Musella A, et al.: Threatened abortion and late-pregnancy complication: a case-control study and review of the literature. Minerva Ginecol. 2015, 67:491-7.

15. Elovitz MA, Baron J, Phillippe M: The role of thrombin in preterm parturition. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001,185:1059-63.10.1067/mob. 2001.117638

16. Redman CW, Sargent IL: Pre-eclampsia, the placenta, and the maternal systemic inflammatory response–a review. Placenta. 2003, 24 Suppl A: S21-7. 10.1053/plac.2002.0930

17. Norwitz ER: Defective implantation and placentation: laying the blueprint for pregnancy complications. Reprod Biomed Online. 2006, 13:591-9. 10.1016/s1472-6483 (10)60649-9

18. Lockwood CJ, Krikun G, Rahman M, Caze R, Buchwalder L, Schatz F: The role of decidualization in regulating endometrial hemostasis during the menstrual cycle, gestation, and in pathological states. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2007, 33:111-7. 10.1055/s-2006-958469

19. Johns J: The pathophysiology of threatened miscarriage and its effect on pregnancy outcome. UCL (University College London), 2007.

20. De Sutter P, Bontinck J, Schutysers V, Van der Elst J, Gerris J, Dhont M: First-trimester bleeding and pregnancy outcome in singletons after assisted reproduction. Hum Reprod. 2006, 21:1907-11. 10.1093/ humrep/del054

21. Outcome of pregnancies threatening to miscarry predicted accurately for the first time. (2011). Accessed: August 15, 2022: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/07/110705071536.htm.

22. Thinkhamrop J, Hofmeyr GJ, Adetoro O, Lumbiganon P, Ota E: Antibiotic prophylaxis during the second and third trimester to reduce adverse pregnancy outcomes and morbidity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015, 1:CD002250.10.1002/14651858. CD002250.pub2

23. Lurie S, Gur D, Sadan O, Glezerman M: Relationship between uterine contractions and serum magnesium levels in patients treated for threatened preterm labour with intravenous magnesium sulphate. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004, 24:247-8. 10.1080/01443610410001660715

24. Kawagoe Y, Sameshima H, Ikenoue T, Yasuhi I, Kawarabayashi T: Magnesium sulfate as a second-line tocolytic agent for preterm labor: a randomized controlled trial in Kyushu Island. J Pregnancy.2011,2011:965060.10. 1155/ 2011/965060

25. Yilanlioglu NC, Semiz A, Arisoy R: The efficiency of emergency cerclage for the prevention of pregnancy losses and preterm labour. Perinat J. 2019, 27:1-5. 10.2399/prn.19.0271001

CREDITS: Akpan UB, Akpanika CJ, Asibong U, Arogundade K, Nwagbata AE, Etuk S. The Influence of Threatened Miscarriage on Pregnancy Outcomes: A Retrospective Cohort Study in a Nigerian Tertiary Hospital. Cureus. 2022 Nov 21;14(11): e31734. doi: 10.7759/cureus.31734. PMID: 36569728; PMCID: PMC9771571.